Bayou Segnette State Park, Westwego, Louisiana

When the time came for her to give birth, there were twin boys in her womb. As she was giving birth, one of them put out his hand; so the midwife took a scarlet thread and tied it on his wrist and said, “This one came out first.” But when he drew back his hand, his brother came out, and she said, “So this is how you have broken out!” And he was named Perez (means breaking out). Then his brother, who had the scarlet thread on his wrist, came out and he was given the name Zerah (means scarlet or brightness). ~ Genesis 38:27-30 Does this sound familiar? Twins (Esau and Jacob) were also born to Isaac and Rebekah, Judah’s grandparents. And the second born became the blessed one – the one to carry the ancestral line of Christ. As I was looking into the issues with Judah and his deviation from his roots, I ran across several commentators who said that the propensity for intermarriage with foreign peoples many Israelites had, is the reason the Israelites had to end up enslaved to Egypt; in order to preserve the race, and also to have the opportunity to grow into a large people group. Something to consider. When God allows bad things to happen, it’s always for a greater good, whether we see it or not.

artist unknown

We finally got the kayak back out! It’s been a long, long time!

Where, you ask?

Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve.

Still can’t figure out why our Park Service named a National Park after a pirate. Yes, I know he helped with the Battle of New Orleans. Quite a bit, even. But surely there were Americans who fought in the same battle and deserved to have a Park named after them?

Their large brochure carries the following small bit of information on him:

Before the Battle of New Orleans, Jean Lafitte commanded a large confederation of smugglers and privateers based in Barataria Bay. Tough long hounded by American authorities for smuggling slaves and goods, he joined forces with Jackson in the battle, providing men, artillery and information. Pardoned for his service, he slipped form the pages of history and lingers only in delta legend.

They also shared this bit of information about the culture down here:

Creoles and Cajuns – names romanticized, stereotyped, and misunderstood. Visitors are deluged with the words, all too often used to sell something rather than convey meaning about a people and their culture. Who are Creoles and Cajuns, and what do the names mean?

Today various groups in Louisiana describe themselves as Creole – often claiming exclusive rights to the term. All have legitimate ties to that heritage. The distinction dates to the early 1800s, when Louisiana ceased to be a European colony and became a possession of the United States. Creole originally meant “born in the New World.” Whether people were of French, Spanish, African, or German heritage, it meant “us” – French-speaking and native born. “They” were Americans or European immigrants arriving in droves at the port of New Orleans, speaking not French but English or their native tongues. They were outsiders bent on changing the Creole way of life.

Times change, meanings blur, and people’s sense of themselves evolves. But “Creole” retains its old meaning as an adjective describing the food, music, and customs of those areas of Louisiana settled during French colonial times. In a sense, despite the overwhelming Americanization of Louisiana, the original Creoles won. Visitors come to experience Creole, to experience what sets this place apart: Mardi Gras and red beans, jazz and Joie de vivre. Whoever came here – English, African, Irish, Italian, Chinese, Filipino, Croatian, Honduran, or Vietnamese – contributed to Creole culture and in turn were shaped by it.

From their arrival in the late 1700s the Acadians, or “Cajuns,” were a people apart. Mostly small farmers and craftspeople, they settled in the bayou country, where their isolation was compounded by their distinctive dialect and their fierce loyalty to family and place. Urbane New Orleanians saw them as a quaint and rustic, subjects of humor. Driven by hard times to seek other livelihoods, Cajuns pioneered new ways to live off the bounty of the delta landscape. In this they were joined by other groups who helped shape the culture we now know as Cajun. No longer isolated, their culture is admired worldwide – even in New Orleans.

Since the National Park doesn’t seem to have much information on its namesake, I turned to Britannica.com, and found this:

Jean Laffite, Laffite also spelled Lafitte, (born 1780?, France—died 1825?), privateer and smuggler who interrupted his illicit adventures to fight heroically for the United States in defense of New Orleans in the War of 1812.

Little is known of Laffite’s early life, but by 1809 he and his brother Pierre apparently had established in New Orleans a blacksmith shop that reportedly served as a depot for smuggled goods and slaves brought ashore by a band of privateers. From 1810 to 1814 this group probably formed the nucleus for Laffite’s illicit colony on the secluded islands of Barataria Bay south of the city. Holding privateer commissions from the republic of Cartagena (in modern Colombia), Laffite’s group preyed on Spanish commerce, illegally disposing of its plunder through merchant connections on the mainland.

Because Barataria Bay was an important approach to New Orleans, the British during the War of 1812 offered Laffite $30,000 and a captaincy in the Royal Navy for his allegiance. Laffite pretended to cooperate, then warned Louisiana officials of New Orleans’s peril. Instead of believing him, Gov. W.C.C. Claiborne summoned the U.S. Army and Navy to wipe out the colony. Some of Laffite’s ships were captured, but his business was not destroyed. Still protesting his loyalty to the United States, Laffite next offered aid to the hard-pressed forces of Gen. Andrew Jackson in defense of New Orleans if he and his men could be granted a full pardon. Jackson accepted, and in the Battle of New Orleans (December 1814–January 1815) the Baratarians, as Laffite and his men came to be known, fought with distinction. Jackson personally commended Laffite as “one of the ablest men” of the battle, and Pres. James Madison issued a public proclamation of pardon for the group.

Nevertheless, after the war the pirate chief returned to his old ways, and in 1817, with nearly 1,000 followers, he organized a commune called Campeche on the island site of the future city of Galveston, Texas, where he served briefly as governor in 1819. From this depot he continued his privateering against the Spanish, and his men were commonly acknowledged as pirates. When several of his lieutenants attacked U.S. ships in 1820, official pressure was brought to bear on the operation. As a consequence, the following year Laffite suddenly picked a crew to man his favorite vessel, The Pride, burned the town, and sailed away—apparently continuing his depredations along the coast of Spanish America (the Spanish Main) for several more years.

The world loves a good pirate story; (just look at Capt’n Jack Sparrow!) even the really bad boys like Blackbeard and Henry Morgan. Hollywood grabbed Lafitte’s story, took a bunch of liberties (including oftentimes making him in charge of Andrew Jackson) and drew as much out of it as possible, providing hours and hours of entertainment.

Fortunately, we didn’t come here looking for history because we wouldn’t have found it. We came looking for the bayou, and a place to kayak amongst the slow-moving waters, cedar trees, wading birds and maybe – just maybe – an alligator or two. It’s kinda cold for them to be out, so we didn’t expect to see them, butcha never know!

We began with a short trail between two man-made canals, but except for the narrow trail, through undeveloped terrain, that’s all the hiking we ended up doing today.

Isn’t it beautiful?!?

We spotted deer crossing the waters, one of which seemed like he wasn’t going to make it out, it was even snorting like it was trying to blow water out of its nose! Whew! So glad when it was able to climb out!

Before it got to the other side, it’s entire body disappeared!

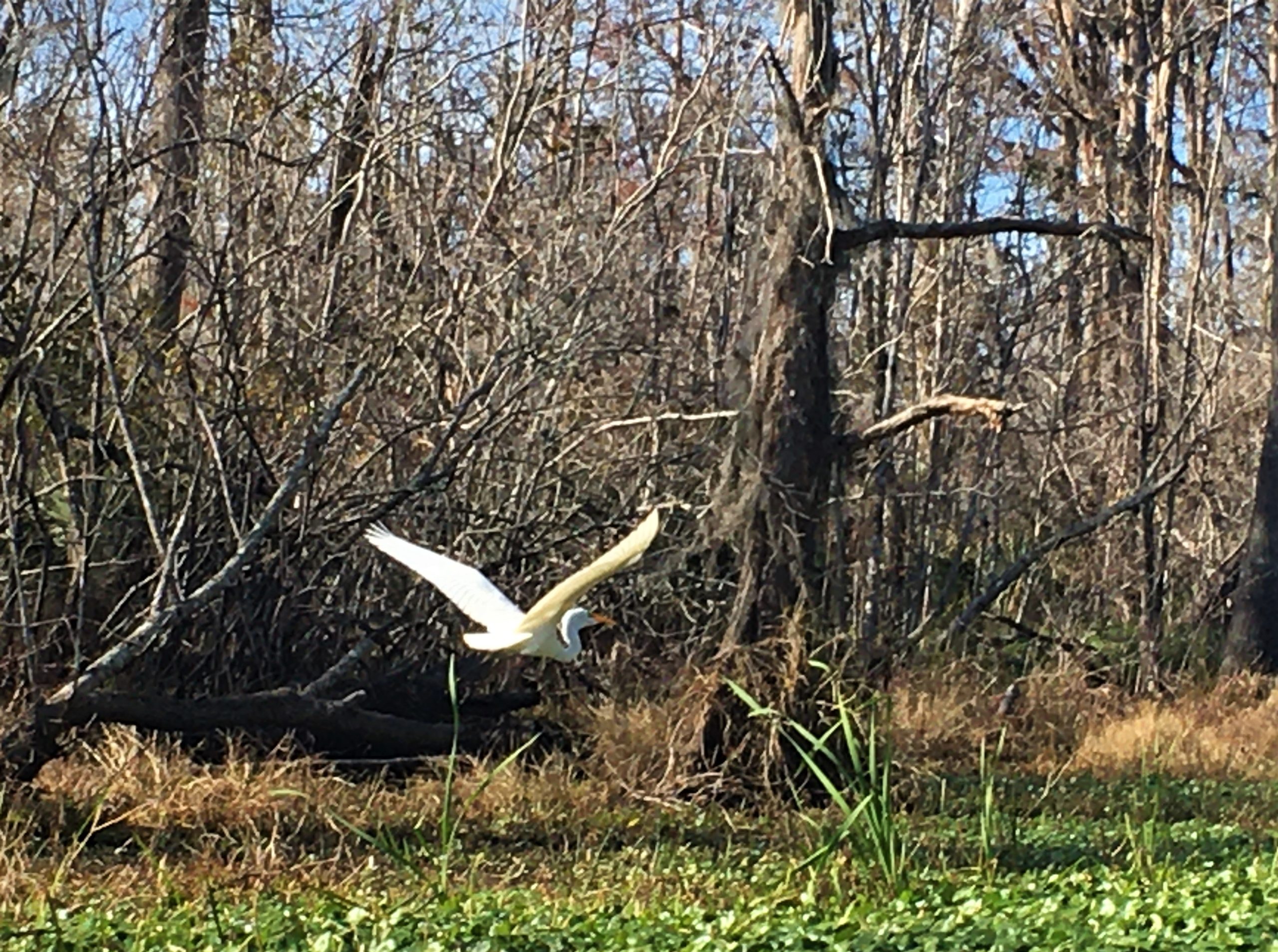

We saw one Giant Egret.

I saw a bald eagle. We saw more deer. Blaine saw a nutria. Yes, I’ll tell you what that is. 😊

The people of the bayou used to make money catching them and selling the pelts, and eating the meat. Maybe they still do. Nutria are kinda sorta similar to beavers – at least in size. In truth, they’re more like giant rats, with beaver-like front teeth an webbed feet.

They’re semi-aquatic and are indigenous to South America. They ended up in Louisiana in the 1930’s when someone decided to import them for the fur farming industry. They were released into the wild (no one knows if it was intentional or accidently). They quickly became a huge problem, and still are, causing extensive damage to Louisiana’s wetlands, rice, and sugarcane fields. Today, there’s a bounty to be collected – the State will pay you $6/tail during Nutria season. (I don’t know why they need a season) To give you an idea of the numbers, in the mid-1950s, they calculated a population of 20 million! They’ve been on the protection list, taken off, and put back on several times. From 1962-1982, 1.2 million were ‘harvested’ annually for the fur industry. And then most people stopped buying fur and in 1991, only 134,000 were harvested, so the nutria were back at it; eating all the hurricane protection foliage in the bayous. In 2002, the state started the bounty program. During the 2021 trapping season, 312,118 nutria tails worth $1,872,708 in incentive payments were collected from 284 active participants. If each person caught the same amount, that’s 1,100 each and an income of $6,594. That’s a lot of tail-chopping!

Supposedly it’s good for you – high in protein, low in fat . . . .

I’ll try it if you do. 😊

We discovered this wonderful place for a nice leisurely lunch! It was warm, quiet and beautiful!

When we were ready to move on, we took our stuff – all our stuff – back to the Jeep but walked back to the water again where we considered whether or not we could paddle here, and as we were discussing if/how we could get the boat in the water (and even more importantly – – back out!), Blaine started testing the ground to see if we could walk on it. He was okay on a root, but when he stepped to the ground, he sunk in up to his knees!! And of course his other foot followed. It was scary! But he got out. Whew!! And me without a camera! He was a royal mess!!

Sure can’t tell much now, and it looks like solid ground, doesn’t it?

Unfortunately, we think something bit him while he was in there. When we returned home, we discovered why his foot had been itching – getting gradually worse and worse as the day wore on. He now has a place on the top of his foot and on his Achilles tendon, each with two “fang” marks! His foot is swollen and itches like crazy.

We decided on trying to paddle one of the canals off the Intercoastal Waterway in the area where Blaine had found a boat launch online.

Unfortunately, the canal was very short! It was gated off by a “Private Property” sign! To save face from the guys fishing off the boat launch (because we spent all that time setting up and such a short time paddling, which we were sure they were aware of), we turned right and paddled up the intercoastal for a few minutes before returning.

We weren’t satisfied. So we went back to our lunch spot, dropped the boat in, and off we went. It wasn’t a long paddle (stopped by a wide swath of that green stuff that’s hard to paddle through), but it was longer than the canal. And it was beautiful!

That’s the stuff thats vine-y and difficult to get through, even though it only grows on the surface of the water.

It closed up almost as soon as we passed through it!

And when we returned, Blaine hoisted that boat right up onto the platform all by himself! What a man! He did it so quick, I didn’t get a picture. ☹