As you’ve seen, I’ve spent an enormous amount of time listening, learning and researching things revolving around Gettysburg, but from almost the beginning of the very first talk that Jarrad gave us, I still kept coming around to the same question. . . .

What happened to the people of the town of Gettysburg? What was this battle like for them?

After what little I was able to uncover (it would seem, not many want to discuss that part of the Civil War for some reason), I believe it’s something we can’t even begin to imagine, but I’m going to try to at least get you thinking, because for me, those left in the wake of this horrific war fought in our very own country between our very own people – often between brothers and fathers and sons, family against family – these people who were left to wallow in the Aftermath – are every bit as much heroes as those who picked up a gun.

Many Americans today are familiar with the battle of Gettysburg. Most read about it in history books growing up. But it is very difficult to appreciate the savagery, the barbarity of the fight, or the sheer volume of carnage that afflicted both sides. While the battle itself is known by most Americans, few are aware of the aftermath of the fight. A description of what happened on the field of battle after the two armies moved on to continue the fight elsewhere, deserves our attempt at understanding.

As mentioned previously, there were approximately 2,400 residents of this busy little town of approximately 25 square miles. In today’s society, in a city with several-story apartment buildings, there’d be approximately 5,000 residents per square mile, which comes out to about 125,000 in 25 square miles.

And then, at the end of June, 1863, troops began arriving around town. By June 30th, 170,000 soldiers appeared in and around the town, swelling the population overnight like a swarm of locusts.

We’ve already covered the three-day battle; as much as I’m willing to spend on it anyway. On July 4th, in the pouring rain, the Confederate troops began leaving Gettysburg and the Union troops followed close behind them on July 5th. They were a far cry from today’s “No man left behind.”

In this post, I want to share what the 2,400 residents who were left to clean up, had to face. And only a portion of those people were able to help out, because some were children and others had fled when the troops began arriving – especially the freed and independent black population. Some of the pictures you’ll see were taken inside the Gettysburg Visitor Center Museum, but many I found on-line.

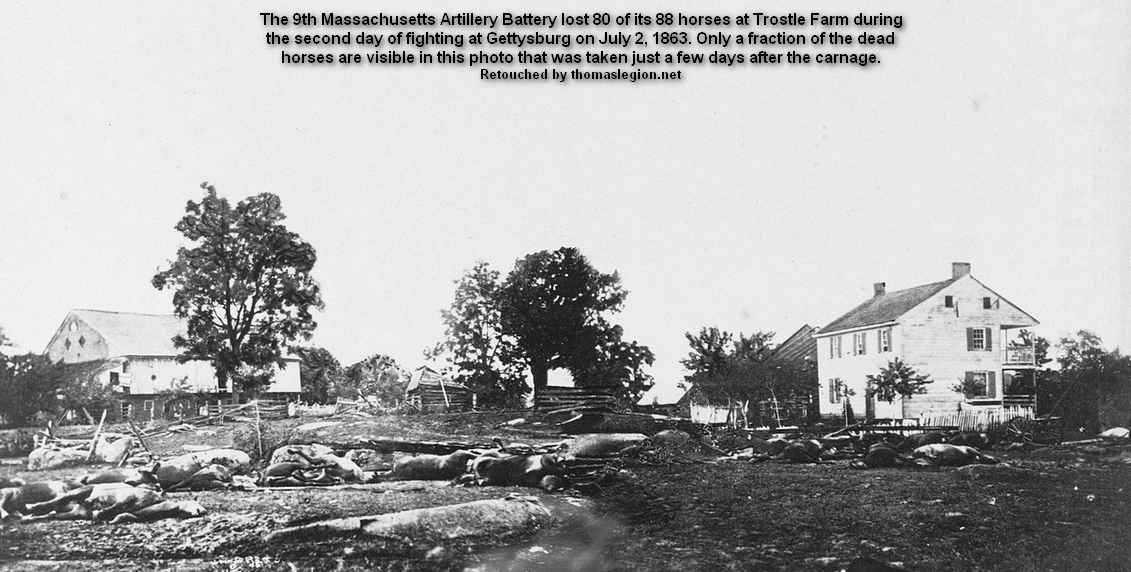

Left behind were at least 7,000 dead scattered everywhere, 21,000 wounded (this total is roughly the number of people in Progressive Field in Cleveland on an average night.), and roughly 5,000 dead horses and mules – some from each side. And a handful of Army surgeons and attendants. Before we get into what this means, let’s look at basic survival.

There was a severe shortage of food and drinkable water caused by 170,000 men and thousands of equines (tons and tons of hay were consumed) needing to eat and trampling all the crops in their battle or even just walking around, and also relieving themselves pretty much everywhere.

On June 26, the Confederates had destroyed the bridge what would allow a supply train to come to town. Fortunately, it was repaired by July 7th. Telegraph wires were down as well, cutting off all communication.

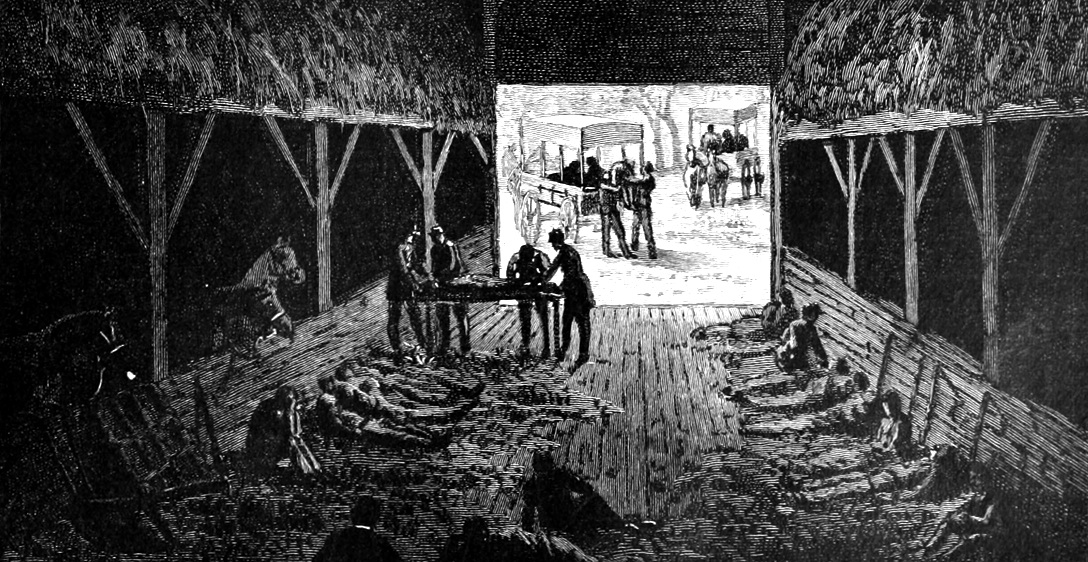

By the end of the first day of battle, Gettysburg was overrun by the wounded. All public buildings – including churches and the Adams County Court House – were converted into hospitals, as well as at least 45 of the town’s 300 private residences. To the south and west of downtown, the armies also created field hospitals – as many as 160 of them – in barns or other out buildings. Even then, many wounded were left out exposed to the elements because there simply was no more room for them. As if these things weren’t bad enough, the surgeons were practicing in an era before the germ theory of disease was established. Before sterile techniques and antiseptics were known, and very few effective medications were available. They also worked, operating non-stop for 48-72 hours with no sleep. No one knows for sure how many physicians were there to treat the 33,000 battle-wounded soldiers starting on July 1st.

One witness’ account said that one of the barns was so full, they couldn’t step between the men.

And at some point, they all would’ve had to go to the bathroom . . .

At one church, they laid boards across the pews to use as beds, and surgeons set up an operating table in the vestibule so the open doors could provide light. One soldier, Henry Huidekoper, a lieutenant colonel of the 150th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, tells of having to climb up onto that table to have his right arm amputated on July 1st. He took some chloroform, but apparently not enough because during the operation, he told the surgeon, “Oh, don’t saw the bone until I have had more.” Once he came to, he had to find a place to lie down on his own. After stepping over the hundreds of soldiers that were lying in the aisles, he worked his way back to the operating table and then climbed the stairs to the gallery (balcony) with no assistance. There were so many amputations that the surgeons tossed the limbs outside into great piles – arms, legs, hands and feet – a veritable feast for flies and carrion birds, and dogs. Keep in mind, it’s July and temperatures were approaching 100 degrees.

Church services were suspended for at least four weeks.

Even with all the field hospitals and buildings being utilized, thousands of wounded were still lying about naked and starving. One woman, Liberty Hollinger, took it upon herself to collect the army coats and place them over the bones. On one farm, a man went into the barn and discovered it crowded with wounded from both armies. Some of them having fallen four days before and had had no food or any attention to their wounds. In another barn, two wounded Confederate soldiers were discovered lying in the barn filth.

Many of the women of Gettysburg assisted in helping the wounded however they could – rolling bandages from their own clothes and bedding, making biscuits, or talking to the men. But first, they had to overcome their aversion to the immense amount of blood everywhere. They worked tirelessly until reinforcements from the United States Sanitary Commission and the Christian Commission, began arriving on July 7th. But then, all those people needed cared for too. And approximately 10-12,000 outsiders also began arriving – those hunting for loved ones and also those just there out of curiosity. People milling about and collecting souvenirs and hindering the work being done; so much so that the militia had to impose a 4pm curfew. One report said that by July 8th, the Globe Hotel had no space left because all the rooms were occupied by women, and the men were sleeping on the carpets and floors of the parlor and even in the loft of the stable. The town continued to open their homes to these strangers – for weeks afterwards.

Amidst all this, the United States Army was in the process of building a large hospital that would permanently take over the care and feeding of the wounded who were too seriously injured to be sent to other military hospitals. It opened on July 23rd and by mid-August, had over 1,600 Federal and Confederate patients.

Not only was the town dealing with human and animal carnage (which we’ll get into soon), but many also had their homes destroyed, either by musket or cannon fire, or ransacking by the soldiers. And then there was the stuff left behind – broken wagons, bits of clothing, weapons, ammunition of every kind and many, many undelivered letters strewn about the fields – just to name a few.

Widow Leister did not fare well. Not only was her tiny frame house appropriated to serve as General Meade’s headquarters, but the Confederate shot and shell which on the third day had rained down around it had created havoc. She recounted her woes to a visitor: Coverlids and sheets and some of our clo’es were all carried away. They got two ton of hay from me…. I’d put in two lots of wheat that year and it was all trampled down and I didn’t get nothing for it. I had seven pieces of meat, and them was all took. All I had when I got back was jest a little bit of flour. The fences was all tore down…. and the rails was burnt up. One shell came in under the roof and knocked a bedstead all to pieces for us. There was seventeen dead horses on my land. They burnt five of ’em around my best peach tree and killed it…. The dead horses spoiled my spring, so I had to have my well dug. Among the widow’s catalog of injuries was that at the time (August 1865) she had received no compensation other than from the sale of the horse bones and even then she had to wait ” ’till this year for the meat hadn’t rotted off yet.’

So now we’ve talked about those who survived. Let’s talk about another real issue. The dead.

I’ve smelled this kind of death before. When I worked at an animal hospital, we had a freezer in the back where we kept deceased animals until the burial service could pick them up. One Monday, I arrived first at work to discover an awful, indescribable, gut-wretching stench. The freezer had stopped working over the weekend. Not only were the couple of bodies closed up inside a sealed freezer, they were also encased in heavy plastic bags, and yet, the smell still permeated the entire office. We ordered an emergency pick-up and once they were removed, it fell to me to clean up the mess – including trying to deorderize the office.

A 23-year-old woman who came from New Jersey to volunteer named Cornelia Hancock wrote home and talked about the stench:

A sickening, overpowering, awful stench announced the presence of the unburied dead upon which the July sun was mercilessly shining and at every step the air grew heavier and fouler until it seemed to possess a palpable horrible density that could be seen and felt and cut with a knife …

She was so overcome by the smell that she viewed it as an oppressive, malignant force, capable of killing the wounded men who were forced to lie amid the corpses until the medical corps could reach them. Her account, vivid in its horror, proves the limitations of the visual record of war. No photograph of the aftermath of the battle, could capture the sounds, the groans or the rustle of twitching bodies and no image could ever capture that smell.

I’ve also seen death. I’m not talking about prepared bodies in a funeral home, I’m talking about a real, honest-to-goodness dead body. Blaine and I were driving on a near empty expressway very early in the morning in Arizona and a man had hurled himself off an overpass. The police had arrived, but we still were able to see the man. Let me tell you. No amount of death on TV or in the movies or in funeral homes can come even close to seeing a person actually lying dead on the road. It was heart-wrending and beyond description.

Imagine if you can. At the end of the battle, there are over 7,000 dead men lying about exposed to the elements (that’s about the same number of people who can fill Canal Park Statium in Akron, Ohio), as well as approximately 5,000 horses and mules. And there are roughly 33,000 wounded and many limbs in great heaps. Historians have recorded that the smell of the battlefield could be detected from far away. Residents carried around bottles of peppermint oil and pennyroyal to try to mask the stench.

were quickly consumed by insects, decay and sometimes hogs and other animals.

One man eventually gave his home away “to an old Dutchman” because the smell had permeated the very walls of the house and his family could no longer tolerate it.

In addition to the smell, they had to deal with decomposition. (which of course is the reason for the smell) When we die, if left undisturbed by embalming, our bodies go through five stages, and this is if the conditions are good – like inside a house furnished with air conditioning.

1. 24-72 hours after death, the internal organs are decomposed.

2. 3-5 days after death, the body begins to bloat and blood-containing foam leaks from the mouth and nose.

3. 8-10 days after death, the body turns from green to red as the blood decomposes and the organs in the abdomen accumulate gas.

4. Several weeks after death, nails and teeth fall out.

5. One month after death, the body begins to liquify.

Laying about in the rain and sun and summer’s heat would’ve greatly sped up the process. In addition, many of those who were interred were only in shallow graves to start; many graves with numerous bodies in the trench that often was only 4″ deep. Many Confederates weren’t buried at all. Both Union and Confederate were soon exposed by rain run-off, and animals (like dogs and wild hogs) tore them asunder.

And of course, there are the flies and maggots.

And the carrion birds who ate until they had their fill.

A Union surgeon at one battle site recorded that “stretched along, in one straight line, ready for interment, at least a thousand blackened bloated corpses with blood and gas protruding from every orifice, and maggots holding high carnival over their heads.”

And most were re-buried at least three times, meaning that they had to be dug up and moved. Can you imagine?!?

The horses, their bodies sometimes torn to pieces from cannon fire, were burned and that smell also cast a pall over the town for weeks.

A call for help in cleaning up was issued in the local newspaper, The Compiler:

To all Citizens

Men, Horses and Wagons wanted immediately, to bury the dead and cleanse our streets in such a thorough way as to guard against pestilence. Every good citizen can be of use.

And still the perils continued. There were an estimated 24,000 unexploded shells, bullets and loaded guns left on the battlefield. People were killed, and also farmers and their teams when their plows came into contact with them.

Today, it is practically impossible to even imagine this scene from just visiting a few days in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. I found this excerpt by Brian Mockenhaupt, a former Army infantryman:

“Carrying long-dead bodies is fairly far along the spectrum of citizen involvement in war. Today we live at the other extreme, in which nothing is asked of us. For the most part, lives here have gone on just the same over these many years of war. Our homes are not destroyed or filled with wounded. Our streets and parks and fields are not strewn with dead.

The people of Gettysburg were forced into involvement; we have the luxury of ignoring war. But while distance may insulate us from war’s effects, it does not lessen our moral obligation as citizens to be aware of what is done abroad on our behalf.”

If the newest estimates are correct, 850,000 men died in the Civil War (out of 31 ½ million total). That’s roughly the population of Columbus, Ohio or four times the population of Akron today. Their entire populations. Now add to that wives, mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, children . . . . Well, you can see, millions and millions were greatly affected in some way. And that’s just the deaths. How many more suffered life-altering wounds? Or lost everything they owned?

Two of several ‘Then and Now’ photos the National Park Service has on their website.

Have you ever considered what may have happened to our country if the South had won? Most likely there would no longer be a United States. Would we belong to some other nation?

United we stand. Divided we fall.

We owe a great debt to these brave men and women – both those who were actively involved in fighting, and those who had to face the Aftermath all over our country. Below are but a few of the civilians who stepped up in Gettysburg.

Civilians at Gettysburg