Catalina State Park, Tucson, Arizona

A wicked man puts up a bold front, but an upright man gives thought to his ways. ~ Proverbs 21:29

Before we moved, we returned to the laundromat. Today, they had pages laid out about COVID-19 and laundry. Thought you might find it interesting, so . . . .

Time to pack it up and head out to the next wonderful place God has in store for us!

That’s the barbed wire on the right.

It’s an RV Resort. : )

See all the little hills in it?

Unfortunately, in these times, it seemed like it was closed. : (

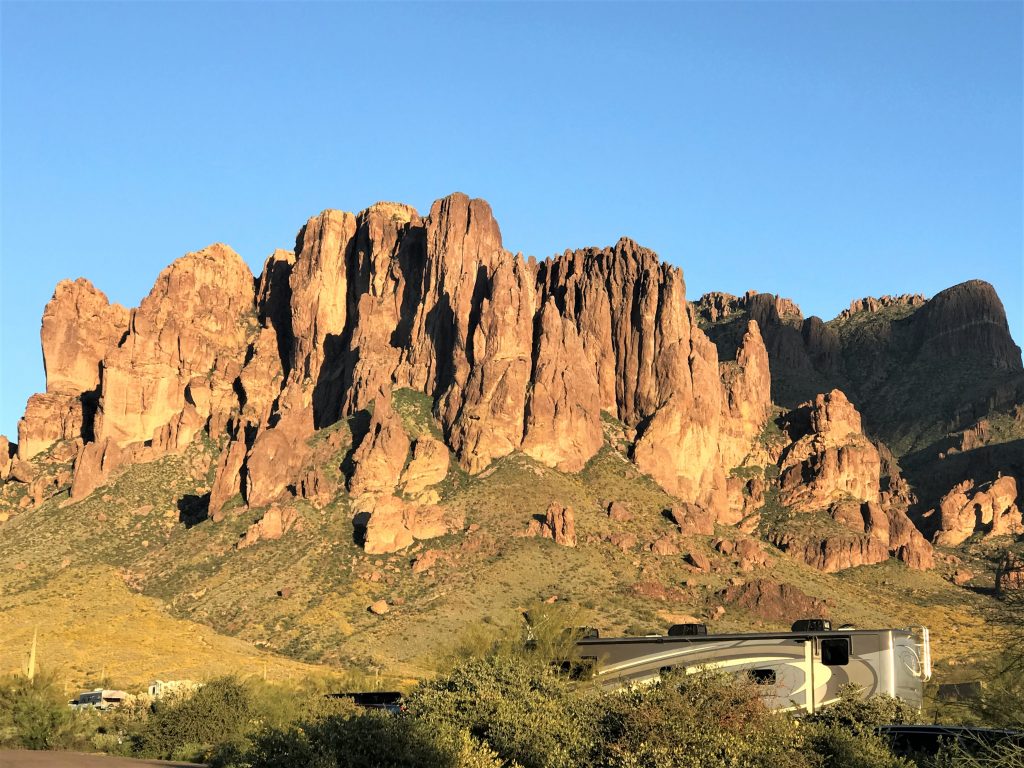

Lost Dutchman State Park, Apache Junction, Arizona

Can you believe it?!?!

Did Blaine do great on this reservation, or what?!?!?

We get to look at this every day for the next nine days!!

Once we arrived, we didn’t do much except gawk at the mountain in our yard. It’s part of the Superstition Mountains.

And we also researched why this place is called ‘Lost Dutchman’. Here’s part of what I found:

BY DAN GLEASON/CowboysandIndians.com JANUARY 1, 2018

There’s gold in them there hills — or is there? In the Superstition Mountains outside of Phoenix, people have died trying to find out.

In 2009, Denver bellhop Jesse Capen, obsessed with finding the Lost Dutchman gold mine, took a month’s vacation into the Superstition Mountains outside Phoenix to search for that legendary treasure. It was three years before a search-and-rescue team located Capen’s skeletal remains at the bottom of a 180-foot cliff.

His fatal mistake was likely going up there alone.

No matter the risks, this alleged mother lode lures hundreds of prospectors every year into this wilderness near Apache Junction, Arizona — occasionally at the expense of their lives. German immigrant Jacob Waltz, nicknamed “the Dutchman,” took his secret to the grave in 1891, at around the age of 83. Lending credibility to the lore, Waltz had remarkably high-grade gold ore in a candle box under his deathbed. It was rumored he had dictated to some neighbors a complicated map, but neither they nor anybody else ever found his mine.

A few reasons why the Dutchman’s gold hasn’t been found and some treasure-seekers didn’t come out alive: Magnetic rock fouls up compasses, summers in the Superstitions can be fatally hot and winters deadly cold, cell phones won’t work up into the higher reaches, and the cliffs are treacherously steep.

George Johnston, who first tried to find the treasure in the 1950s, was still working for the Superstition Mountain — Lost Dutchman Museum up until his August 30, 2017, death at age 97.

“Most people don’t take enough water and they often wear slacks or shorts and flat shoes,” Johnston said in a 2016 interview. “If they sprain an ankle and are alone, they can kiss their lives goodbye.”

Johnston, who grew up in New York, first heard about the Lost Dutchman from a cover story in Life in 1937, when he was 16. He first visited Phoenix in the 1950s. “I took my two boys on a hike into the Superstitions, hoping we could find the treasure,” Johnston recalled. “After a while, my son spotted somebody watching us. I kept seeing a reflection behind us from something metallic, like a rifle or pistol. I am sure somebody was stalking us. Folks had claims all over those mountains and would commonly fire warning shots to scare trespassers — or even now and then murder those they thought were seeking the Dutchman’s gold. Nobody went in unarmed.”

Though Johnston lived to tell his tales, some haven’t: In the last 125 years, more than a few “Dutch Hunters” have lost their lives looking for that fabled gold mine. “This is a rugged wilderness area in terrain and temperature changes,” Johnston declared. “Go up there in late fall wearing shorts and a storm can plunge temperatures so fast you can die of hypothermia. A few years ago, three guys from [Utah], who had trekked up there before, went looking for the Dutchman’s mine in June. A storm came through one night and they all died of hypothermia.” The mountains are also full of box canyons, where it’s easy to become disoriented — and you must walk out the same way you walk in, which is easier said than done.

One theory why nobody has found the mine is that Waltz might have even been a claim jumper who hid stolen loot up there in a dugout and made trips whenever he needed money.

But his gold was genuine: Three neighbors took the gold ore from under Waltz’s bed when he died, claiming he told them they could have it. Some was sold to a San Francisco mint; some was made into a necklace and matching bracelet; some was shipped to a jeweler and fashioned into a matchbox case that measures 4.5 inches long by 1.5 inches wide.

The matchbook case was lent by its current owner to the Superstition Mountain — Lost Dutchman Museum to be showcased for one day in November 2015, and a photograph of the case is now a permanent display there. “To give you an idea of how rich that ore was,” Johnston explained, “if a mine produces two and a half ounces of gold per ton of rock, it is a bonanza. Well, the Dutchman’s gold ore that made that matchbook case assayed out to 50 ounces per ton.”

The Lost Dutchman legend also has a link to wealthy Mexican cattle ranchers of the 1800s, the Peralta family from Sonora, who supposedly dug many gold treasures out of the Superstitions. Their plundering ended in 1848, or so the tale is told, when on a gold run back to Mexico all but a few got massacred by Apaches. Some say the Apaches went back to the mine and hid the gold, and the Dutchman either stumbled across it or did a favor for a surviving Peralta, who directed him to the stash.

Both allegations and actual incidents have fueled the legend over the years, none more than the “Peralta Stones,” found in 1949 in the Superstition foothills. A hiker literally tripped over a sharp piece of rock and dug up four flat stones on which were carved instructions and a crude map. The carvings included a priest holding a cross; the words Sonora, Mexico; a horse; and words that translate to “I pasture north of the river” (where the trail starts into the Superstitions near the Salt River). Other carved messages mention “dangerous canyon walls” and “18 marked places” to get to “el corazón” (the heart). Two stones are rough maps leading to a carved heart, the supposed treasure location; centered in the heart is the date 1847, one year before all but a few Peraltas met their doom.

Dutch Hunters are convinced those stones refer to the Dutchman’s mine and that the Peraltas carved them to find their way back. An expert who once examined the stones believed the carvings were made with modern tools and are a hoax — but there’s no way to prove that. Replicas and pictures of the stones remain on display at the Superstition Mountain — Lost Dutchman Museum in Apache Junction. The actual stones are in the care of Greg Davis, director of research, acquisitions, libraries, and archives for the Superstition Mountain Historical Society. Viewable by appointment, the stones are kept in a large room built onto Davis’ Tempe, Arizona, home.

Along with an assortment of rumors and yarns, those stones keep the legend alive and the hopeful hoping.

Wonder if we’ll be the ones to finally find it??? 😊