Highlands Hammock State Park, Sebring, Florida

Hammock. Not the kind you laze around in between two trees. This is “hammock: area that is often higher than the surrounding land with humus rich soil and hardwood trees including oaks, sweetgums, hickories, and palms.”

FYI – you won’t find this definition in the dictionary. They only mention the ‘rope bed’.

It was only a 45 mile move today, so this morning before we left, we took the bikes back out for a short hunting trip. We were hunting for scenery, birds, reptiles, anything exciting. Our Excitement Gage was on low and it barely crept up above its resting position (with the exception of the alligator!).

These turkeys were running alongside the road in the campground.

They didn’t much care for us trying to take their picture. : )

But that was this morning. . .

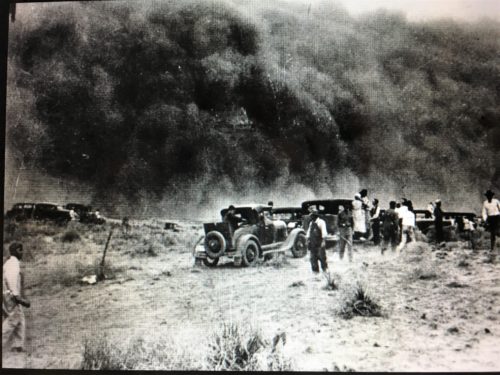

This afternoon, we encountered a dust bowl that invaded our home.

Initially, we were very pleased (especially Blaine) that they had graded the road that leads from the campground to the exit. Until we got to our next site. And I discovered that yellow dust was covering every single surface in this place! And looking at it, brought to mind the Dust Bowl of the 1930’s prairies out West.

When we first left, we smelled dust, but Blaine made some vent adjustments and the smell went away.

Only the dust didn’t.

So at 2:30pm, I started cleaning. Working as fast as I’m capable of, I wiped/washed every surface from back to front. I was finally finished about 5:30pm. Blaine stayed outside and did a few things, plus the laundry, staying out of my way. Much like I did for him during the power outage fiasco. 😊

I think God planned this.

I was tremendously irritated when we left Kissimmee over something in Ohio, so having to clean and Blaine staying outside, provided the perfect opportunity for me to voice my opinions loud and clear. Not that He particularly cares about what my opinions. But it’s good to talk them over with Him. He reminded me that He’s still on the throne and He knows exactly what’s going on and knows exactly what He plans on doing about it. “My ways are higher than your ways, and My thoughts than your thoughts.” Isaiah 55:9

By the way, we’re in site #130 today. It’s a handicapped site. For some reason, that’s not an issue. Remember this site number. You’ll learn why later.

I’m not slouching. This is how high the table is!

Stuffed peppers for dinner. I don’t stuff, I just cut up and mix like a casserole. Much easier! : )

I don’t look too bad, considering I just finished battling our own Dust Bowl!

Needless to say, we didn’t do much else today.

I did however, research the Dust Bowl. Here’s what I found on history.com:

The Dust Bowl was caused by several economic and agricultural factors, including federal land policies, changes in regional weather, farm economics and other cultural factors. After the Civil War, a series of federal land acts coaxed pioneers westward by incentivizing farming in the Great Plains.

The Homestead Act of 1862, which provided settlers with 160 acres of public land, was followed by the Kinkaid Act of 1904 and the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909. These acts led to a massive influx of new and inexperienced farmers across the Great Plains.

Many of these late nineteenth and early twentieth century settlers lived by the superstition “rain follows the plow.” Emigrants, land speculators, politicians and even some scientists believed that homesteading and agriculture would permanently affect the climate of the semi-arid Great Plains region, making it more conducive to farming.

This false belief was linked to manifest destiny—an attitude that Americans had a sacred duty to expand west. A series of wet years during the period created further misunderstanding of the region’s ecology and led to the intensive cultivation of increasingly marginal lands that couldn’t be reached by irrigation.

Rising wheat prices in the 1910s and 1920s and increased demand for wheat from Europe during World War I encouraged farmers to plow up millions of acres of native grassland to plant wheat, corn and other row crops. But as the United States entered the Great Depression, wheat prices plummeted. Farmers tore up even more grassland in an attempt to harvest a bumper crop and break even.

Crops began to fail with the onset of drought in 1931, exposing the bare, over-plowed farmland. Without deep-rooted prairie grasses to hold the soil in place, it began to blow away. Eroding soil led to massive dust storms and economic devastation—especially in the Southern Plains.

The Dust Bowl, also known as “the Dirty Thirties,” lasted for about a decade, but its long-term economic impacts on the region lasted much longer.

Severe drought hit the Midwest and Southern Great Plains in 1930. Massive dust storms began in 1931. A series of drought years followed, further exacerbating the environmental disaster.

By 1934, an estimated 35 million acres of formerly cultivated land had been rendered useless for farming, while another 125 million acres—an area roughly three-quarters the size of Texas—was rapidly losing its topsoil.

Regular rainfall returned to the region by the end of 1939, bringing the Dust Bowl years to a close. The economic effects, however, persisted. Population declines in the worst-hit counties—where the agricultural value of the land failed to recover—continued into the 1950s.

During the Dust Bowl period, severe dust storms, often called “black blizzards” swept the Great Plains. Some of these carried Great Plains topsoil as far east as Washington, D.C. and New York City, and coated ships in the Atlantic Ocean with dust.

Billowing clouds of dust would darken the sky, sometimes for days at a time. In many places, the dust drifted like snow and residents had to clear it with shovels. Dust worked its way through the cracks of even well-sealed homes, leaving a coating on food, skin and furniture.

Some people developed “dust pneumonia” and experienced chest pain and difficulty breathing. It’s unclear exactly how many people may have died from the condition. Estimates range from hundreds to several thousand.

On May 11, 1934, a massive dust storm two miles high traveled 2,000 miles to the East Coast, blotting out monuments such as the Statue of Liberty and the U.S. Capitol.

The worst dust storm occurred on April 14, 1935. News reports called the event Black Sunday. A wall of blowing sand and dust started in the Oklahoma Panhandle and spread east. As many as three million tons of topsoil are estimated to have blown off the Great Plains during Black Sunday.

An Associated Press news report coined the term “Dust Bowl” after the Black Sunday dust storm.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt established a number of measures to help alleviate the plight of poor and displaced farmers. He also addressed the environmental degradation that had led to the Dust Bowl in the first place.

Congress established the Soil Erosion Service and the Prairie States Forestry Project in 1935. These programs put local farmers to work planting trees as windbreaks on farms across the Great Plains. The Soil Erosion Service, now called the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) implemented new farming techniques to combat the problem of soil erosion.

More stuff I never knew!

TOTAL HIKING MILES: 0

Year To Date: 140

Daily Average: 3.04 (I think we better get off the bikes and walk more . . . soon!)