Cumberland Mountain State Park, Crossville, Tennessee

HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO OUR NEPHEW, LOGAN! He’s officially a teenager now!

The temperature dropped about 30 degrees from yesterday! But the sun’s shining brilliantly, so after waiting until after lunch, we headed out with the intent of strolling around the campground some and also acquiring some answers to questions we had.

Yes. We can put our kayak in the water anyplace we want.

Yes. They serve a bbq buffet in the restaurant on Saturday. They serve two different buffets nearly every day of the week – one for lunch, different one for dinner! We plan on trying it out. Hopefully it will be good – it’s only about $12-14 per person.

Once we we got all our answers, we started walking.

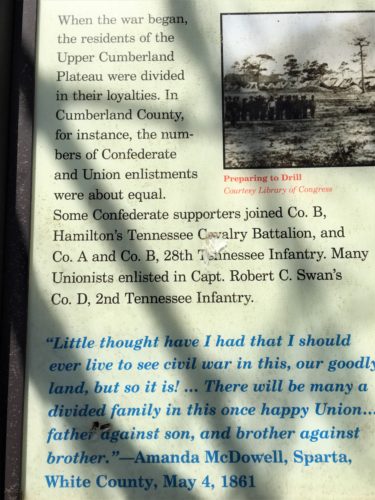

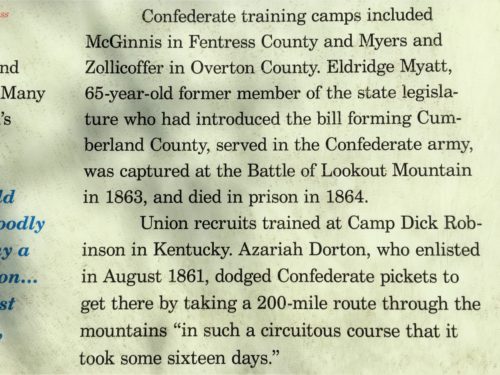

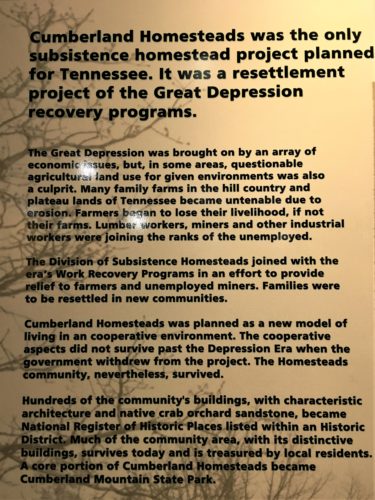

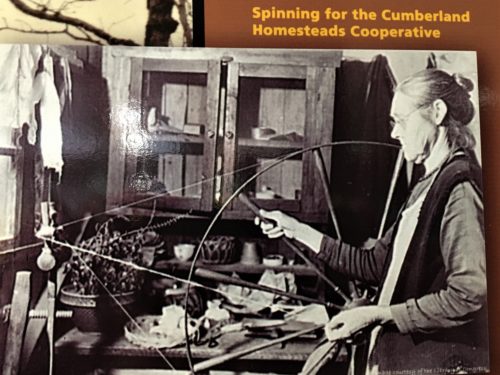

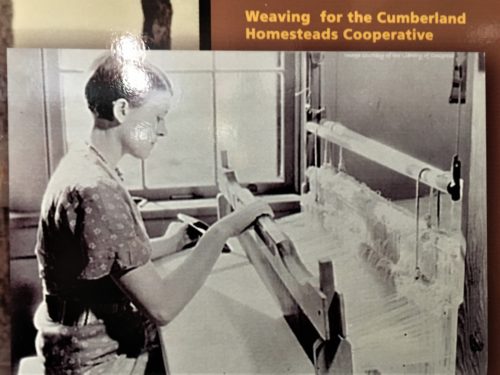

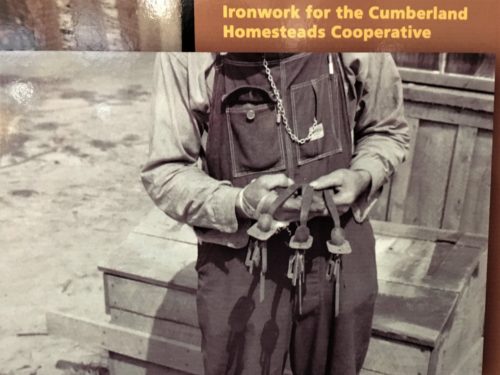

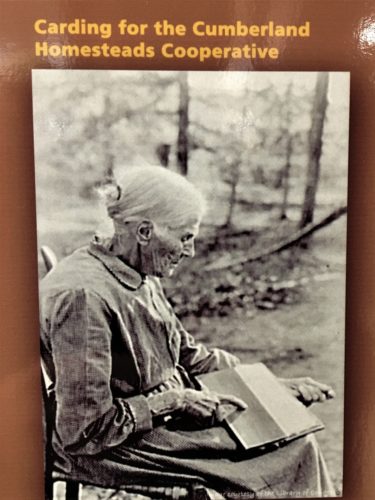

As we left the office, there was an information board. Interesting stuff – at least we thought so.

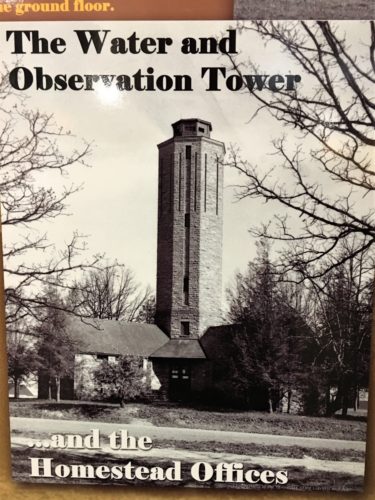

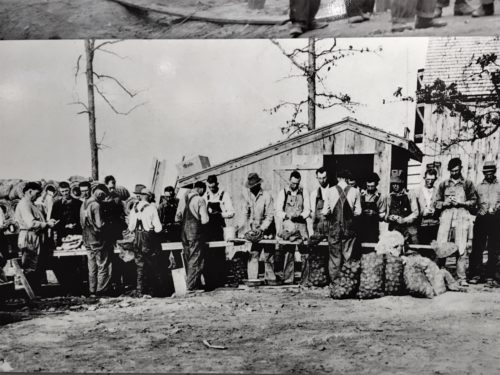

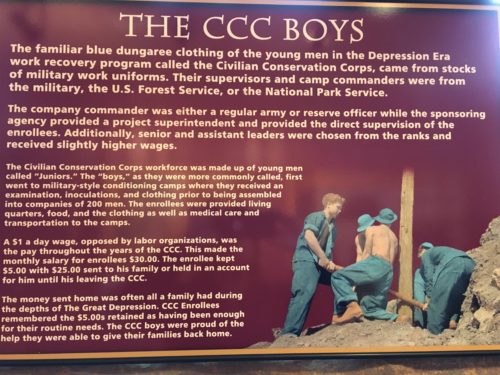

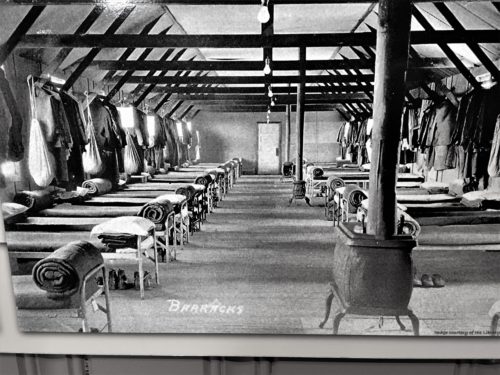

We didn’t get very far – just across the bridge – before we ran across their CCC Museum. Less information than the last one we were in (remember the prescribed burn right at the museum at Highlands Hammock in Florida?), but still some new and interesting blog material.

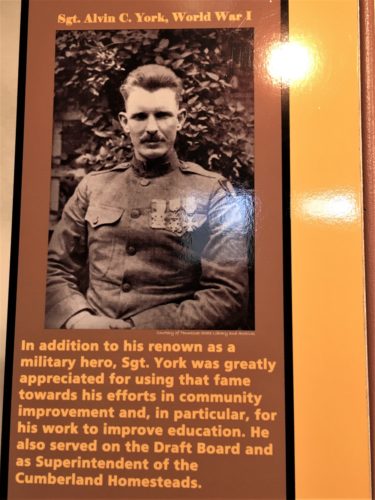

Do you know Sgt. York? We’d heard the name, but just thought it was an old movie or something. Turns out, he was a real person – and in 1941, they actually did make a movie about him.

Guess who you’re going to learn about today? 😊

Alvin York was one of the most decorated war heroes of WWI. Born December 13, 1887 in Pall Mall, Tennessee, about an hour north of where we are in Crossville, he grew up under-educated (only finishing third grade) before being drafted into the Army for WWI.

Unfortunately, the best information I could gather is from Wikipedia. I don’t like using them – or at least not solely them – because their information isn’t always accurate, but it seems to jive with some of the other things I read. I’ve interspersed their text with additional information I uncovered.

Alvin Cullum York (December 13, 1887 – September 2, 1964), also known as Sergeant York, was one of the most decorated United States Army soldiers of World War I. He received the Medal of Honor for leading an attack on a German machine gun nest, taking 35 machine guns, killing at least 25 enemy soldiers, and capturing 132. York’s Medal of Honor action occurred during the United States-led portion of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in France, which was intended to breach the Hindenburg line and force the Germans to surrender.

York was born in rural Tennessee. His parents farmed, and his father worked as a blacksmith. The eleven York children had minimal schooling because they helped provide for the family, which included hunting, fishing, and hiring out as laborers. After the death of York’s father, he assisted in caring for his younger siblings, and found work as a logger and on construction crews. Despite being a regular churchgoer, York also drank heavily, and was prone to fistfights. After a 1914 conversion experience, he vowed to improve, and became even more devoted to the Church of Christ in Christian Union.

York was drafted during World War I. He initially claimed conscientious objector status on the grounds that his denomination forbade violence. Persuaded that his religion was not incompatible with military service, York joined the 82nd Division as an infantry private, and went to France in 1918. In October 1918, as a newly promoted corporal, York was one of a group of 17 soldiers assigned to infiltrate German lines and silence a machine gun position. After the American patrol had captured a large group of enemy soldiers, German small arms fire killed six Americans and wounded three. York was the highest ranking of those still able to fight, so he took charge. While his men guarded the prisoners, York attacked the machine gun position, dispatching several German soldiers with his rifle. By the time six Germans charged him with bayonets he was out of rifle ammunition, so he drew his pistol and shot them all. The German officer responsible for the machine gun position had emptied his pistol while firing at York, but failed to hit him. This officer then offered to surrender, and York accepted. York and his men marched back to their unit’s command post with more than 130 prisoners. York was immediately promoted to sergeant, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross; a later investigation led to this award being upgraded to the Medal of Honor. York became a national hero and international celebrity; he went on to receive decorations from several foreign countries, including France, Italy, and Montenegro.

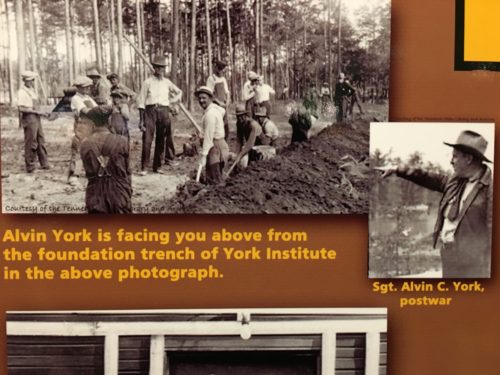

Businessmen in Tennessee organized the purchase of a farm for York, his new wife (and longtime love, Gracie Williams), and their growing family. And they began farming. He turned down all the celebrity deals, even vaudeville. There were no tours, no endorsements, no books. But he did start raising money to build a proper high school – which included mortgaging his home, twice. He later formed a charitable foundation to improve educational opportunities for children in rural Tennessee. The school was built and staffed in 1926. It’s still in use today as the York Institute in Jamestown, Tennessee and has bout 600 students.

This next section is the part where we were introduced to him. His work at the CCC.

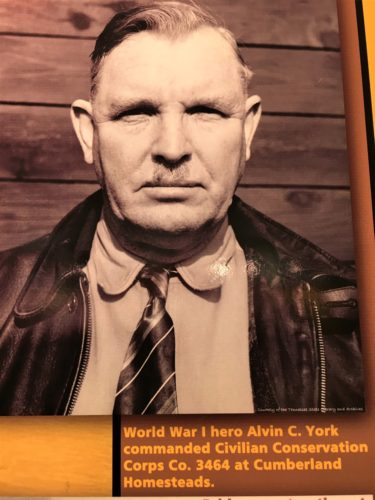

In the 1930s and 1940s, York worked as a project superintendent for the Civilian Conservation Corps and managed construction of the Byrd Lake reservoir at Cumberland Mountain State Park, after which he served for several years as park superintendent.

A 1941 film about his World War I exploits, Sergeant York, was that year’s highest-grossing film; Gary Cooper won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of York, and the film was credited with enhancing American morale as mobilization for World War II began in earnest. In his later years, York was confined to bed by health problems. He died in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1964 and was buried at Wolf River Cemetery in his hometown of Pall Mall.

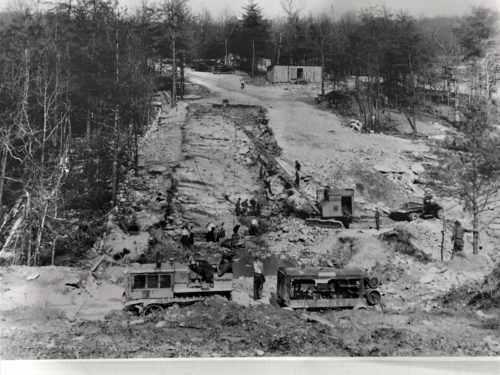

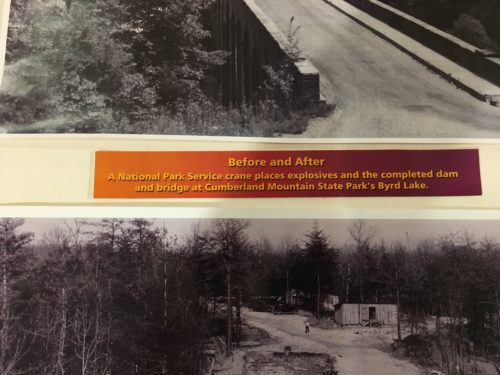

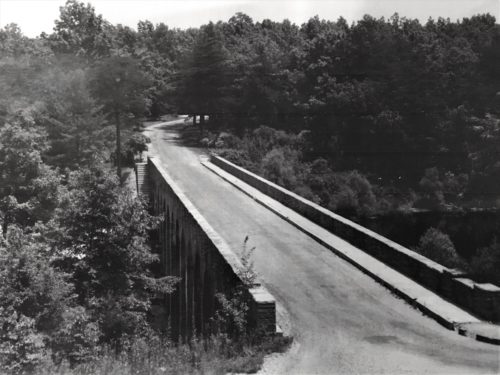

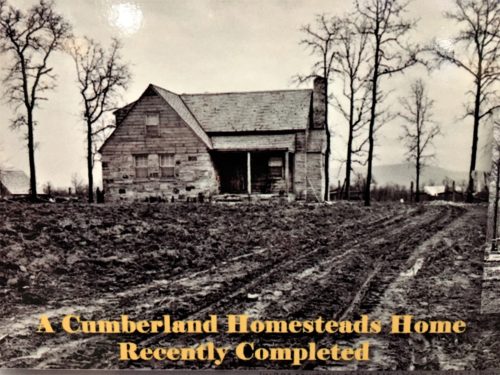

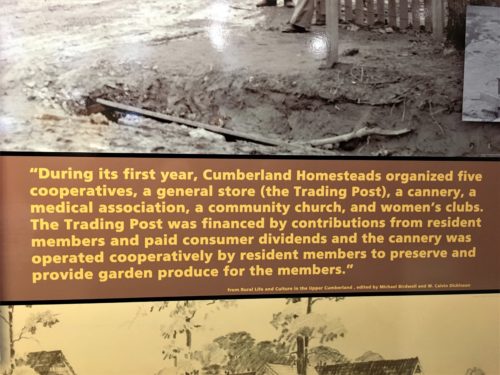

There was also information on building the bridge/dam and the “homesteads” the government built here. The dam is the largest masonry structure built by the CCC’s in the nation.

Before

After

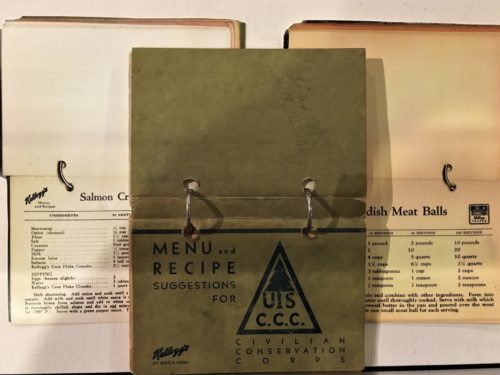

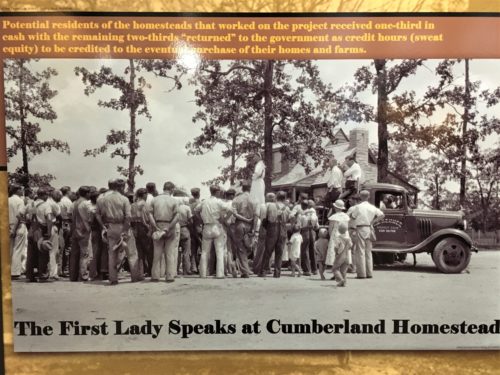

This was interesting . . .

Look who sponsored it. : )

After we finished there, we headed up an access road that said there were playgrounds and volleyball courts, etc. We were actually looking for the road to the cabins so we could check them out up close.

“Oh! Wonder where that goes?” There’s a trail off a parking lot, but there’s no marker of any kind. It’s not on the trail map either. I veered off course and Blaine followed.

Well, well, well. Seems they’re working on a mountain bike trail! No bikes today though. Just us and a guy training his German Shepherd puppy. So cute!! The puppy, not the guy!

Our little stroll around the campground, turned into a two mile hike. No water. Gasp. Throat clenching.

A pretty fall leaf!

Oh. Its silk.

Wonder where that came from?

These power lines were hanging really low!

That’s the same camper you saw in other pictures. We’re on the other side of it today.

There we are!

Water just a few steps away!!

That’s the extent of our adventure for today. And I haven’t forgotten about Marie Tussaud. I’m still working on her “biography” whenever I have a few minutes, so she’ll pop up eventually.