Edisto Beach State Park, Edisto Island, South Carolina

If someone says, “I love God,” but hates a Christian brother or sister, that person is a liar; for if we don’t love people we can see, how can we love God, whom we cannot see? I John 4:20

We learned a lot of stuff today. And then learned even more, once I set out to satisfy my curiosity.

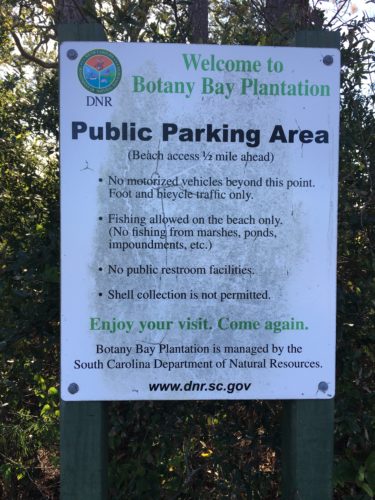

Following a lovely sunrise, and a hearty breakfast, Blaine took me to a nearby wildlife preserve called Botany Bay. He had read that it was a good place to visit – and free!, but we didn’t really know much about it.

Here’s what I found on their website:

Botany Bay is a 3,363-acre wildlife preserve located on Edisto Island. Its deed was transferred to the state after former owner John Meyer, who bought the property in 1968, illegally built a pond on the property. In order to avoid repercussions, he offered to give South Carolina the land upon his and his wife’s death. A deal was struck, and in 2008, the Botany Bay Plantation Wildlife Management Area was born.

A volunteer at the check-in point went over a few things, and gave us a few pointers and sent us on our way with a terrific (and quite large!) map and ‘post stops’ information, which I’ll use at times. Not everything was particularly interesting to us, so some were merely glanced at as we went on our way.

The first order of business was a drive to the beach. We were already two hours past high tide, and in a few more hours, the beach would be buried under water.

It’s a bit of a drive, and then a ½ mile walk to get to the beach here.

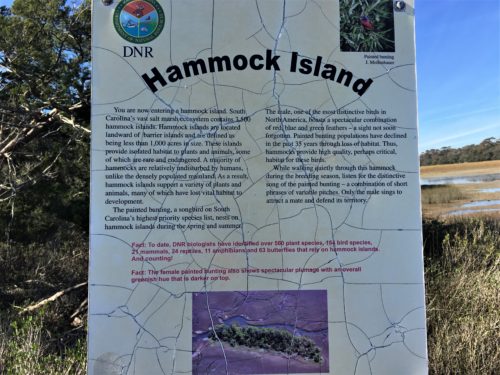

On the trail, we checked out a couple of interesting things.

Blaine’s panoramic view

K

K

One of them was this bush. There were quite a few of them. And they’re as soft as they look! Unbelievably soft!

After a bit of time searching the web, I was finally able to locate what it is. It’s actually considered a weed! A Groundsel Bush. It also can be invasive, but sometimes used in landscaping because it’s so pretty when it’s blooming (we can attest to that!). There are actually male and female plants (if you can believe it), and it’s the females that “take on a showy, cottony appearance due to masses of white bristles attached to the numerous tiny fruits, each containing a single seed. The bristles act like miniature parachutes, helping the seeds travel in the wind.” They also provide nectar for migrating Monarchs on their way south.

Do you remember last January, when we were on Jekyll Island and visited Driftwood Beach, and how disappointed we were that Hurricane Irma had washed all the trees out to sea?

Well, this beach is the way Driftwood used to be!

When you walk out, you are overwhelmed by it all! What a wonderful place!

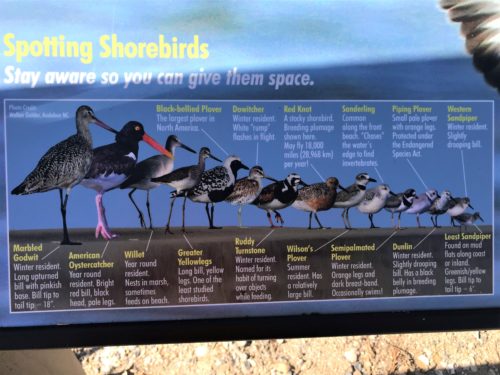

We didn’t see any of these . . .

It’ the same tree, I just swung around for better lighting. : )

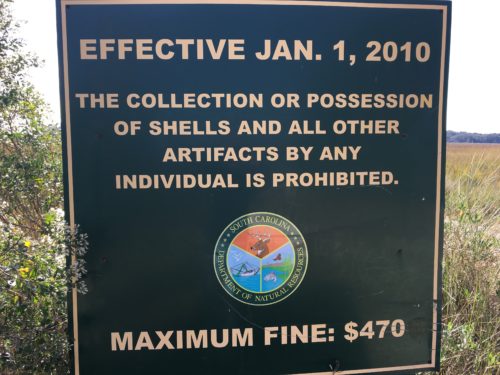

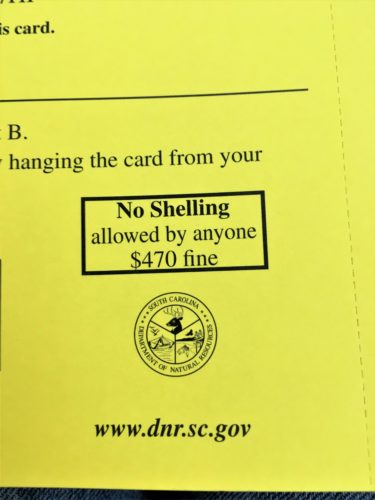

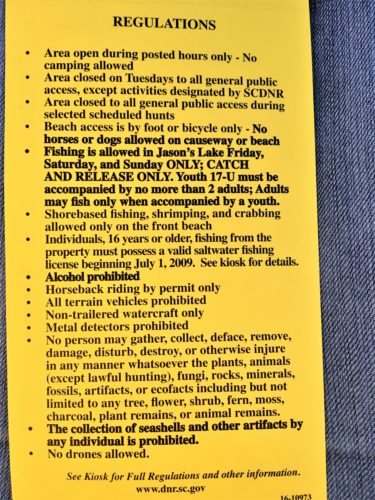

And it’s loaded with seashells as well! But be forewarned – there is absolutely, positively, unequivocally NO shelling allowed. The only thing you’re allowed to take from this beach – or even the entire Preserve – are pictures. The consequences of getting caught stealing shells from this beach? A hefty $470 fine!

In fact, there are a lot of rules here!

A dig – but for what?

Yep. I placed them.

There were a lot of conks here in various conditions!

We’re down at the end of the beach.

Very pretty here!

So, as we’re walking the beach and discovering all these really cool shells, we got to talking and wondering, “Just how are shells formed, anyway?”

You can just feel it, can’t you? More research and enlightenment on it’s way, straight to your screen! 😊

Shells are made by mollusks. Like me, you’ve probably heard the word, but don’t really know what it means, so let’s start with that. Mollusca is the second largest phylum of invertebrate animals. The members are known as molluscs or mollusks. Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is estimated between 60,000 and 100,000 additional species.

Clear as mud, right? This might help – snails, slugs, hermit crabs, clams, mussels, oysters, scallops, octopi, squid and cuttlefish, are just a few things in this category.

So now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s get on with it. . . .

Mollusks make only one shell. They use calcium carbonate and proteins, secreted from their mantles to build their shells. As a mollusk grows, so does its exoskeleton. “They are among the few animals on the planet that wander around carrying with them the same body armor they had as babies; the pointy tip or innermost whorl is the mollusk’s juvenile shell. Day by day, the mollusk shell slowly expands, making room for the soft animal growing inside.”

Most of the shells open on the right. If they’re unlucky enough to have a left-side one, they can’t reproduce.

Their shape is a product of their environment. Smooth shells, indicate few predators. Spiky elaborate shells indicate a need to ward off predators. Or so the scientists believe. They’re just speculating, but most likely don’t want to give credit to an amazingly creative Creator. 😊

Here’s a good one (more speculation). The elaborate colors and patterns on shells might be used to figure out where to put their mantles to continue making their shells.

Scientists have no idea what the mollusks use for pigment.

Hermit crabs use the shells of other dead mollusks. As they grow, they require larger shells. They don’t kill the owner of their chosen new home, they just hang around until it dies. (so does this mean they don’t make shells like the other mollusks???)

There are tons of shells that are left behind by mollusks that died from disease, predation, old age or some other fate, but those don’t remain in pristine condition for long. The ones you buy in souvenir shops, was most likely captured alive and killed.

The oldest shell collection? It was discovered preserved in the ash following the 79AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii.

We now return to our previously scheduled program . . . .

Heading back toward the entrance now.

Walking past the entrance and to the left of it.

This was washed up past the tide line.

We’ve gone about as far as we can go.

Time to head back.

This guy was hugging the coastline and really low!

I think we looked him in the eye as he came toward us!

This is the same tree Blaine was sitting on earlier.

Notice my feet are above the water. My left arm is really strong! : )

Back at the Jeep, we learned that we were sitting in the middle of nowhere.

And we learned a little bit about the Bleak Plantation. (Kind of a sad name, don’t you think? I would’ve changed it!)

This is the gardener’s shed

This is the back of the shed, but also shows the tabby wall.

This is the ice house, but it was also used as a carriage house, a place to air dry crops and general storage.

Here’s the inside.

The ice house was in under the floor.

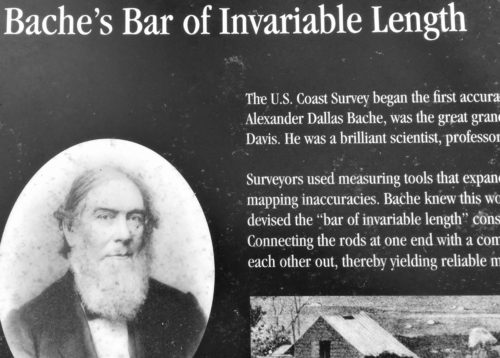

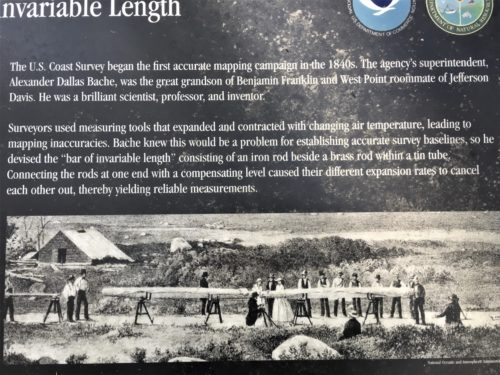

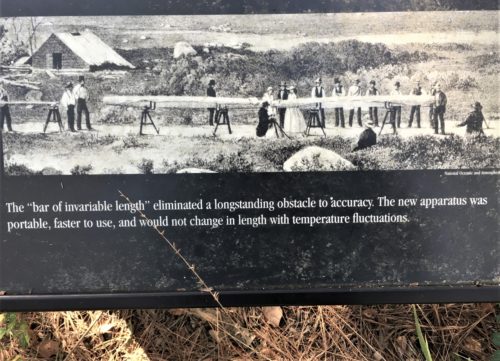

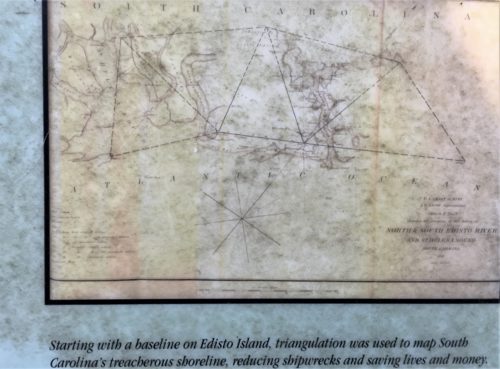

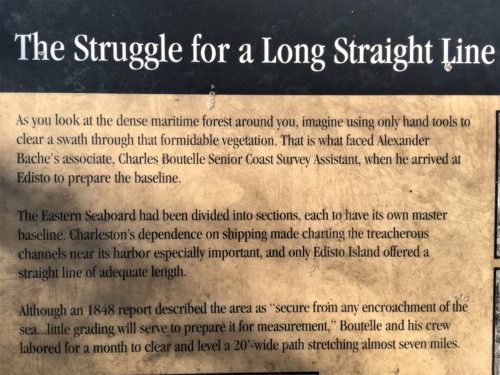

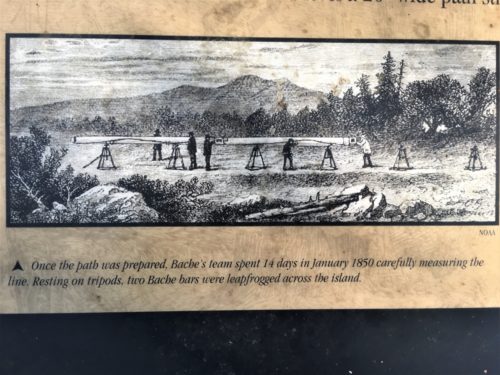

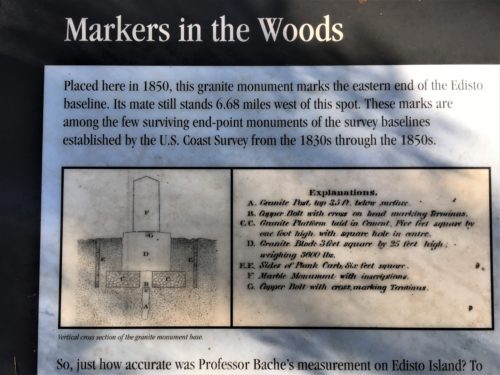

But then, for something totally unexpected . . . we ran across a trail sign pointing us to Bache Monument. Now we knew the name from our visit to the Edisto Research and Environmental Center the other day. We also knew we were a long ways from that monument. So what could this possibly be?

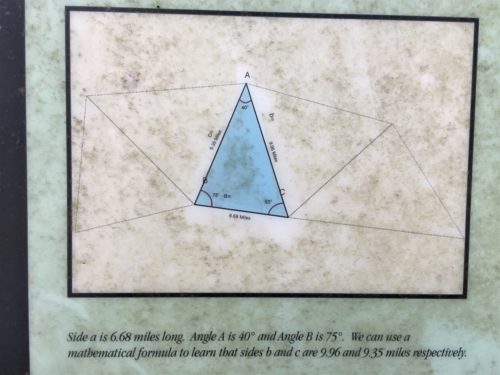

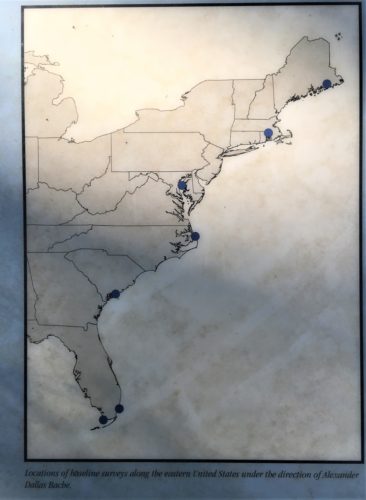

Though overgrown, it was a really neat discovery! It turns out that the Bache Monument is in both places! They’re not monuments like we thought – you know, grave markers – they’re monuments that mark this surveying milestone you’re about to read about. And now, we’ll have to return to the one we skipped the other day and check it out. 😊

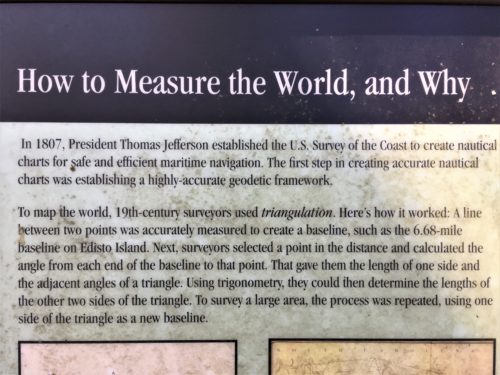

Did you catch that he’s Benjamin Franklin’s great grandson?

And West Point roommate to Jefferson Davis?

How cool is that!???

This is the marker

Here’s more information on this incredible man taken from the University of Pennsylvania archives:

Alexander Dallas Bache was born in Philadelphia, July 19, 1806, the son of Richard Bache, Jr. (1784-1848) and Sophia Burrell Dallas Bache (1785-1860). He was also the nephew of Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-1798), the grandson of Richard and Sarah Franklin Bache, and great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin.

Alexander Dallas Bache received his education at the United States Military Academy, graduating with the Class of 1825. After his graduation he was appointed Lieutenant of Engineers, but because of his teaching ability he was also selected to fill the position of Assistant Professor of Engineering at West Point. During these first years after his college graduation, he was also given charge of the construction of Fort Adams at Newport, and it was at this place he met his future wife, Nancy Clarke Fowler.

Professor Bache was appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy and Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania in 1828, which position he held until 1836. During this time he became associated with the Franklin Institute and contributed constantly to its Journal; he conducted extensive experiments and observations in physics and meteorology and won renown for his research on the subject of boiler expansion.

Upon the foundation of Girard College Bache was chosen its first President, and went to Europe to study the various school systems there. The funds for the erection of the College not being available at his return, Professor Bache became President of the Central High School of Philadelphia. During 1841-1842 he served as Superintendent of the Philadelphia Public Schools and also directed a magnetic and meteorological observatory, under the auspices of the American Philosophical Society, of which he was a prominent member.

In 1843 Bache returned to his Chair of Chemistry at the University, but after one year he resigned to accept the position of Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey. Under his able direction, the Survey at once became practically valuable; during the Civil War the Survey provided vital assistance, especially in 1863 when Bache was Chief Engineer in charge of the defense of Philadelphia.

In addition to his other duties he was one of the incorporators of the Smithsonian Institute, serving as a member of its Board of Managers until his death. Professor Bache was Vice-president of the United Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, and President of the American Philosophical Society, the American Philosophical Association for the Advancement of Science and the National Academy of Sciences. He was an honorary member of the Royal Society of London, the Royal Academy of Turin, the Imperial Geographical Society of Vienna and the Institute of France. The degree of Doctor of Laws was conferred upon him by the University of New York in 1836, by the University of Pennsylvania in 1837 and by Harvard University in 1851.

He was the author of many papers on scientific subjects, his main work being his Observations at the Magnetic and Meteorological Observatory at Girard College, published in three volumes, 1840-1847. He left $42,000 in trust to the National Academy of Sciences, the income of which is to be devoted to physical research. He died in Providence, Rhode Island, February 17, 1867.

Back out on the trail searching for Indian Point.

Hunter’s stand . . .

Look! Resurrection Ferns on a Live Oak tree!

Remember those from last year?

Well, here it is.

Indian Point.

Not quite what we were expecting to see. But then again, what exactly were we expecting??

You can easily get turned around on these trails in here. We suspect they’re more for hunters to use, than hiking trails. But we managed to get in a few miles before hunger began to overtake us and we headed back to the Jeep to find a good spot for lunch.

I just couldn’t get over the size of this Magnolia Tree!

It’s gi-normus!!

This used to be a barn.

In 1977, they accidentally caught it on fire during an agricultural burn. Ooops . . .

Large equipment storage across the street from the barn.

And boy did we! Not only did we have a nice view, but it came with entertainment as well!

We’re at Jacob’s Lake. Not sure if it’s the illegal one or not, but I highly doubt it. At any rate, it’s a fairly good sized body of water.

The entire time we were there, we watched the pelicans fishing – up close and personal! It was great fun! Wonder if they’d of come even closer if we’d had tuna today? 😊

There were two who were doing synchronized diving, but of course, once Blaine started filming them, they stopped. : (

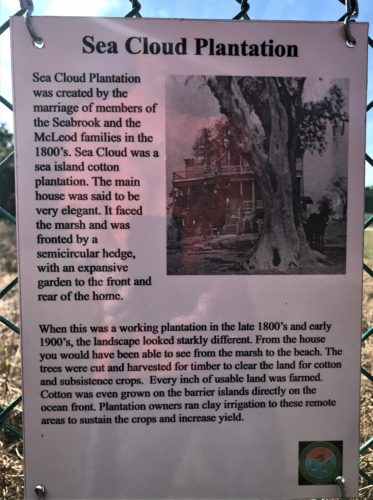

Next (and last) on our driving loop trail, was the remains of the Sea Cloud Plantation house. That’s a much better name, don’t you think?

Poor lighting made for poor pictures. : (

At least the Jeep had the right lighting! : )

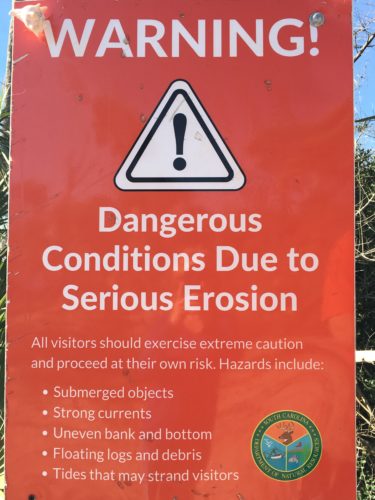

And then there was this sign . . .

It was just about high tide now, and I suggested we re-visit the beach, where we found a great place by the entrance to sit and watch the ocean. Ahhhh . . . . By the way – – that was about the only place that wasn’t under water. 😊

The first two pictures show the water level (and the lighting!) from our first visit to the beach today, and our second.

After . . .

When we finally managed to tear ourselves away, we still had more adventure waiting for us on the beach trail!

We heard (and saw) rustling in the brush to our right.

And look what was in there! An armadillo!

Once it finally realized we were there, you should have seen it ‘walk on water’ to get away! Haha!

We ended our spectacular day with a sunset walk on our own beach.

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas!