Now there’s a topic I’ll bet you never expected to see on our blog. Prostitution. But it’s so ingrained into Galveston’s history that I could hardly disregard it. There are companies here that offer $25 tours of Galveston’s historic and famed Red Light District. We did not take the tour. Are you breathing a sigh of relief? But we did try to walk down the 5 blocks of Postoffice street where vice reigned for over 70 years (What I found on-line is that those five blocks ran from 25th-29th street), but that part of Postoffice Street was blocked by an electrical sub-station, so I’m not sure where the tour goes . . . Since we didn’t take the tour, I did some research.

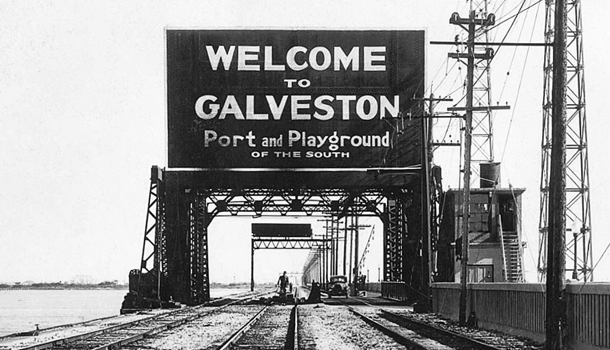

The Galveston of the past is vastly different from the family tourist destination the island is today. For at least a century, prostitution and gambling were openly tolerated by city officials. Because of the island’s acceptance of vice it was known by several nick-names over the years – Open City, Island of Illicit Pleasures, Sin City of the South and the Free State of Galveston.

Galveston had beautiful and elegant Victorian Mansions, built before the Civil War. When the downtown business district was expanded by the Union Army, Postoffice Street was split in two and the houses between 25th and 29th on Postoffice declined in value and became less desirable. They were readily snapped up by the shrewd madams of New Orleans who knew a bargain when they saw one. Close to the port and downtown business districts, these elegant but worthless houses were in an ideal location. The houses were uniformly painted white with either green or grey shutters as a shrewd marketing device by the madams. The higher-end and elegant houses were located directly on Postoffice Street. The alleys and cross streets were lined with “cribs” where sex could be had for a quarter. (In 1913, that’s $6.50 today. 1913 is as far back as the inflation rate calendar goes. But in 1929, it’s the equivalent of $3.76.) By 1929, there were 55 houses of prostitution on Postoffice street alone, providing employment for nearly 900 prostitutes.

In the early 20th century, Galveston’s official and unofficial leaders sought to manage prostitution by limiting it to a few blocks known as “The Line”, and essentially “looking the other way.”

During the early to mid 1950s, some of the late era’s most prominent men could be found frequenting Galveston – including the early years of the Rat Pack which included Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., and Dean Martin to name a few.

Galveston’s red light district lasted for over 70 years as a uniquely successful industry because of the combination of social and economic conditions on the island.

One of the factors that contributed to the longevity was the existence of The Mob who controlled the booze and gambling. Prostitution, alcohol and gambling were tolerated on the island because it filled the hotels. 2% of the population worked directly for the mob, 20% worked indirectly. The only rules were mob rules.

The prostitution trade was always separate from the alcohol and gambling, and it thrived and became an important part of the economy. Mary W. Remmers, in her short study of Galveston prostitution, “Going Down the Line,” writes that in the 1940s houses earned between $15,000 and $20,000 a week – or between $240,000 and $350,000 a week today.

And lest you think that this only went on in Galveston, it didn’t.

World War I was barely over when prostitution entered a new phase, marked by the persistence of red-light districts and traditional bawdy houses yet also by the increasing frequency of other forms of prostitution. During the 1920s and 1930s it became more common for prostitutes to work in hotels, apartments, and rooming houses and to communicate with customers by telephone. Prostitutes also adapted to the automobile by cruising the streets for clients, arranging with taxi drivers to supply customers, and working in roadhouses that sprang up just outside city limits. Red-light districts operated in a variety of cities and towns during the 1920s and 1930s, among them Beaumont, Borger, Corpus Christi, Corsicana, Dallas, El Paso, Galveston, San Angelo, and San Antonio. Galveston came closest to maintaining the turn-of-the century vice district; more than fifty Anglo brothels and at least two Hispanic brothels, housing a total of more than 300 prostitutes, were in operation there in 1929; 150 to 200 black prostitutes worked in houses and cribs on adjacent streets and in the alleys. In all, Galveston had some 900 prostitutes in 1929. Higher-priced prostitutes abandoned the district to operate as call girls in hotels, and many of the larger brothels closed down. Wretched slum housing, violence, and petty crime proliferated. The Great Depression brought additional women into the trade, drove down prices, and left many prostitutes on the edge of survival. By the late 1930s hundreds of low-priced prostitutes, charging from $.25 to $1.50, walked the streets and solicited from their jerry-built, one-room cribs. In the city as a whole in 1939 there were at least 2,000 prostitutes. Roughly 40 percent were Hispanic and 40 percent Anglo.

By far the most infamous center of prostitution in Texas during the years after WWII was Galveston. “If God couldn’t stop prostitution, why should l?” queried the mayor of Galveston who held the post from 1947 to 1955. The mayor wanted Galveston wide open, and so did his allies and supporters, among them the city’s powerful racketeers, the graft-ridden police department, and much of the citizenry, who believed that the local economy depended on maintaining a reputation for unimpeded gambling, drinking, and prostitution.

Some of the most successful women in Galveston were the madams. Rising through the ranks, most were former prostitutes who saved their money for old age…25 years! They bought or leased houses and would only entertain certain visitors or distinguished guests in their private parlors. The madams had working relationships with the politicians, police, pimps and gangsters. Extremely shrewd, they could navigate their way through the myriad of demands placed upon them. Some retired as millionaires and took their place in “proper society”.

One of the more notorious and successful madams was Mary “Gouch-Eye” Russel, who ran a bordello for over two decades, partnering with the mayor whenever he needed a special girl for a visiting big-shot. His gratitude was repaid when she would be tipped off to law enforcement house raids, which were mostly for show only. Within the boundaries of “The Line”, bordellos served johns and kept prostitution off the streets. At their peak in the 1940s, some houses could earn as much as $20,000 in a week.

Women came from all over the country because Galveston was where the money and the action was, but only the beautiful stayed due to fierce competition. The “soiled doves” as they were known, had a schedule to keep – every 15 minutes – up to 25 clients a night. They worked three weeks on and one week off during the hours of 6pm till 2am unless otherwise by appointment. And they were required to take a bath three times a week. They could earn up to $450 per week ($4,000 in today’s money), but from that, they paid rent and 40% commission of all her fees to her Madam.

Constantly subjected to harassment by the police, venereal disease and violence, it was no easy life. Despite the high wages, suicide was prevalent, often as a result of drinking mercury to induce abortion. Those considered less attractive eventually migrated to the Wild West.

With advancing age (25 years old!) they were required to move to the lower-end houses where the wages were reduced significantly.

In 1955 a leading national anti-prostitution organization branded Galveston the “worst spot in the nation as far as prostitution is concerned.” Anti-prostitution forces encountered less resistance in other towns but still found their job a difficult one. When civic and religious groups, newspaper editors, and representatives from nearby military bases and national anti-prostitution organizations turned on the pressure, police chiefs and other city officials pleaded a shortage of policemen, difficulty getting convictions, and weak county law enforcement that permitted unchecked vice just outside the city limits. Often underlying ineffective law enforcement were strong political pressures to go easy on vice, payoffs to policemen by vice interests, and faint public support for repression. Nevertheless, proponents of repression made significant headway during the 1950s. They publicized flagrant conditions, generated public concern, and joined forces with cooperative political and law-enforcement officials, including a number of police chiefs. In 1957 they gained a powerful ally in Texas attorney general Will Wilson, whose office led the way in breaking the back of the Galveston racketeers. Legal and media pressure forced many brothels to close and set the volume of prostitution on a downward course that continued into the 1960s.

Ruth Kempner married into one of Galveston’s most prestigious families. She had progressive and pragmatic views that sex workers would ply their trade no matter what, so why not have a little oversight by the cops? Never a prissy or hypocritical Victorian, Kempner stood up to conventional thinking as an advocate for prostitutes. She was also fearless, standing up to corrupt law enforcement officials, who profited from shaking down underworld figures, madams, and even the prostitutes themselves. In 1961, her endorsement from one of the most prominent madams of the day, probably won Kempner her election to City Council – the first woman to do so.

November 26, 1917 – June 16, 2008

And that’s most likely more than you wanted to know about prostitution in Galveston. 😊