Much of the information below was taken from npr.org:

This is how the article began…… Thursday is the last day of the official 2017 hurricane season. It’s been the most destructive year in recorded history, according to the National Hurricane Center, causing what may turn out to be more than $200 billion in damages. It’s also the first time that three Category 4 hurricanes have hit the United States in the same year.

For all the ruination in Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, at least Americans could see the hurricanes coming. TV networks covered the storm tracks exhaustively. But what happens to an American city when a hurricane strikes without warning?

The grandest city in Texas

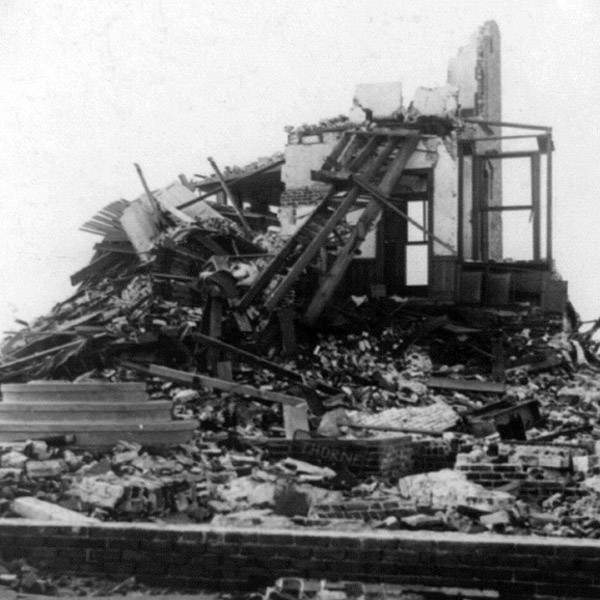

The Great Galveston Storm came ashore the night of Sept 8, 1900, with an estimated strength of a Category 4. It remains the deadliest natural disaster and the worst hurricane in U.S. history – destroying more than 3,600 buildings with winds surpassing 135 miles per hour.

From 6,000 to 12,000 people died on Galveston Island and the mainland. Texas’ most advanced city was nearly destroyed.

Forecasting was primitive in those days — they relied on spotty reports from ships in the Gulf of Mexico. Citizens of Galveston could see that a storm was brewing offshore, but had no idea that it was a monster.

“Everyone went about their usual tasks until about 11 a.m. when my brother, Jacob, and our cousin, Allen Brooks, came from the beach with the report that the Gulf was very rough and the tide very high,” remembered Katherine Vedder Pauls, not quite 6 years old at the time. Her oral history and others used for this report are archived at Galveston’s Rosenberg Library.

“About half past 3,” she continued, “Jacob and Allen came running, shouting excitedly that the Gulf looked like a great gray wall about 50-feet high and moving slowly toward the island.”

At the dawn of the 20th century, Galveston was the grandest city in Texas. It could boast the biggest port, the most millionaires, the swankiest mansions, the first telephones and electric lights, and the most exotic bordellos. After the 1900 storm, she would never regain her status.

“No tongue can tell it!”

What became of the people of Galveston is the story of what happened before accurate weather forecasting, mandatory evacuations, and storm building codes.

“We knew there was a storm coming, but we had no idea that it was as bad as it was,” said William Mason Bristol, who was 21 when he rode out the storm in his mother’s boardinghouse. “You see, we didn’t have a weather bureau that give us the dope that they got now…They had no airplanes to go up there and see how bad it was.”

The hurricanes of 2017 were destructive in terms of dollars, but the official death toll remains well under 300. In 1900, thousands died.

The unnamed hurricane swept in from the Gulf with an estimated tidal surge of 15 feet, so high that it swallowed the skinny barrier island that was only 5 feet above sea level.

“Oh, it was a awful thing. You want me tell you, but no tongue can tell it!” recalled Annie McCullough. She was about 22 years old in 1900. Her family was on a mule-drawn wagon trying to escape the rising tide.

“The water was comin’ so fast. The wagon gettin’ so it was floatin’. The poor mules swimmin’ that was pullin’. And the men laid flat on their stomach, holdin’ the little children.”

Survivors wrote of wind that sounded “like a thousand little devils shrieking and whistling,” of 6-foot waves coming down Broadway Avenue, of a grand piano riding the crest of one, of slate shingles turned into whirling saw blades, and of streetcar tracks becoming waterborne battering rams that tore apart houses.

“The animals tried to swim to safety and the frightened squawking chickens were roosting everywhere they could get above the water,” Pauls remembered. “People from homes already demolished were beginning to drift into our house, which still stood starkly against the increasing fury of the wind and water.”

At the height of the storm, John W. Harris remembered two dozen terrified people climbing in through the windows of their home on Tremont Street. His mother prepared for rising floodwaters by lashing her children together.

“Mother had a trunk strap around each one of us to hold onto us as long as she could,” he recalled.

Rosenberg School, built of brick, became a refuge for Annie McCullough’s family and many others.

“The people was screamin’ and hollerin’ and so, huntin’ their folks,” she said in an oral history recorded by her grand-niece, Izola Collins. “The wind! Those men that was in the school, all they could do was stand against those doors and hold ’em.”

The single most heart-wrenching tragedy happened to St. Mary’s orphanage. Ten Catholic nuns from the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word and 90 children died when fearsome waves destroyed two wooden dormitories, that were built close to the beach in the belief that ocean breezes would reduce the danger of yellow fever. The sisters tethered the orphans together with clothesline. That’s how they were found the next day, drowned. Only three boys escaped.

“A terrible time”

The storm began to subside about daybreak. The sun rose on Sept. 9 on a coastal city obliterated. One survivor described “knots of people frightened out of their wits, crazy men and women crying and weeping at the tops of their voices.”

Corpses were everywhere. Authorities declared martial law and began to force men — most of whom were black — at bayonet point to collect the dead, pile them on barges, and dump them in the Gulf for burial. But the cadavers washed back onshore. Finally, they had to be burned in funeral pyres. There were orders to shoot on sight the “ghouls” who stole jewelry from the tangled bodies.

“It was a terrible time, it really was,” recalled Louise Bristol Hopkins, who was seven. “I heard the stories of women with long hair who had been caught in the trees with their hair and cut to pieces with slates that had been flying.”

Katherine Vedder Pauls recollected a ghoulish incident that happened to her mother.

“She stepped on a barrel concealed by the water. It rolled and she went under with it. She grabbed at something to pull herself up. It was the body of a small girl. Her self-control gave way and she wept hysterically.”

Harris, who became a prominent banker and philanthropist on the island, lost 11 relatives in the 1900 storm. He remembered the next morning his family was having breakfast in their house, that withstood the waves, when the mayor came by.

“He said to father, ‘John, your whole family are destroyed.’ And I remember it’s the first time that I ever saw father with tears in his eyes. He had no idea of the extent of the damage. We hadn’t left the house yet.”

rescuers would go on to find 80 bodies amid the rubble.

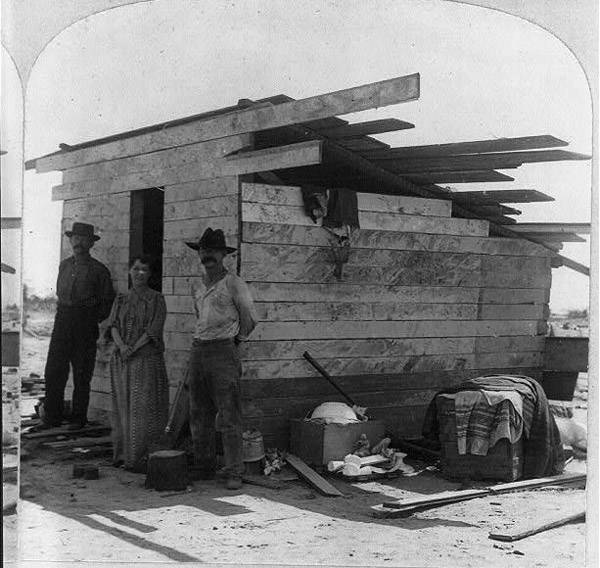

constructed with what lumber was available in the days after the storm.

In the years after the horrific storm, Galveston reinvented itself in a burst of municipal determination. The US Army Corps of Engineers constructed a 17-foot seawall. The city undertook an ambitious “grade-raising.” Two thousand surviving structures — from shanties to a massive Catholic church — were jacked up and sand pumped underneath. Both the seawall and the grade-raising were regarded as engineering marvels of their day.

The biggest change I can see is no more rocks. Wonder why?

This picture’ll show up again in the January 11th post. : )

For decades, people on Galveston Island never spoke of the 1900 storm. “The folks that survived the storm were sort of like people who survived a war,” recalled former state Sen. Babe Schwartz, a legendary Galveston figure. He was interviewed in 2000.

“No chamber of commerce wants to talk about the worst tragedy in the history of the United States where 6,000 to 8,000 people died on this little ol’ island.”

Facts about the 1900 Storm:

• 8.7 feet: The highest elevation on Galveston Island in 1900.

• 15.7 feet: The height of the storm surge.

• 28.55 inches: Barometric pressure recorded in Galveston, 30 miles from where the eye of the storm is best estimated. At the time, this was the lowest barometric pressure ever recorded.

• 6,000 to 12,000: Number of people estimated to have died during the storm. 20% of the island’s population.

• 30,000: Number of people left homeless.

• 37,000 people: Population of Galveston in 1900.

• 3,600: Number of buildings destroyed by the storm.

• 130 to 140 miles per hour: Speed meteorologists estimate the winds reached during the storm.

• $20 million: Estimated damage costs related to the storm. In today’s dollars, that would be more than $700 million

It remains the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 suffered the loss of 1,200 people.

Beginning in 1875, residents proposed a seawall be constructed to protect the city. The chief meteorologist at the Galveston Weather Bureau dismissed the concerns, saying that it would be impossible for a hurricane of significant strength to strike the island.

Due to the destruction of telegraph lines and bridges to the mainland, news of Galveston was not able to reach the mainland until six messengers from the city reached Texas City at 11 a.m. on September 9 through Pherabe, one of the few ships to survive the storm. Rescuers arrived to find the city completely destroyed. Survivors set up temporary shelters in surplus U.S. Army tents along the shore. The first post-storm mail reached Galveston on September 12 and by September 13, basic water service was restored. Within three weeks, cotton was again being shipped out of the port.

Within two years, in order to prevent this kind of disaster again, Galveston was raised by as much as 17 feet (5.2 m) above its previous elevation. More than 2,100 buildings were raised in the process. Galveston was tested by a 1915 hurricane of similar strength. 53 people lost their lives, a number significantly less than the death toll of the 1900 hurricane. In 2001, the Galveston Seawall and raising of the island were named jointly as a National Historical Civil Engineering Landmark.

Along with building a seawall, Alfred Noble, Henry M. Robert (author of “Roberts Rules of Order”) and H.C. Ripley (engineers) recommended the city be raised 17 feet at the seawall and sloped downward at a pitch of one foot for every 1,500 feet to the bay.

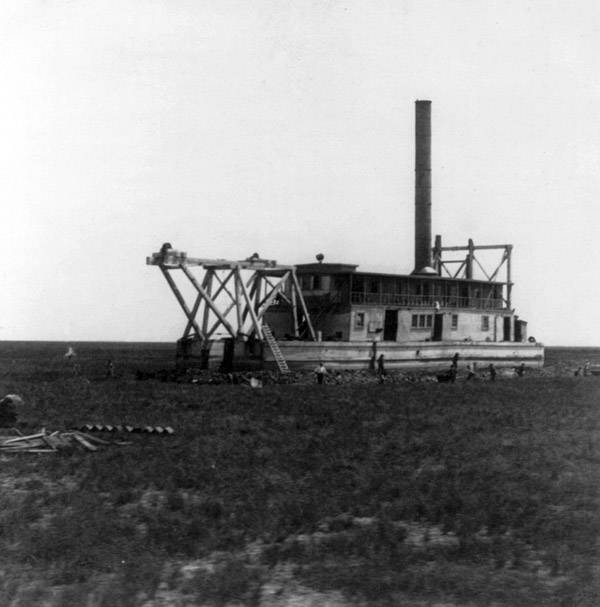

The first task required to translate their vision into a working system was a means of getting more than 16 million cubic yards of sand – enough to fill more than a million dump trucks – to the island.

The solution was to dredge the sand from Galveston’s ship channel and pump it as liquid slurry through pipes into quarter-square-mile sections of the city that were walled off with dikes. Their theory was that as the water drained away the sand would remain.

Before the pumping could begin, all the structures in the area had to be raised with jackscrews. Meanwhile, all the sewer, water and gas lines had to be raised. Some people even raised gravestones and some tried to save trees, but most of the trees died. In the old city cemeteries along Broadway, some of the graves are three deep because of the grade raising.

The city paid to move the utilities and for the actual grade raising, but each homeowner had to pay to have their house raised.

By 1911, 500 city blocks had been raised, some by just a few inches and others by as much as 11 feet.

In 2001, the Galveston Seawall and raising of the island were named jointly as a National Historical Civil Engineering Landmark.

that killed 6,000 to 12,000 people — the worst natural disaster in U.S. history.

I don’t know where this is, we never saw it.