Catalina State Park, Tucson, Arizona

Peace I leave with you; My peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid. ~ John 14:27

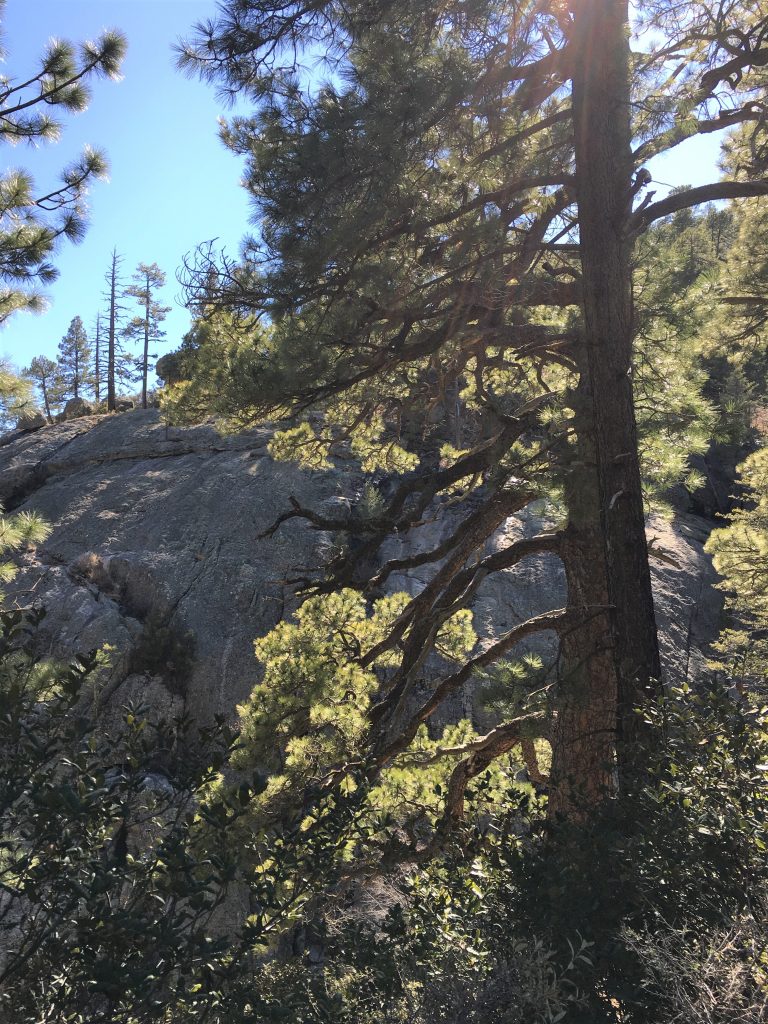

It promised to be yet another gorgeous day today, clear skies, nice temperatures, slight breeze every now and again, mid-seventies . . . . Of course, that’s down here in the valley. Where we’re headed, it promises to be 20-30 colder. In actuality, it turned out to be 27.

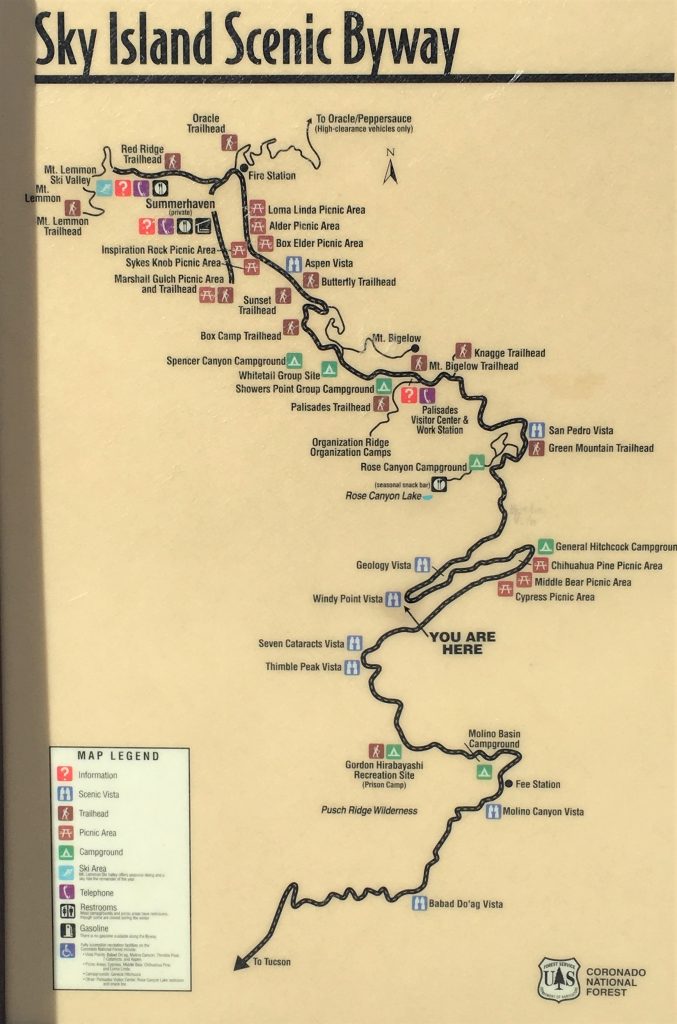

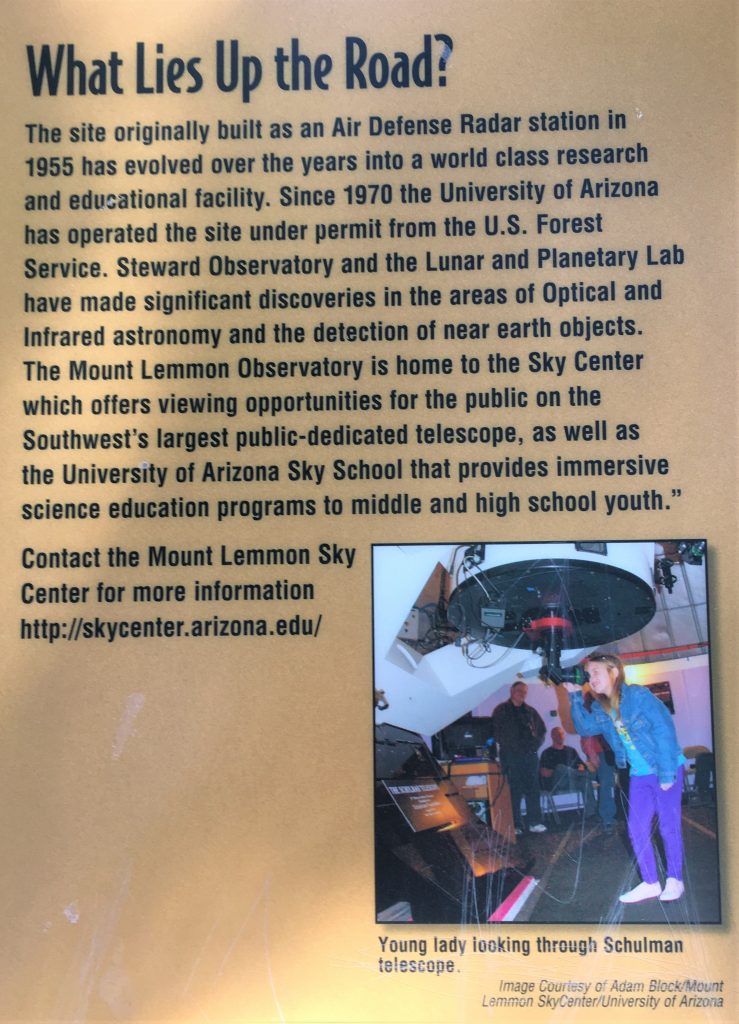

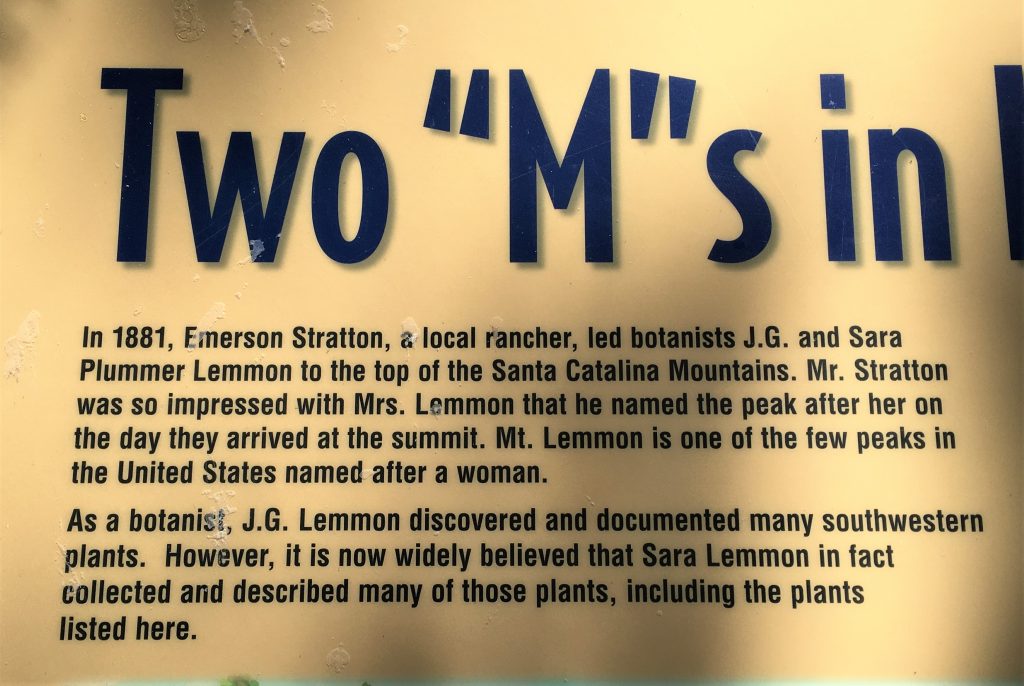

Today we took on a scenic drive in order to get to the top of Mt. Lemmon. With an elevation of 9,159-feet, Mt. Lemmon is the highest peak in the Santa Catalina Mountains. (I read somewhere that we were at 9,600+, but that must have been an unreliable source I looked at briefly. Either that, or my mind added the 1 & 5 together without my knowledge and came up with 6. Good if you’re doing math, not so good if you’re reading. 😊)

The only problem with visiting the mountain from here? You can’t just drive from here to there. You have to go 56 miles in order to go 8. Crazy! We can see Mt. Lemmon from our campsite just 8 miles away.

One of the signs that caught my attention along the way was a small roadside sign that said, “Snake Avoidance Training Classes For Dogs”. Now that’s something you don’t see just anywhere! 😊

It was a wonderfully scenic drive! Just remember that most of the drive pictures were taken out the windshield, so if you see ghost-like features, it’s just sun glare. 😊

And one other thing before we really get started. I’m saving one of our stops to the top until later for dramatic effect. 😊

We were shocked!

Especially given that the elevation change on this road is 7,000′ in 30 miles!

Not sure they even observe the 35pmh speed limit!

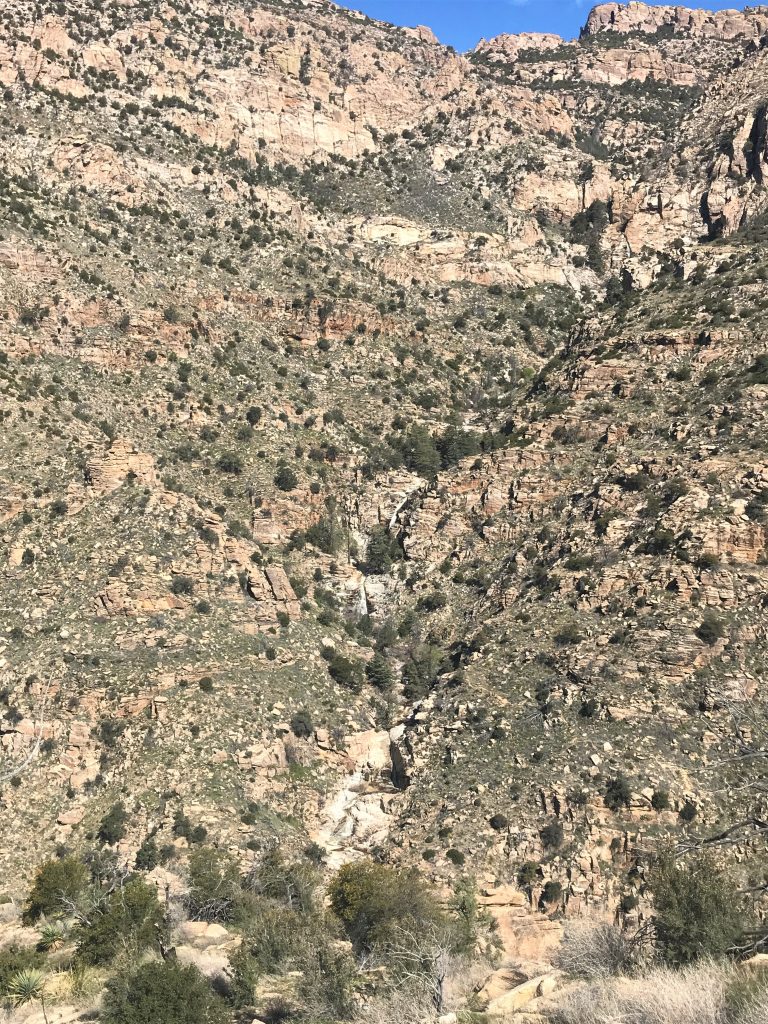

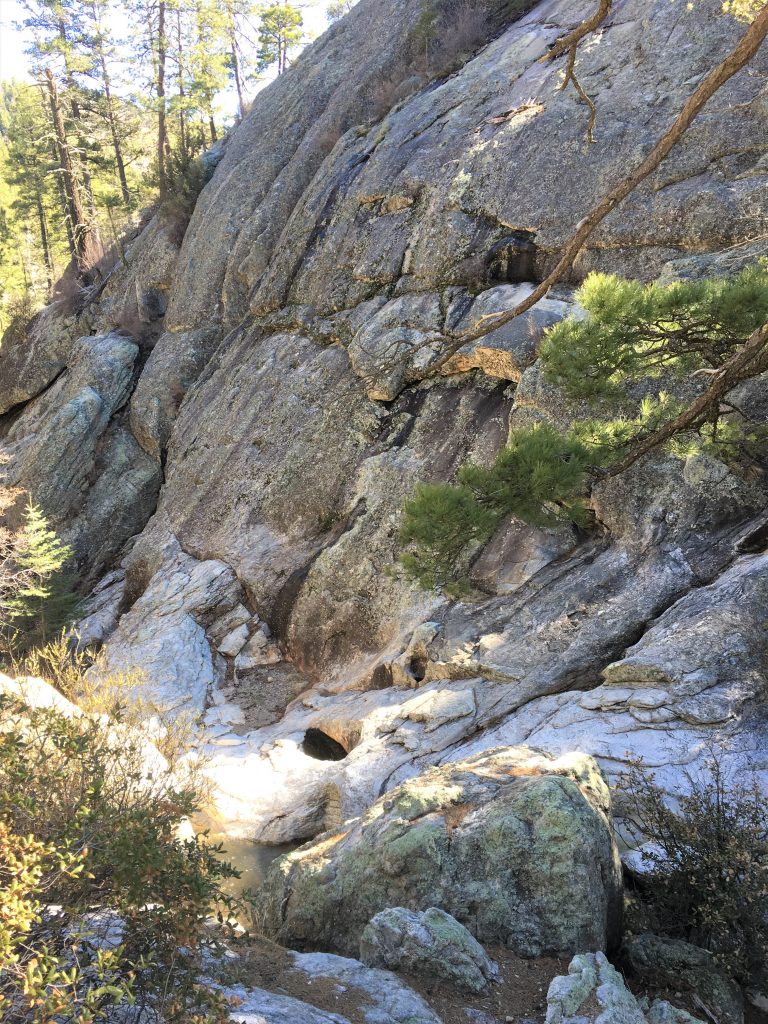

See the waterfall?

Great picture!

There were actually three of them.

Let’s hope no one needs that today!

Summerhaven, est. 1939

but the trees were dropping ice on them. : )

We had to eat lunch in the Jeep. : (

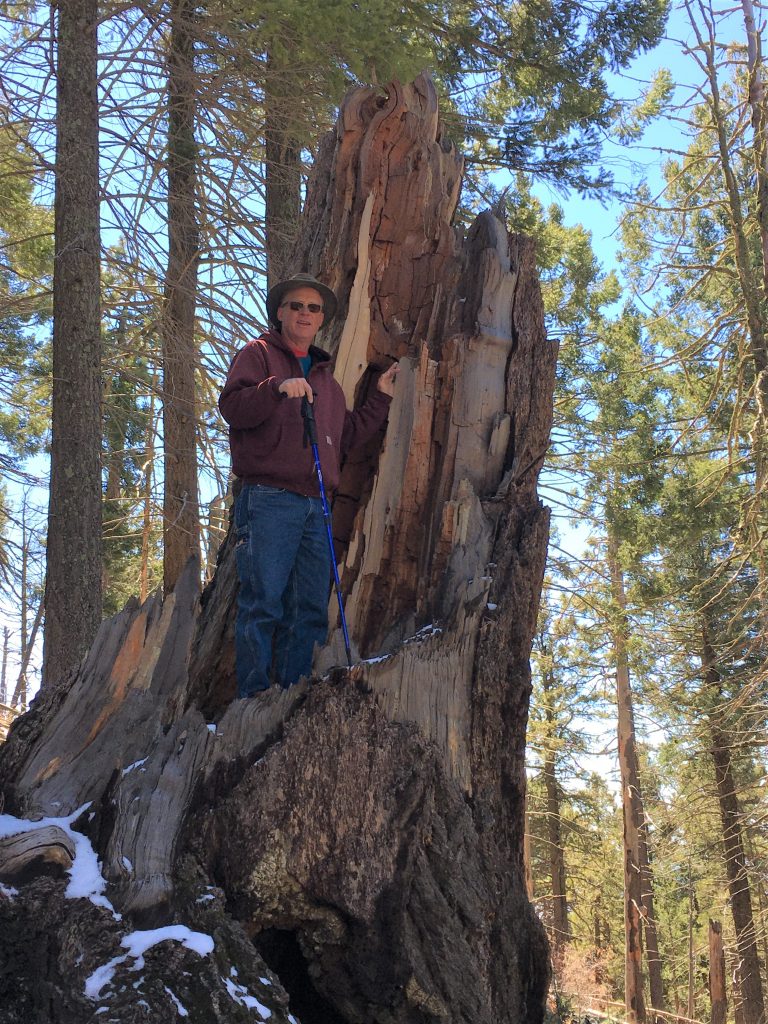

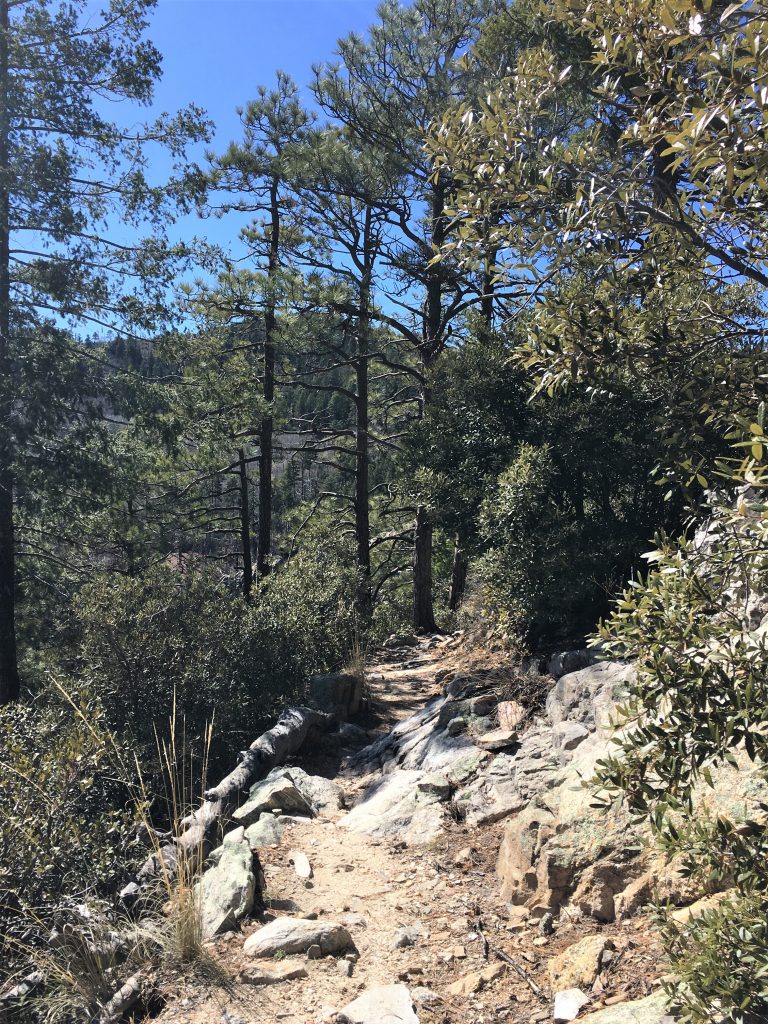

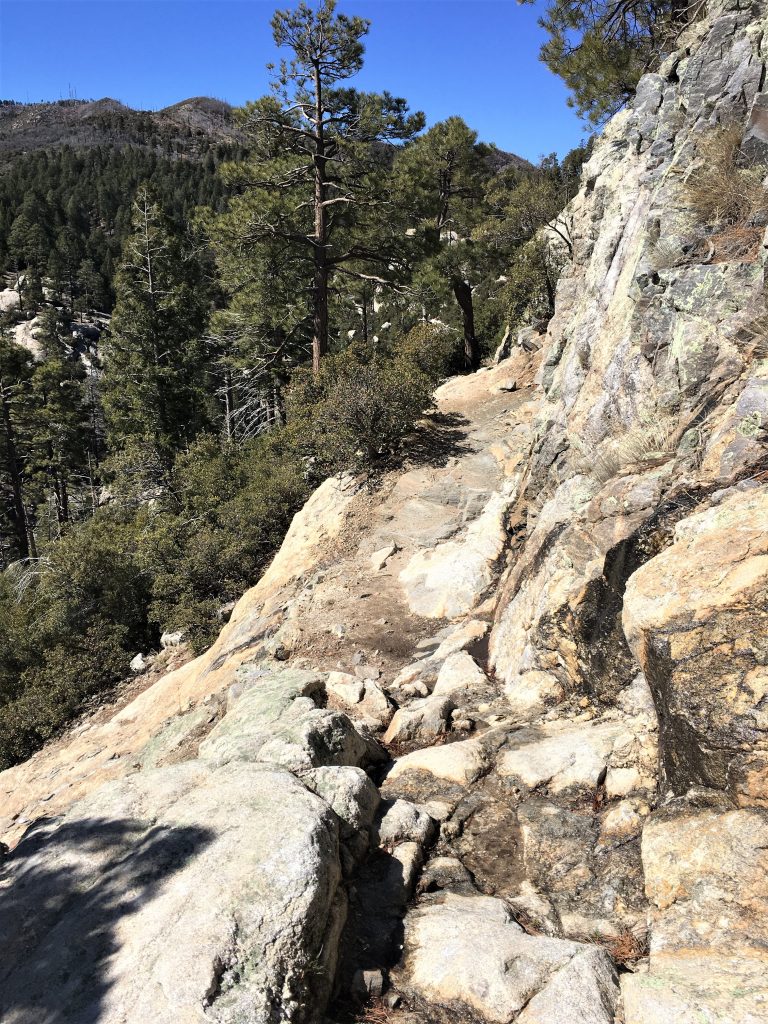

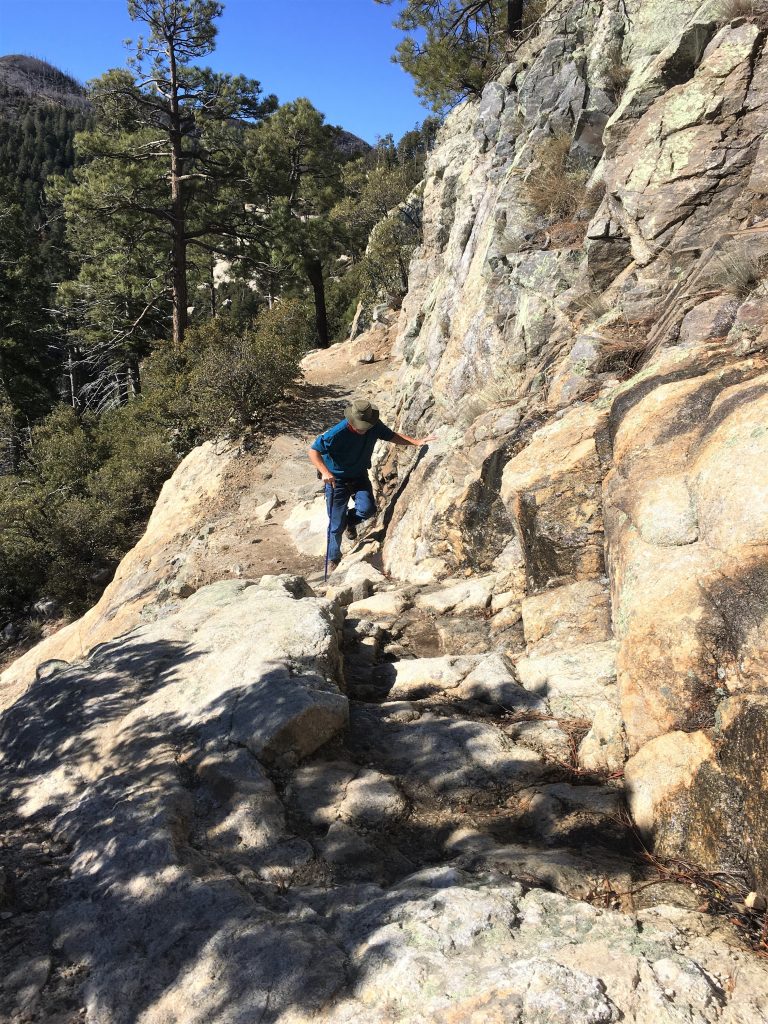

Once we got to the top, or as near as we were permitted to go, we eventually found the trail head for a short hike up here – – after asking a local couple to help us out.

We’ve finished our walk around the top and are headed back down the mountain a bit.

Here’s where we back up a little before moving on. . . .

Near the top, we had made a short stop at the small Visitor Center run by the National Park Service to try to garner information about any trails that may be up here. There was one woman working behind the counter and as soon as we entered the building, she stood and moved about 10 feet away from the counter. I suppose given the times, that’s understandable. We asked her about hiking and told her that we’d just completed two days of strenuous hiking, so we were looking for something fairly easy today.

She sent us to the Sunset Trail.

Just wait! You’ll see what I mean!

It was a real log cabin, rather than the wood ones we’ve been seeing.

What a view!!

It was sooo pretty! Too bad the picture doesn’t show it. : (

Pieces that flaked off from the rocks.

Sooo pretty!

I see a lot of pony tails and clip-ups in my future . . .

He did it much easier than I did. : )

I don’t know . . . . maybe the woman at the Visitor Center was so far away, she didn’t hear us . . . .

This certainly didn’t qualify as “fairly easy” in our book.

We were curious about how this twisty-turny-on-the-edge-sometimes-road was built, but there was nothing at the visitor center to help us. And the woman there certainly didn’t seem like she’d be interested in satisfying our curiosity, so I found the following on-line:

A popular Mount Lemmon recreation site for rock climbers nicknamed Prison Camp pokes fun at the area’s history, with walls dubbed “Alcatraz” and “Jailhouse Rock.”

The names are harmless, but some people might not know the brutal punishment that the U.S. government inflicted on Japanese Americans in that same area less than a century ago. In that spot, just seven miles up the Catalina Highway in Tucson, stood a Japanese American internment camp established after Pearl Harbor during World War II.

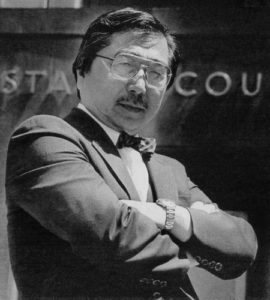

The historical site is officially named after Gordon Hirabayashi, a Japanese American civil rights activists and one of the many prisoners who served at the camp, where they were forced to work on the highway’s construction.

Hirabayashi was a senior at the University of Washington in 1942 when Pearl Harbor happened. He was one of only three Japanese Americans who brought lawsuits before the Supreme Court, making himself a political symbol during that time of war.

Still in college at the time, Hirabayashi ignored the first presidential order called the West Coast curfew, which required people of Japanese background to be home by 8 p.m.

“Why the hell should I go back? I’m an American citizen and I haven’t done anything wrong,” was a question that Hirabayashi often asked while out with friends, recalled Peter Irons, a professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego. The two knew each other in the 1980s after Irons found documents showing government misconduct during Hirabayashi’s original Supreme Court case. This would eventually help him be vacated of all convictions.

In fear of people from Japanese descent causing harm to the country, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the removal or any or all people “as deemed necessary or desirable,” even American citizens, and forced them to move eastward and into remote internment camps.

It’s known as the largest forced removal and incarceration in the U.S. history. More than 100,000 Japanese Americans were relocated to isolated internment camps.

Hirabayashi refused to register at a processing center and then turned himself into the FBI. He was jailed, but wouldn’t post the $500 bail. He remained in jail for six months awaiting his trial. Hirabayashi was found guilty of violating the court orders and was sentenced to serve three months at the internment camp on Mt. Lemmon.

The government refused to pay for his fare to get to Arizona, so he hitchhiked to the camp. When he arrived, the guards couldn’t find his papers and told him to go into town and see a movie while they looked. He took their advice, then headed back to camp to serve the three months. “A very honorable thing to do,” said Irons.

In the early 1980s, Irons began writing a book about the Japanese American internment cases, “Justice at War.” While reviewing the original case files, he discovered that the U.S. Solicitor General, the person appointed to represent the federal government, had knowingly lied to the Supreme Court in the original three Japanese American internment cases.

“I realized it might be possible to reopen their cases, even 40 years later,” Irons said.

In their original cases in 1942, the war department claimed some Japanese Americans had committed espionage. The FBI, however, found no evidence of this. The U.S. Solicitor General was informed of that fact, but ignored it. “The Supreme Court was misled,” said Professor Irons. “He knew what he was telling the court was not true, so that made the convictions, in a sense, illegitimate.”

After Hirabayashi’s case was taken to the Ninth Circuit, all convictions were finally vacated. “He was a very articulate person,” recalled Irons. “He looked like a college professor, talked like a college professor.”

Hirabayashi died many decades later in 2012, while living in Edmonton, Alberta. He was 93.

~ Tobey Schmidt, arizonasonoranewsservice.com

And this is what the Forest Service website says about it:

Though virtually everyone calls this road the Catalina Highway, it is officially designated the General Hitchcock Highway in honor of Postmaster General Frank Harris Hitchcock. He, perhaps more than anyone else, was responsible for bringing together all the elements necessary to construct this popular access route into the Santa Catalina Mountains. Work was begun on the road in 1933 and completed 17 years later in 1950. Much of the labor was supplied by workers from a federal prison camp located for that purpose at the base of the mountain.

Certainly a different tone than the article above . . . .

of the early road and then its construction.

And one more long article about the history you can read – – – if you’re interested in history. This one was published in May, 2019 and written by Tom Prezelski on TucsonSentinel.com

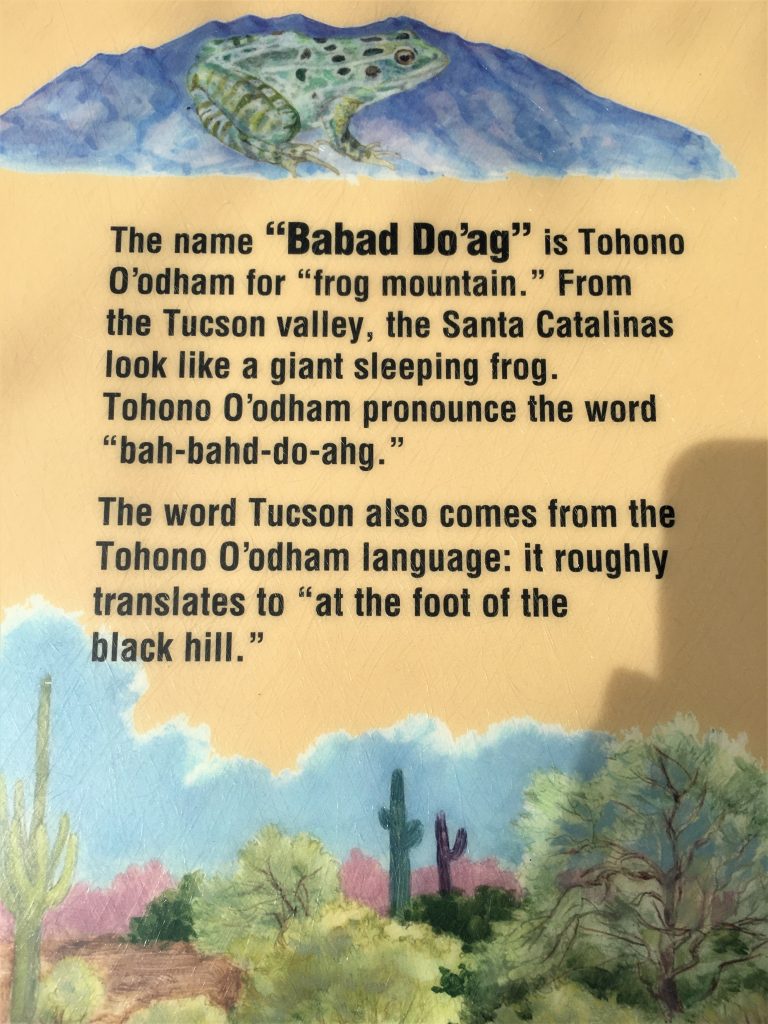

As summer approaches, Pima County residents look toward the Santa Catalina Mountains as a refuge from rising temperatures. Rising over 5,000 feet above the desert floor, the summit of Mt. Lemmon is typically 20 degrees cooler than the Old Pueblo. Yet, despite their obvious appeal as a retreat from the heat, the mountains next door remained largely inaccessible to Tucsonans until well into the 20th century when a colorful newspaperman dragged county and federal officials into pursuing an ambitious project to build a road up Mt. Lemmon.

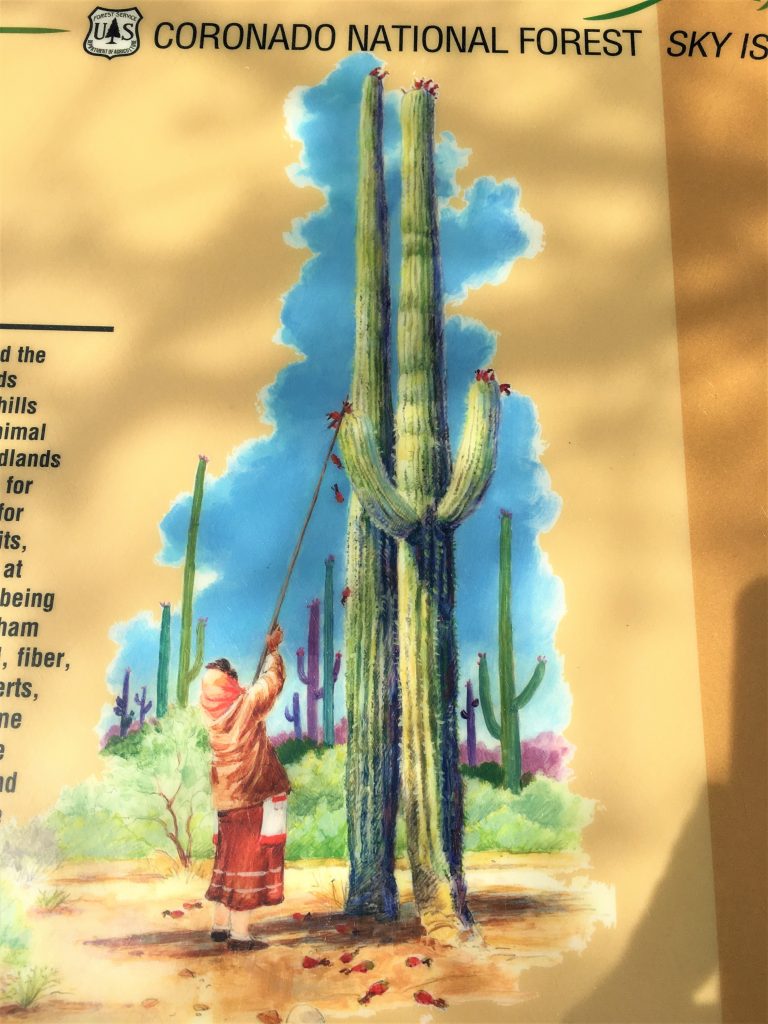

Before the 1930s, Tucsonans would usually approach the mountain from the north, via the mining camp of Oracle just over the line in Pinal County. This was the route taken by botanist Sara Lemmon when she ascended the summit in 1881, an achievement commemorated by Pima County Surveyor George Roskruge when he named the peak in her honor on his famous 1893 map. In 1920, the U.S. Forest Service improved this route — described as a “burro trail” — into a single-lane automobile road to service a small community, eventually known as Summerhaven, which had developed on top of the mountain.

The more rugged south face of the range was not entirely ignored. Sabino Canyon had long been a popular picnic site. Additionally, a handful of wealthy Tucsonans had located summer cabins at a place they called “Soldier Camp,” because troopers from Ft. Lowell had established a convalescent camp there in the 1880s. The route, accessible only by mule even in the 1920s, became known as Soldier Trail.

As travel by automobile became more popular nationally, the “Good Roads” movement emerged, calling for paved streets and highways. The federal government became involved in road construction and improvement as they never had been before. By the 1920s, in some parts of the country, roads were being built not for commerce, but for the express purpose of opening up areas to recreation.

Tucson resident and best-selling author Harold Bell Wright’s 1923 novel “The Mine With The Iron Door” contributed to increasing interest in the Santa Catalinas and accelerated notions of developing recreational access. Community leaders and the press called for building a road up the south side of the Catalinas with a road through Sabino Canyon. Advocates for the proposal said that this would keep tourism dollars that would otherwise go to California in Pima County. Initially reluctant, Board of Supervisors Chairman Carlos Ronstadt was persuaded by business community boosters to put the item before voters in a bond election in November 1928.

The community as a whole proved skeptical. Prominent local engineers from the University of Arizona and in private practices criticized the proposal as unworkable, unnecessary and poorly thought out. The Star editorialized that the project would only benefit “those who can afford vacation homes.” In the end, the item failed by a 2-1 margin.

The idea was soon revived by a new champion. “General” Frank Harris Hitchcock was a dapper and imperious Republican Party power-broker who had the ear of President Hoover and had served in various high-level federal patronage positions, including the office of postmaster general. Having been one of a partnership that purchased the Tucson Citizen in 1910, Hitchcock came to Tucson in 1928 to run the paper personally, where he proved to be a controlling, difficult and notoriously cheap boss.

Hitchcock took up advocacy for the new road after a bird-watching trip in 1930. After the earlier failure, county officials were leery, so he used his influence with Forest Service officials and convinced them to pursue the idea. The County’s support was still necessary to make it happen, so the Board passed a resolution in 1931 backing the proposal. Though early on it was understood that the county would ultimately be responsible for maintaining the road, the county engineer soon found himself sidelined by federal officials, prompting frustrated Board Chairman J.C. Kinney to say that the Forest Service “must skin their own cats” as the county would not contribute to the project’s planning or construction.

The Forest Service soon rejected the notion of running the road through Sabino Canyon, determining that a route via Molino Basin was more feasible. Given the nationwide economic crisis, potential costs became a concern. Hitchcock proposed, and helped arrange for, the use of convict labor to construct the highway — a controversial idea even at that time.

Construction began in 1933. A labor camp established near Soldier Camp became home for a rotating and eclectic mix of prisoners. At first these were minor offenders on loan from a federal prison in Texas. Many of them were Mexican nationals who had crossed the border illegally after a change in immigration policy during the Hoover administration. Later, after the United States entered World War II, their number included Hopi, Mennonite and Japanese-American draft resisters. The camp was supervised by former Pima County Sheriff Walter Bailey, who famously went back and forth in the 1923 Studebaker he had used while in office, a vehicle which is still on display at the Arizona Historical Society museum in Tucson.

Construction of the road proved slow and difficult. It would not be until 1945 that the road, largely unpaved at this point, would be formally dedicated. Pima County officials, perhaps no longer cranky about being cut out of the project, participated in the ceremony. The road, now called the Catalina Highway, was completed in 1950. Hitchcock, having died suddenly in 1935, was not around to see it, though a plaque memorializing him would be placed at Windy Point and some referred to the road as the “General Hitchcock Highway.”

Though county officials were marginalized from the project early on, they would remain responsible for safety and maintenance along the road. At various times, the road was regarded as one of the most dangerous in the state, presenting special challenges for the sheriff, though improvements in the 1980s and ’90s changed this for the better. Additionally, issues like rockfalls, ice and snow are a particular problem largely unseen in most of the county’s road system. However, to the hundreds of thousands of county residents for whom the winding road presents the promise of a respite from the desert heat, the added trouble and expense is well worth it.

I’ve just about come to the conclusion that I shouldn’t talk to my family while we’re driving. First of all, most of our close calls or accidents seem to be while I’m talking to my mother. Yesterday’s close call, being case-in-point. But then today on the way home, as I’m leaving a return message for my brother, a large swarm of big bugs flew straight into our windshield! They were so large we saw them coming, but it happened so fast, there was nothing to do except absorb the hit – – and the splatter. Gross!!

Later, just a few miles from home, I was exchanging texts with Blaine’s Aunt Sandi, when something else happened. We’d been sitting at a light, but when Blaine went to go, the Jeep didn’t want to. Sort of acting like a stubborn mule. Fortunately, just around the corner we were turning, there was a small strip mall and Blaine was able to coax the Jeep in there so he could check stuff out. Our texting time, became a time of prayer! And let me tell you, her prayers are powerful! We were able to make it the additional 10 minutes to home without issue, but something’s definitely rotten in Denmark! (that phrase actually comes from a line in Shakespeare’s Hamlet – back when people actually knew what was in Shakespeare’s plays. 😊)

At any rate, Blaine believes it’s either the transmission (smelled horrible!) or the front axle. Time will tell. Hopefully, we can find someone available to look at it, because neither of those are things Blaine can do himself. ☹

Oh! And to end our day? More drama! A spider who decided it wanted to shower with me, was eventually re-discovered and killed by my very own knight – – before I’d get back in again. I tried to do it myself, but by the time I got a Kleenex to do it myself, it had disappeared and I had to call in reinforcements.

And that’s how our lovely day ended, but the rest of it more than made up for the end! And of course, because it was still a clear evening, we watched the sun cast its glow upon the mountains in front of our picnic table.

Thank You, Father, for the beauty of the earth and for watching over us so well – in both large and small things!