Call it the Lawn Lake Flood, Alluvial Fan, the Flood of ’82, or just a catastrophic disaster, but whatever you do, don’t call it just a flood. This is one of those times where, I’m certain at least one of the Visitor Centers here in Rocky Mountain National Park has a display, but unfortunately, due to the COVID outbreak, we’re unable to check it out, so I had to do my own sleuthing.

Definition first. An “alluvial fan” is a fan-shaped mass of alluvium deposited as the flow of a river decreases in velocity. And now you need another definition! Unless you know what ‘alluvium’ is? 😊 Alluvium is loose, unconsolidated soil or sediment that has been eroded, reshaped by water in some form, and redeposited in a non-marine setting. Alluvium is typically made up of a variety of materials, including fine particles of silt and clay and larger particles of sand and gravel. In this particular case, it also included huge boulders and rocks. As the strength of the water dissipated, it gradually dropped off increasingly smaller rocks, trees and sediments.

I think I’ll put in the articles, and then the pictures at the end. It’s easier and less time-consuming, and right now, I’m all about saving as much time as I can. 😊

From the dam, the flood charged down the steep channel of Roaring River. The flood swept away one camper. It eroded areas up to 50 feet deep. After dropping 2500 vertical feet over 4.5 miles, the flood poured out into Horseshoe Park – a relatively flat basin. There it dropped its load of boulders and debris and created an alluvial fan of over 40 acres. A garbage truck operator observed the flood and called National Park personnel who began emergency response activities. The flood went out the east end of Horseshoe Park, filled and then overtopped a 17-foot-high concrete dam called Cascade Dam. The maximum overtopping was 4 feet. After 17 minutes of overtopping, Cascade Dam gave way and a new flood surge of 16,000 cfs poured through the breach.

Just below Cascade Dam was a campground. All campers had been evacuated, but two campers went back into the area and were drowned when the second flood wave arrived. The flood also destroyed a state fish hatchery.

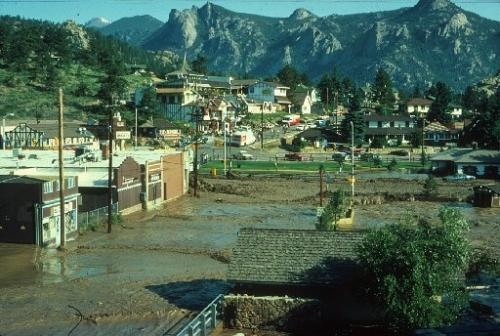

The flood swept motels, residential structures, and mobile homes off their foundations. In the town of Estes Park, debris-laden, muddy water up to five feet deep (6,000 cfs) poured through the business district. It damaged 177 businesses (over 90% of the businesses). Damages totaled $31 million and a total of three lives were lost.

The event was declared a presidential disaster. The National Park Service was sued for not having a warning and evacuation plan for a known, manmade hazard within the park and compensated a next of kin $480,000. ~ report on damfailures.org

From a NPS PDF:

Flood! In mountain environments weather patterns can change quickly turning meandering streams into scouring walls of water or flash floods. These awesome events can be natural or human-caused. In recent years there have been two major floods in or near Rocky Mountain National Park. The Big Thompson flood in 1976 was a natural disaster. The Lawn Lake flood in 1982 resulted from failure of a dam constructed in 1903. “I started to hear a sound like an airplane…there were loud booms…I saw trees crashing over and a wall of water coming down…there was a deafening roar… Steve Cashman, survivor of the flood of 1982.

The Big Thompson Canyon located east of the town of Estes Park has steep walls of bedrock and easily eroded soil. The night of July 31, 1976, a large storm system caused torrential rains over the upper section of the river. Water levels swiftly rose over nine feet, cut away much of the river banks ,and relocated the main channel. Soil, rocks, trees, homes, and businesses were swept downriver. Upon reaching the plains the water slowed, spreading debris along several miles of riverbed. Few flood controls or warning systems existed in 1976. Some individuals ignored warnings or drove into the canyon and were lost in raging flood waters. One hundred forty-five people did not survive this natural disaster. Of those who did, many have stories of clinging to rocks, climbing trees, or scrambling to higher ground. Flood of ’82 Lawn Lake lies high in the Mummy Range in Rocky Mountain National Park. In the early 1900s, prior to the establishment of the park, a 26-foot high earthen dam was added at the outlet of this lake tripling its capacity. On a sunny Thursday morning, July 15, 1982, a 95-foot long section of the dam failed. Over 300 million gallons of water surged down the Roaring River forming waterwalls up to 30-foot high. In Horseshoe Park, a large open meadow in the national park, trees, sand, and boulders quarried from the riverbed settled, forming an alluvial fan (debris moved by water). This Alluvial Fan now covers 42 acres, contains boulders weighing up to 452 tons, and is 44 feet deep in places. The heaviest rocks and debris carried by the fast moving water were dropped as the water slowed down. Lighter debris such as sand carried farther. Fall River, swollen by the waters from Roaring River, flowed eastward through Horseshoe Park down into the town of Estes Park. When the water reached Cascade Dam near the national park, it topped the dam, causing the dam to collapse. The resulting four to five-foot wall of water gouged out the river channel taking trees, rocks, cars, propane tanks, and other debris with it. The debris formed a dam at the west end of downtown Estes Park, forcing the water to flow down the main street, well out of the normal river channel. The water and its debris flowed into Lake Estes and was contained behind the Olympus Dam. Three people lost their lives in this flood: one who was camped just below the dam and two who went to take pictures of the rushing waters near the Aspenglen Campground just at the boundary of the national park.

Powerful flood waters scour river and stream channels and deposit material downstream, thus changing the land on both large and small scales. Both the Big Thompson Canyon Flood and The Flood of ’82 challenged nature’s and people’s ability to change and adapt. The Big Thompson Canyon flood was declared a national disaster, thus providing financial and other resources to help people do the necessary recovery work. This work began within days of the flood; flood warning systems were improved; areas of the canyon were revegetated; and the roadway, U.S. Rte. 34, was extensively rebuilt. The Flood of ’82 was also declared a national disaster, bringing financial aid for rebuilding homes and commercial establishments. The flood also provided the impetus to begin a major renewal of the commercial district of the town of Estes Park. Both floods destroyed some natural areas and enhanced others. While scars are largely healed, in some areas they are still obvious. Fish and plant life have returned as riverbeds stabilize. Dead trees are being used as bird and insect home sites; new revegation continues to expand into the scoured areas, providing cover and food for wildlife. The two floods motivated Rocky Mountain National Park to acquire title to all reservoirs remaining in the park and to remove their dams, returning high altitude lakes to their natural size. Both floods were tragic in terms of life and property loss. However, both provided opportunities to study and learn about recovery processes in high altitude ecosystems. Within one year following the Flood of ’82, 35 species of willows and grasses were growing in the damaged areas. Birds along the Roaring River and in West Horseshoe Park near the Alluvial Fan have returned and increased in number. Scientists have recorded the changes in distinctive lobes of fine sediment in the rivers affected by the floods. Predictive models have been developed for how water behaves in floods similar to the Big Thompson Flood and the Flood of ’82.

History.denverlibrary.org:

On Tuesday morning, Stephen Gillette set out on his route through Rocky Mountain National Park an hour earlier than usual. Mechanical issues meant that two of the A-1 Trash Co.’s trucks had been unable to make their rounds the preceding day, so he had set off before dawn to put a dent in the backlog. Around 6:15 in the morning, shortly after pulling into the Lawn Lake trailhead lot, he heard a roaring sound which he initially mistook for a jet about to crash. He realized his mistake when he looked for the source of the sound, but instead of seeing a jet he saw “…a ponderosa pine, limbs, bark and all, the whole thing, just sailing up, above the other trees…”.

He quickly backed toward the entrance, pulling his truck across the road to prevent a Michigan tourist from entering the lot. He exited the cab, racing to the emergency phone located at the trailhead entrance. Fortunately, the phone worked that day (it didn’t always), and at 6:26 the Park Service dispatcher heard Gillette, yelling to be heard over the sound of the roar, saying “A lake, a dam – something’s flooding!” After identifying himself, he informed the dispatcher that he’d barricade the road while waiting for the rangers to arrive.

Two park rangers arrived shortly, and within minutes of each other. The three quickly set about locking the Fall River Road gate, and barricading Horseshoe Park Road. By the time those tasks were completed, they were standing in rushing, muddy water up to their knees. It was clear to the Park Service that they were dealing with an emergency, but they didn’t yet know what exactly the emergency was, nor how severe.

As it happened, the source of the problem was the Lawn Lake Dam. The dam was most likely constructed in 1903, and had been expanded in 1931 to increase its capacity. Over the years, the makeshift road which had been built to aid in the dam’s construction had all but eroded away. By 1975, inspectors were forced to hike six miles each way in order to view the earthen dam. In 1975, the inspector recommended a more thorough examination once the snow melted, and in both ’77 and ’78, the dam was categorized as being in “fair” condition, and possibly in need of repair. Due in part to its inaccessible nature, no comprehensive examinations were done, and no repairs were made.

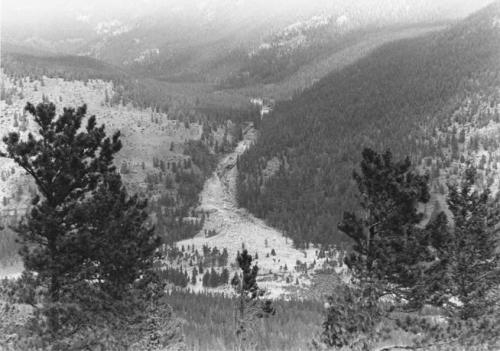

Shortly after 6 a.m. on July 15, 1982, the Lawn Lake Dam underwent a catastrophic failure, and for a brief period the Roaring River let the world know how it got its name. 30 million cubic feet of water tore through the landscape, ripping trees out by their roots, and sweeping tons of boulders and other debris along in its passing. Upon reaching the mouth of the valley at Horseshoe Park, where the torrent was able to spread out and slow for a bit, it left an alluvial fan covering over 40 acres.

That still wasn’t the end of it. Much of the water, mud and detritus rushed across the Horseshoe Park basin, merging with Fall River and backing up behind the Cascade Dam. Fortunately, this dam was able to withstand the added pressure, but the sheer volume meant that the dam was quickly overtopped, causing a secondary flood surge. Fortunately, much of the debris remained behind the dam, as this resultant swell poured through the town of Estes Park.

Floodwaters in the town reached between five and six feet in depth, and left two feet of thick mud in its wake as it hurtled through the town, joining the Big Thompson river on the far side. Elkhorn Avenue, Estes Park’s primary commercial strip, roughly paralleled Fall River, and sustained the bulk of the damage. When all was said and done, the flood did over 31 million dollars in damage to Estes Park alone, most of which wasn’t covered by insurance.

All things considered; it could have been significantly worse. Despite the event’s magnitude and force, only three people lost their lives; a lone hiker who had camped near the banks of the Roaring River (and who likely never knew what hit him), and a couple who returned to their campsite below the Cascade Dam, shortly before it overtopped. Given that the campground had been evacuated by the Park Service, it’s highly likely that the death toll would have been much higher if Stephen Gillette hadn’t set out on his route an hour earlier than usual that day.

I tried and tried to find before and after photos of the flood in order to make a comparison, but I gave up. There don’t seem to be any. : (

Doesn’t look very large in this picture, but you can tell in the previous one.

You can see the Roaring River making its way through the debris.