Raccoon Mountain, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Then God said, “Let the land produce vegetation.” ~ Genesis 1:13

Did you notice anything unusual?

Definitely not something you see every day –

only the father of a daughter would walk around in public like this. : )

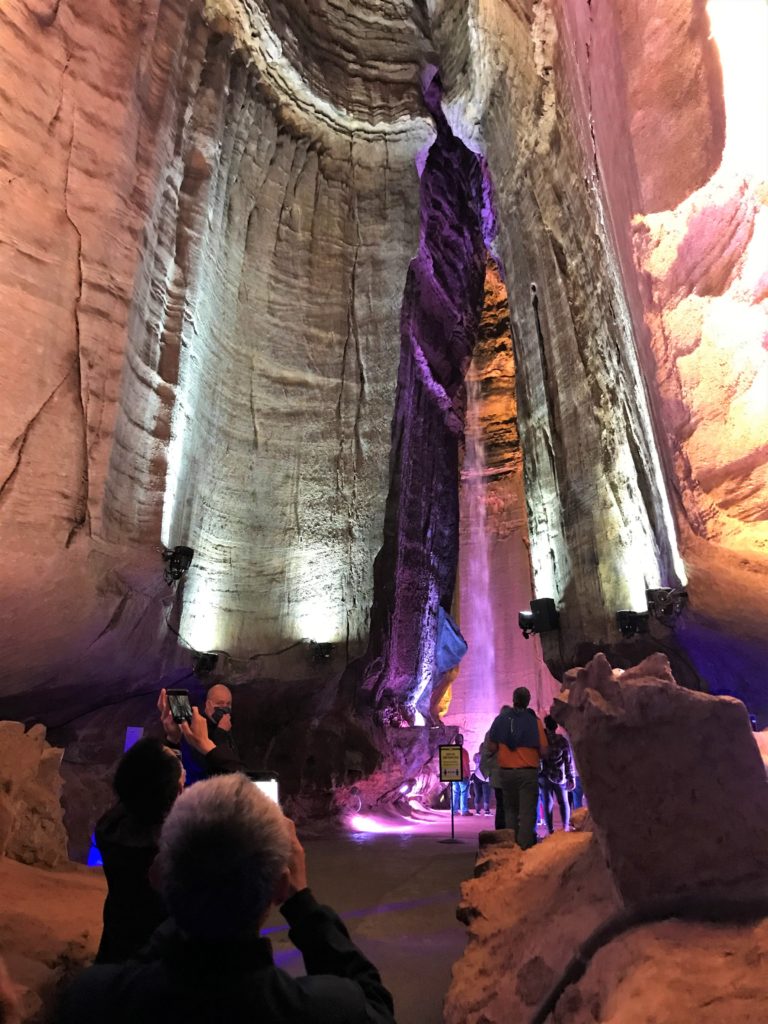

Today brought History Lesson Number Two (or is it two and three?). To begin our day, we took in an indoor, 145’ waterfall! Are you astounded? Are you questioning my integrity? It’s true!

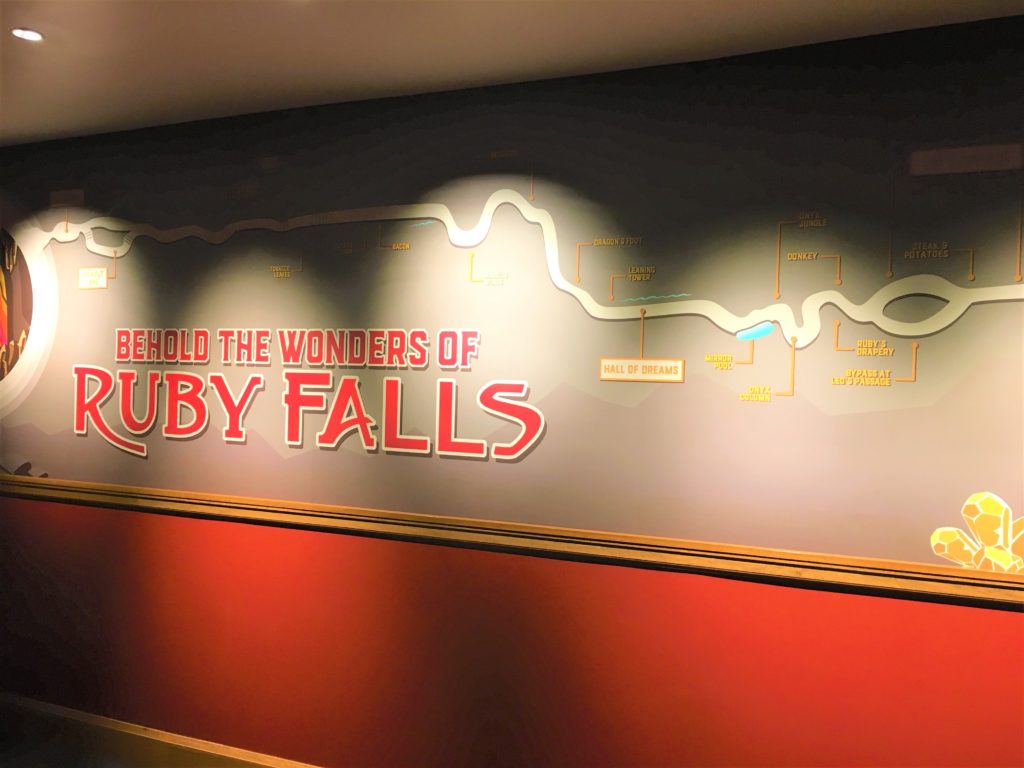

The long-time tourist attraction (90 years and counting!), Ruby Falls, was recommended by my brother, and we’d seen other reviews of it as well. And billboards. Lots of billboards! The novelty of going into a cave and finding a giant waterfall intrigued us. Once we were there, the story of how it began and evolved did too.

Do you find yourself doing that? Smiling broadly when your face is completely covered? : )

Then they took you down in an elevator. Which travels 26 stories (260′) in just 30 seconds.

That means, you go 8 1/2 miles an hour!

Most elevators travel at a speed of 1 1/4 – 2 1/4 miles an hour!

I wonder . . . What will Christmas look like for people this year?

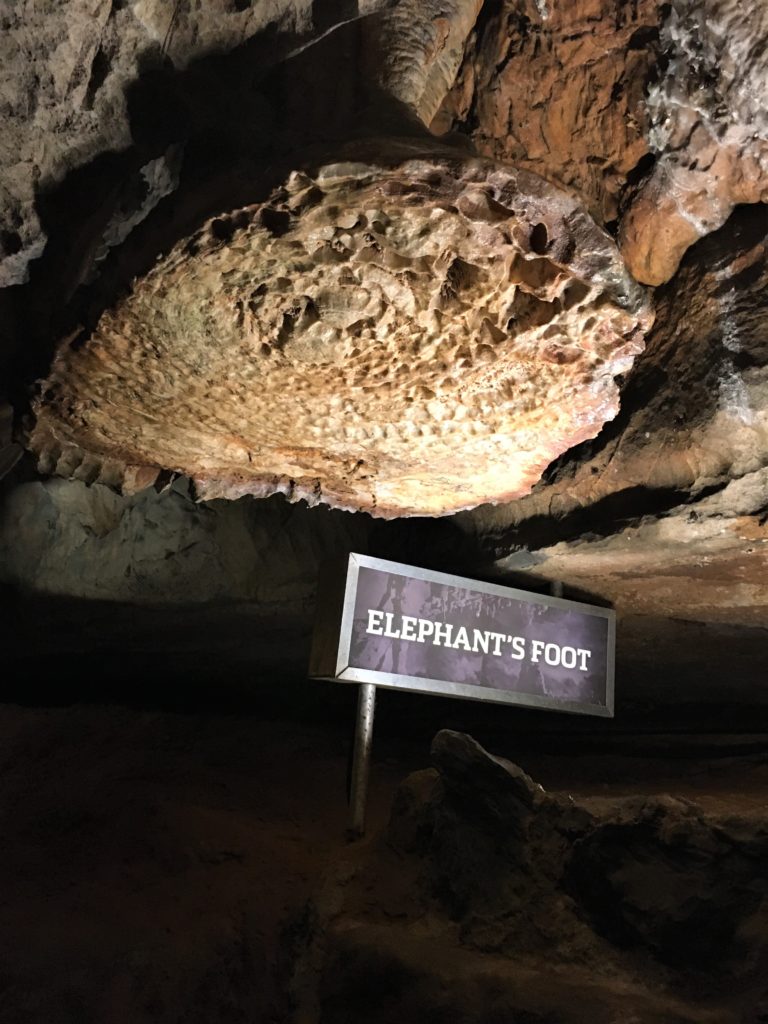

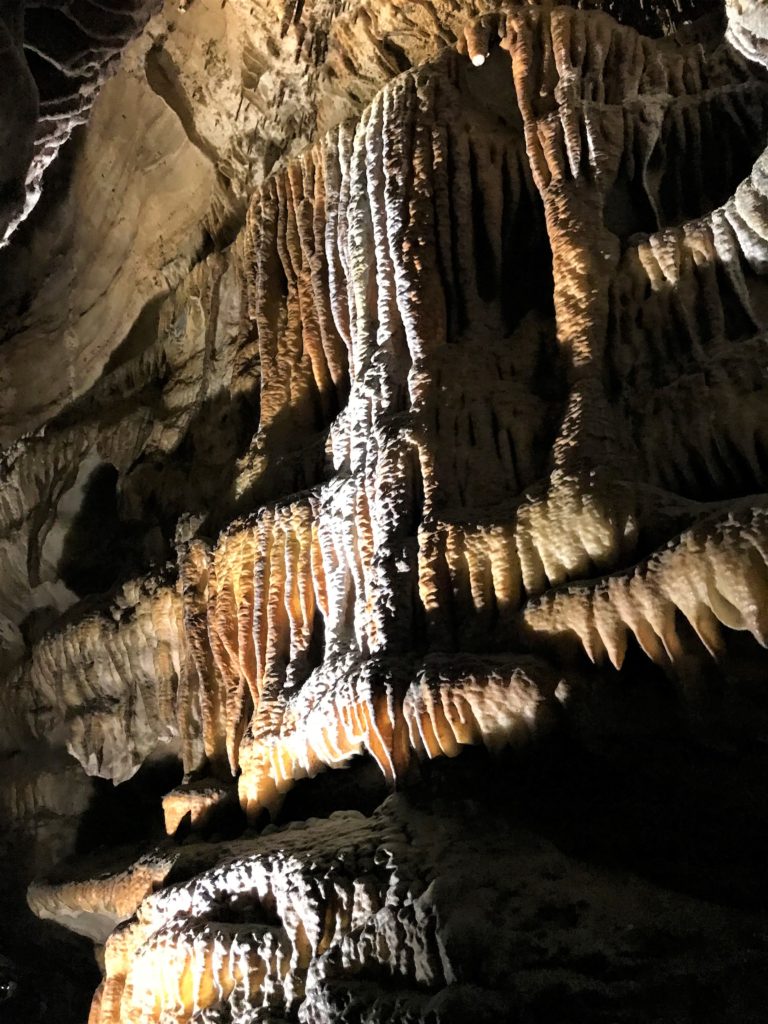

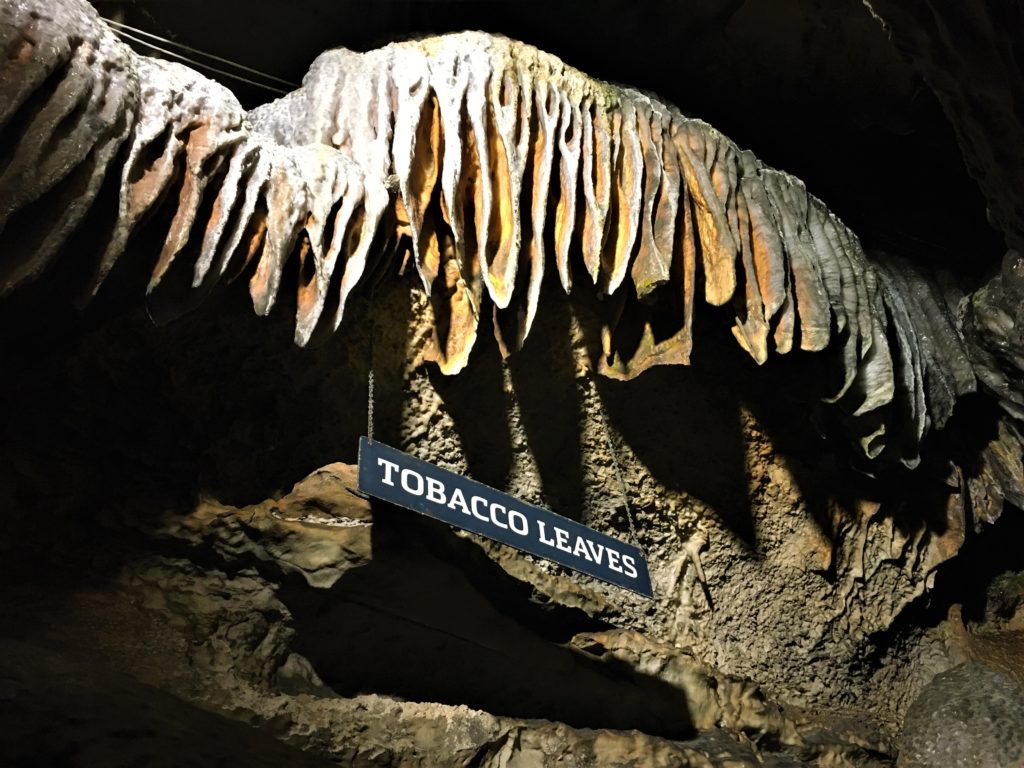

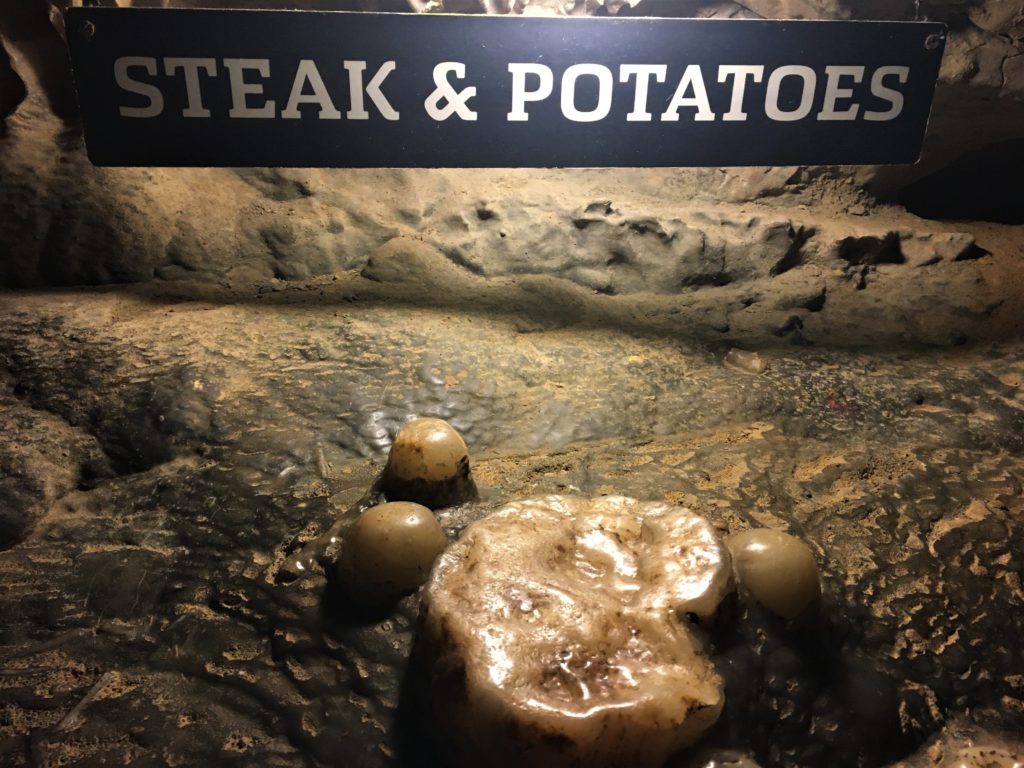

You have to stop and wait for your phone’s camera lens to focus in the dark.

It’s hard to do that though when your in a guided tour line.

Just keep in mind – – everything always looks better in person! : )

In the midst of our tour, we were given the opportunity to watch a short film about the discovery of Ruby Falls. It was an interesting tale, and I’d love to share the video with you, but alas, I cannot. So I’ve done the next best thing! I located information on the web that nearly matches what we heard, and a few other things we didn’t.

I borrowed the bulk of the following information from Meghan O’Dea (cityscope.com) and Dave Tabler (appalachianhistory.net), along with snippets I found on several other sites.

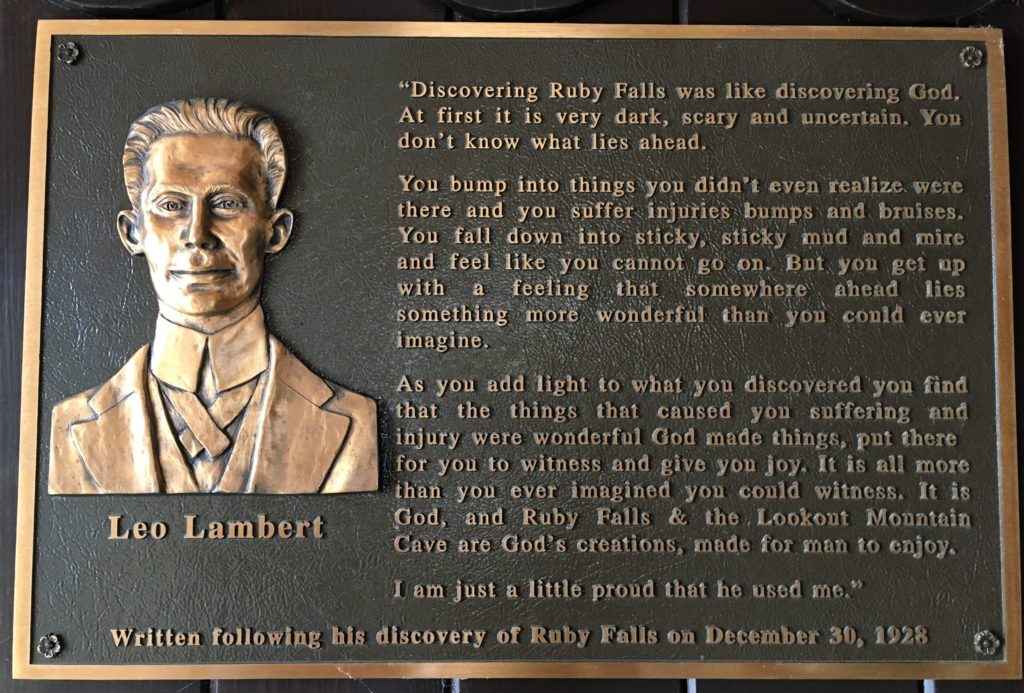

Many a young bride is given a beautiful gemstone as a romantic token, but few went so far as Leo Lambert, who gave his wife Ruby a geological treasure of a different sort– a whole cave and waterfall deep inside Lookout Mountain. “It was truly a love story from the beginning,” says Leo and Ruby’s granddaughter Jeanne Crawford. “He had fallen in love with her when she was 14 and he was 15 and followed her to Chattanooga from Indiana.” They were married in 1916.

A chemist with a penchant for caving, he was the first person to explore the Tennessee Cave on Mount Aetna (now known as Raccoon Mountain Caverns, where we’re staying!), and at one time managed the Nickajack Caverns in Marion County, TN.

Lambert was originally intent on preserving a famous cave that many early Native Americans, Chattanoogans, and even a U.S. President (Andrew Jackson) had explored. However, the famous Ruby Falls cave was found quite by accident.

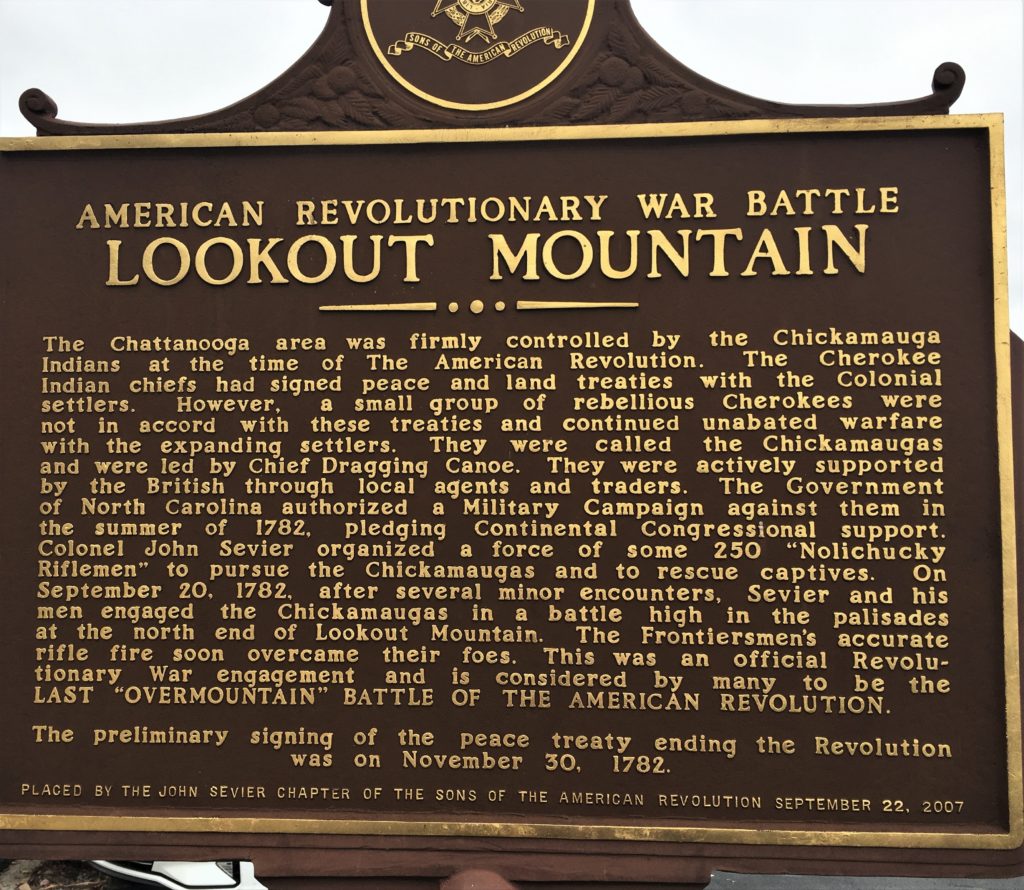

Given his knowledge of Tennessee caves, Lambert surely would have been aware of the cave’s colorful history: used first as a campsite by Native Americans, later a hideout for outlaws. During the Civil War, the caverns were used by both Confederate and Union troops. Many soldiers wrote their names and units on the walls.

It had been 11 years since the Southern Railway had built a railroad tunnel along the face of Lookout Mountain and through some portions of the mountain for one of its lines. The original Lookout Mountain cave had, unfortunately, been sealed off when the Southern Railway laid new tracks as Chattanooga entered its heyday as a railroad town.

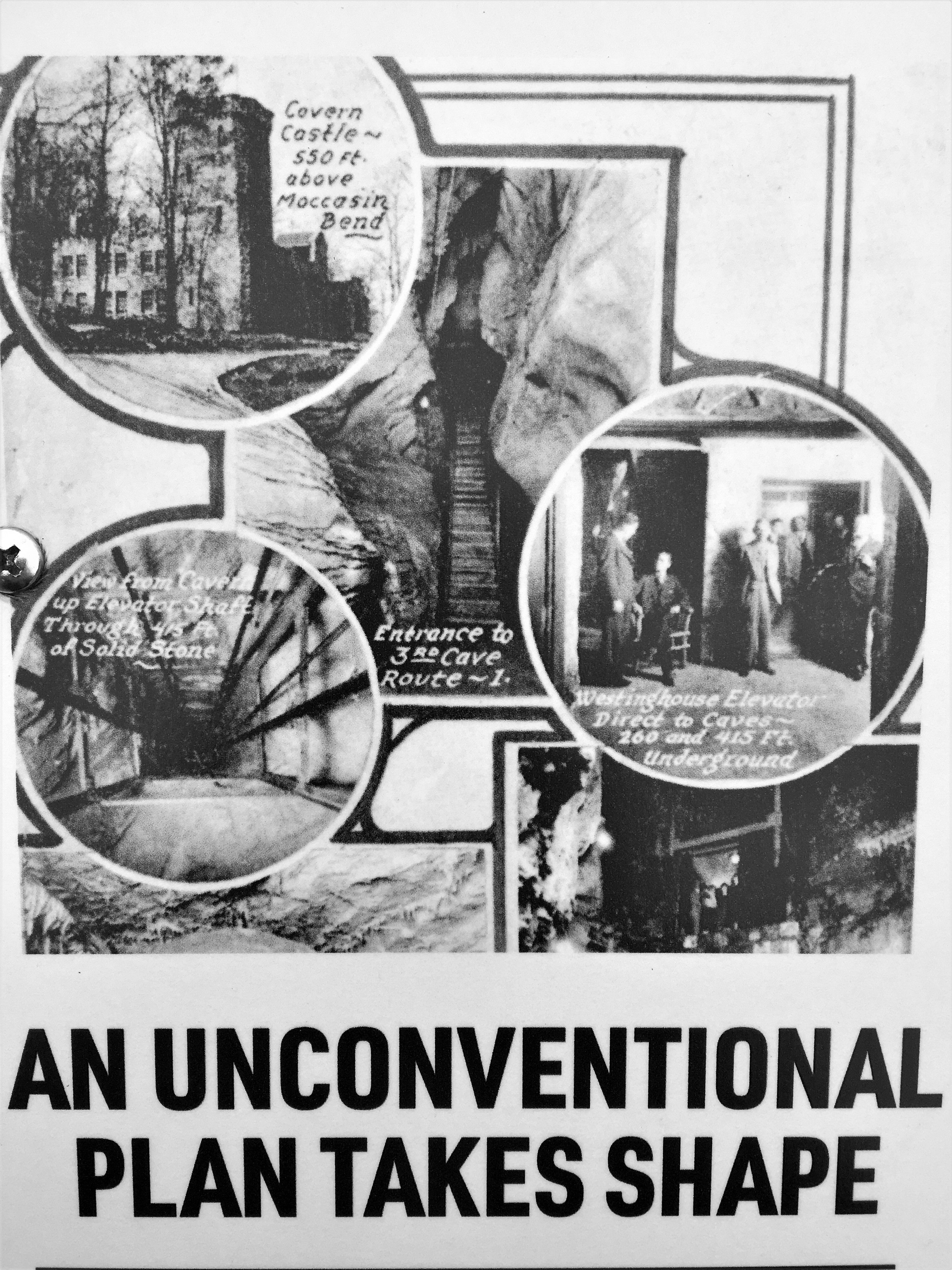

In 1923, Lambert decided to drill open the cave and become a tour operator. He formed Lookout Mountain Cave Company and purchased land above the cave. He planned to make an opening further up the mountain than the original natural opening and transport tourists to the cave via an elevator.

In 1928, to get around the blockage, Leo Lambert, along with a mining company from Birmingham, Ala., selected a site for an elevator shaft into the original cave and began drilling. Midway into drilling the 400-foot elevator shaft, on December 28, a worker operating a jackhammer discovered a void in the rock and felt a gush of air. A small crevice was opened, about 18 inches high and five feet wide.

Quite by accident, they discovered a second cave that proved even more beautiful and popular than the first. “It took an entire day to drive through five feet of solid limestone and they found the only crack in the whole thing,” says Crawford. “If they had drilled either way, they would have missed it.”

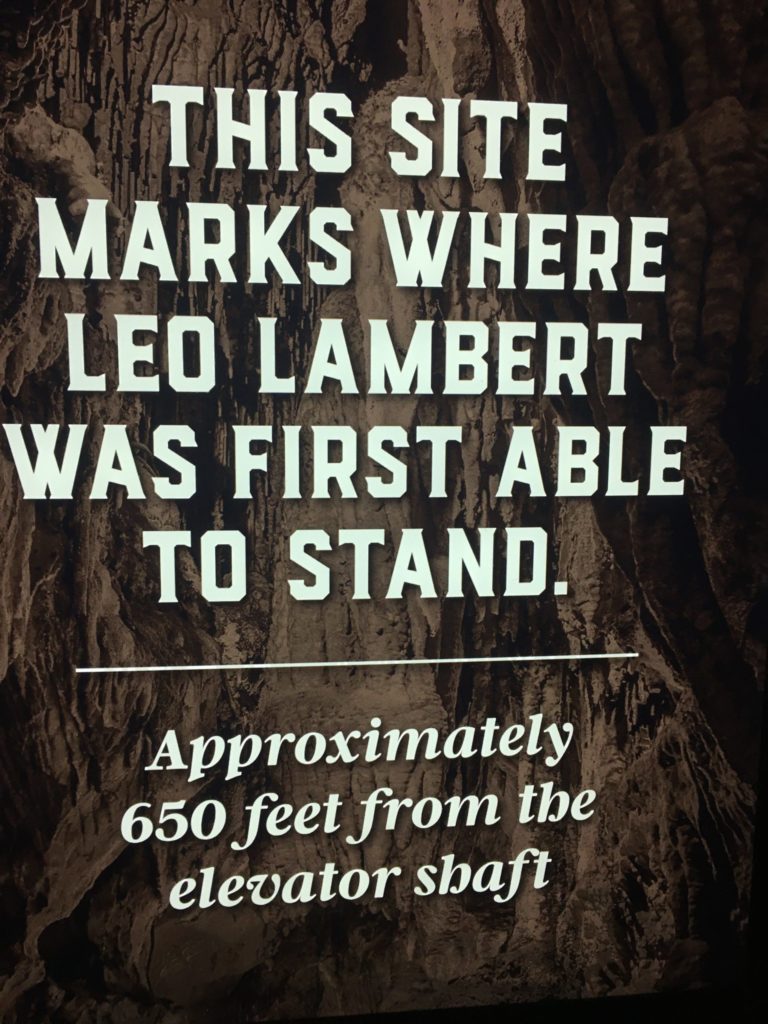

Lambert and other corporate officials immediately decided to investigate it and spent 17 hours on this first exploration trip, crawling through a space that was 18” high and 5’ wide.

Especially in a place that’s never been explored before!

It took them 3 hours of crawling before they could stand and an additional 7 hours before they discovered the waterfall.

It took them just 7 hours to return (She said sarcastically. Can you just imagine being the ones left behind while they were gone? They had no idea what had happened to them! How long do you wait before you send in a search party?). At any rate, after 10 hours, they discovered the passage opened into a falls cave. They came back with a description of a cave with beautiful formations and an amazing 145-foot waterfall, located 260 ft (86 yards) inside Lookout Mountain, and 1,120’ below the surface. The fall is fed by rain water and natural springs and flows into a landing pool which drains into the Tennessee River. On his second trip Lambert was accompanied by his wife Ruby. On this trip he named the waterfall – after her – Ruby Falls.

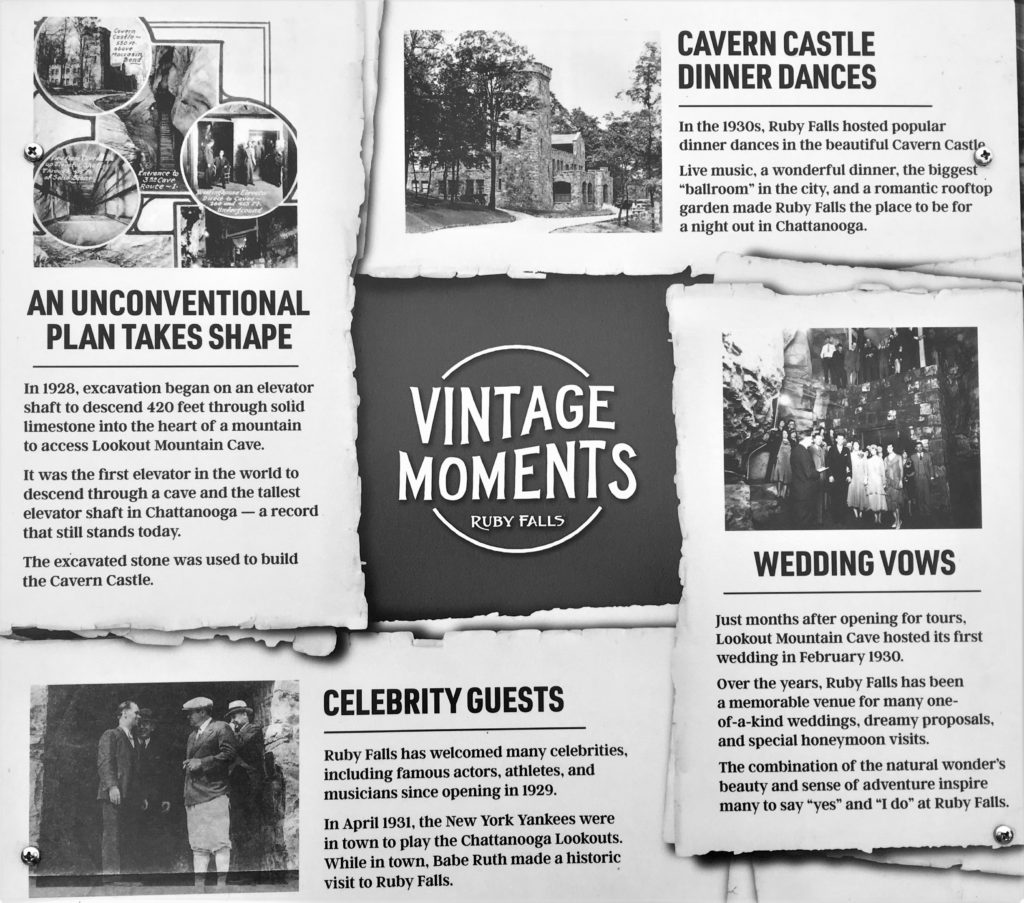

Lambert decided to develop both caves and to offer two cave tours. After 92 days of work, day and night, the elevator shaft reached the original cave. The elevator was installed, paths were prepared, and the original cave opened to the public in 1929. The entrance building, Cavern Castle, looks like a 15th century Irish castle. It was constructed from limestone excavated from the elevator shaft. Development continued in the new cave and in 1930 the second tour to Ruby Falls was opened to the public.

At first the two caverns were shown on separate tours, but the popularity of the falls far exceeded that of the lower cave and that trip was discontinued in 1935. I learned from another source, an additional reason it was unpopular and closed – the place was full of soot! In 1961, a scientific expedition was allowed into the original Lookout Mountain Cave, where they found and mapped a previously undiscovered passage. They also found that nearly every up-facing surface was covered in soot that had found its way in through micro cracks. The soot was from the trains that traveled through the mountain. The expedition members exited the cave covered in soot. The ecosystem and formation of the cave is irreparably damaged, due to the low oxygen levels and lack of air flow in the cave.

In 2005, the Tennessee Elevator Inspectors ordered that the lower elevator shaft into Lookout Mountain Cave be permanently closed.

After years of financial struggle during the Great Depression, the Lookout Mountain Cave Company declared bankruptcy. New ownership launched an aggressive advertising campaign, based on roadside signs, and made Ruby Falls into what is today; one of Chattanooga’s major tourist attractions.

Motorists travelling on I-75 in the 1970s and 1980s were subjected to dozens – maybe hundreds – of billboards along their route with the words “SEE RUBY FALLS” beginning hundreds of miles north and south of the falls itself. Ruby Falls remains a staple of Chattanooga tourism, operating daily. Ruby Falls is owned by the Steiner family of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Ruby Falls and the larger Lookout Mountain Caverns complex have been designated a National Historic Landmark. It is often associated with the nearby Rock City attraction, which lies atop Lookout Mountain.

Johnny Cash and Roy Orbison co-wrote a song with the title “See Ruby Fall” in the mid to late 1960s, a reference to the barn roof advertising slogan “See Ruby Falls” ubiquitous throughout the southern United States in the mid 20th Century.

Ruby Falls is the largest underground waterfall open to the public in the United States. It and the larger Lookout Mountain Caverns complex have been designated a National Historic Landmark.

I read on-line that they are currently working on a $20-million expansion project that’s running through 2020. I’m certain it was delayed due to Covid.

The cactus is the tall one, the candle is the one that leaning towards the path.

The candle has an indentation and a small black something or other sticking up like a burned wick.

We should’ve taken a picture of the top too. I’m sure you can imagine it though. : )

If you look towards the top of the picture, you can see his short gray ears sticking up. Great!

This purple light illuminates the stream running beside us.

The highlight of our tour!

while trying to find out why Leo died at such a young age (never did).

They now pump water into the waterfall whenever needed – during the slow water season,

which of course is summer when most of the tourists are here.

Who wants to pay all that money to see a dripping waterfall?

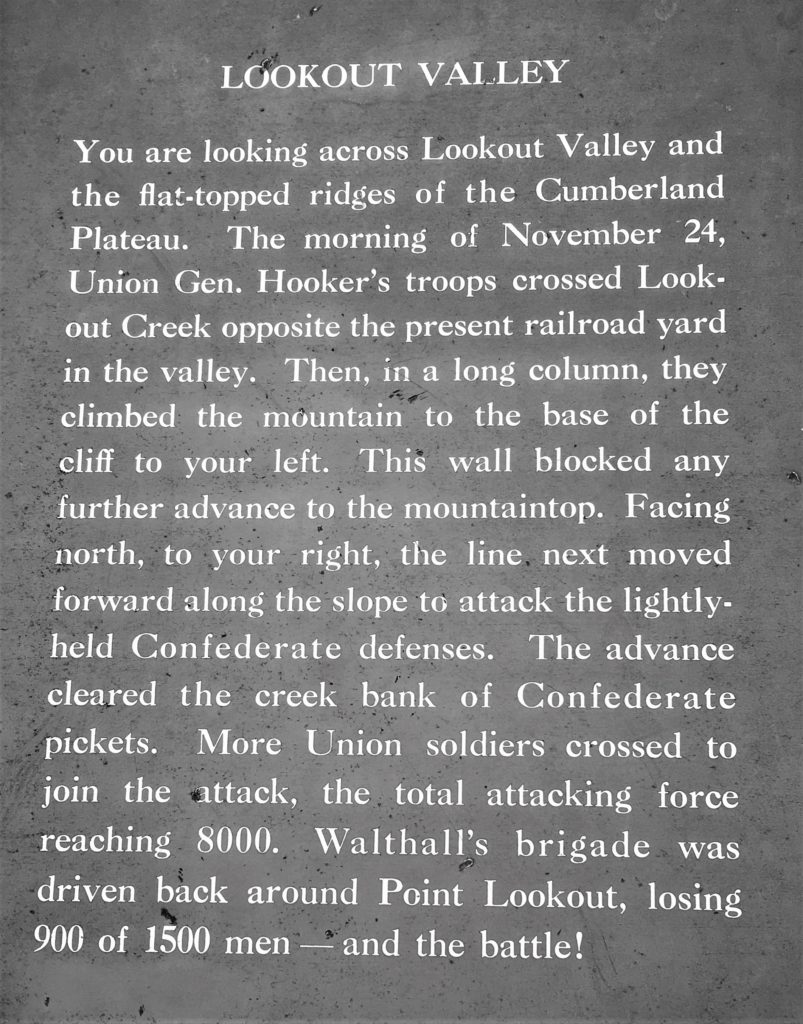

Not a very pretty day, but there were some interesting things to read – –

like this sign – – and some great views.

Guess we’re not color blind!

I’ll bet this place is really something in the Spring!

August 16, 1895 – February 21, 1950

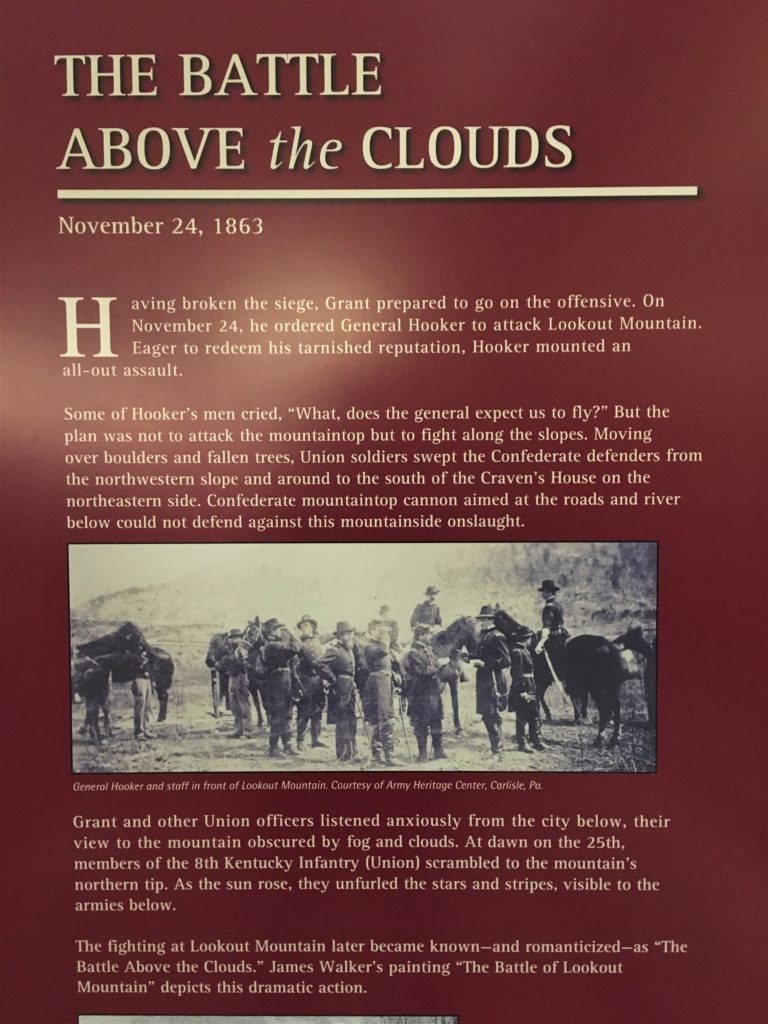

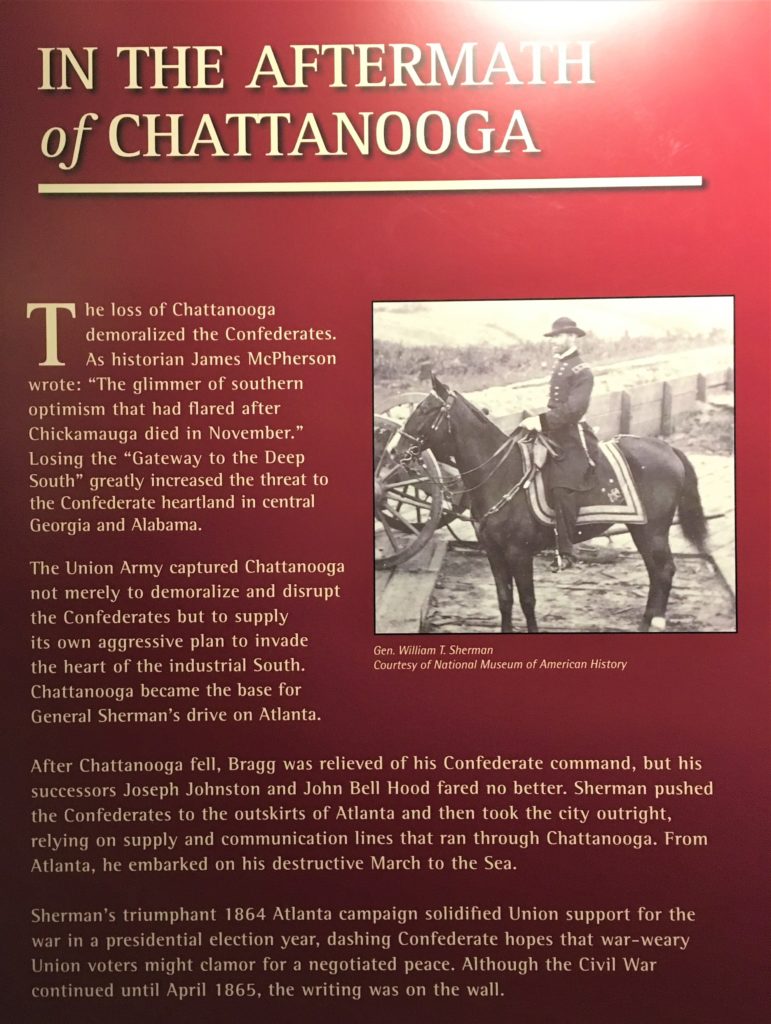

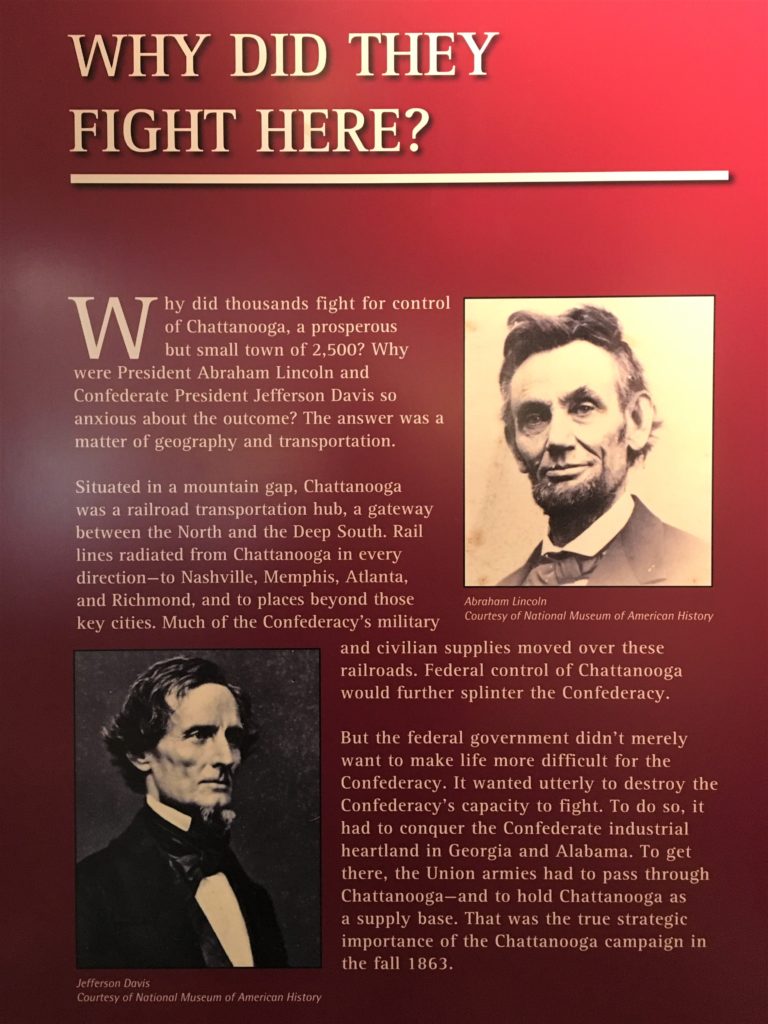

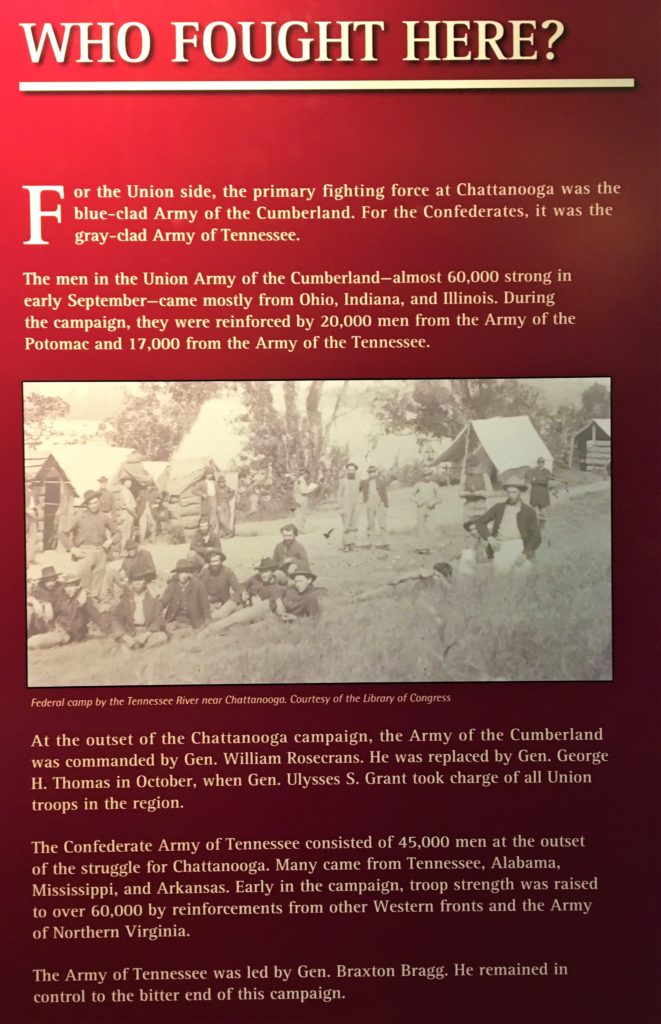

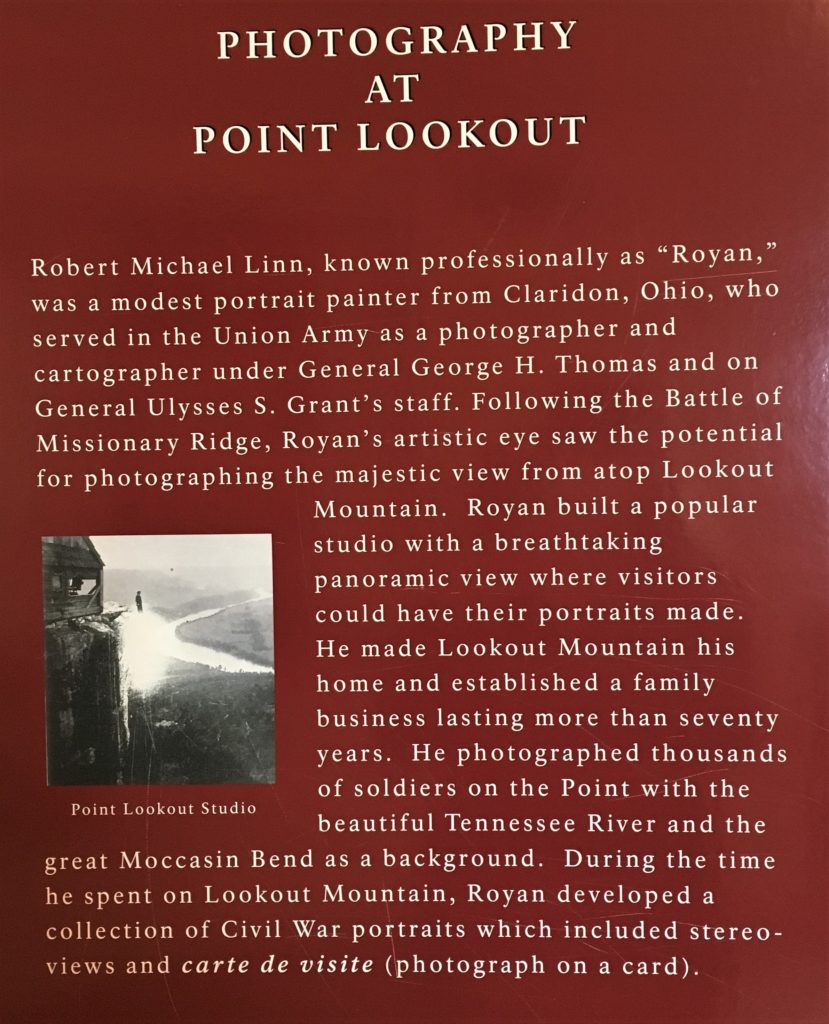

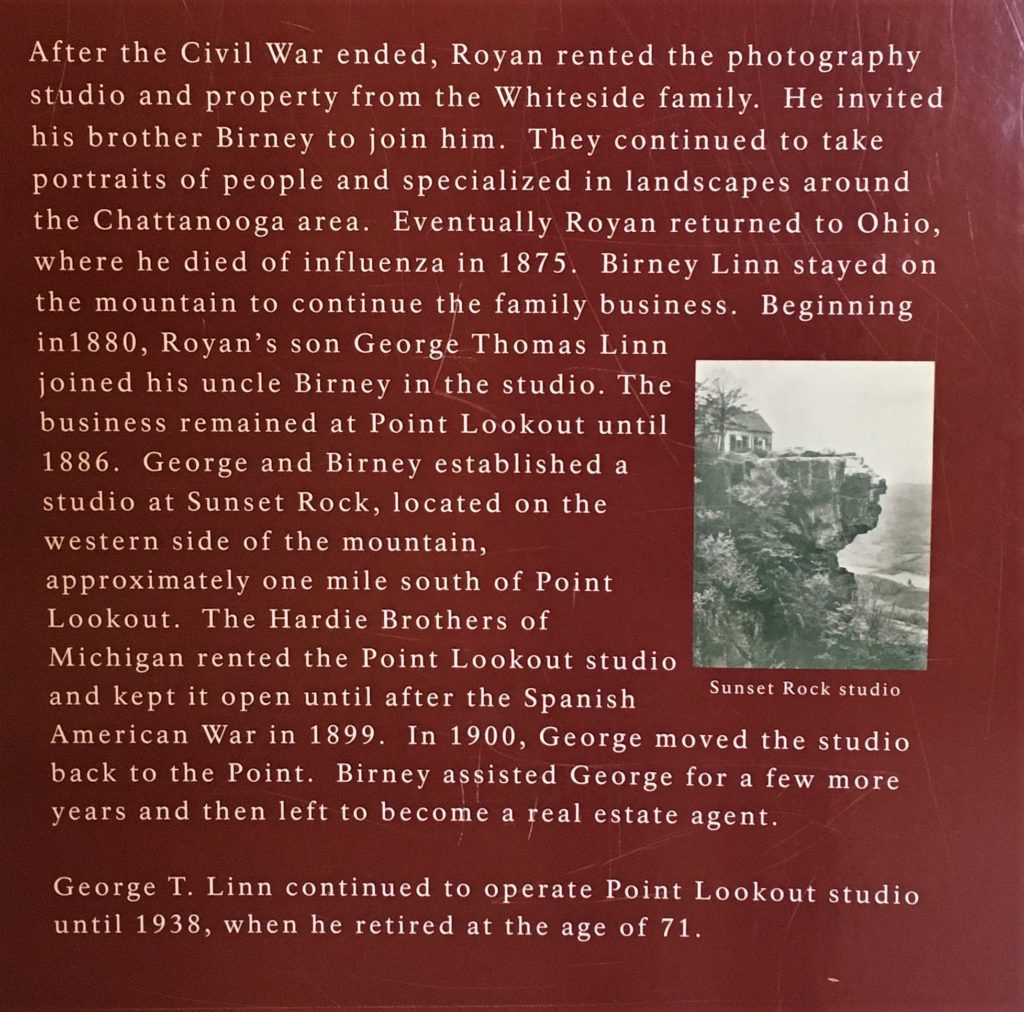

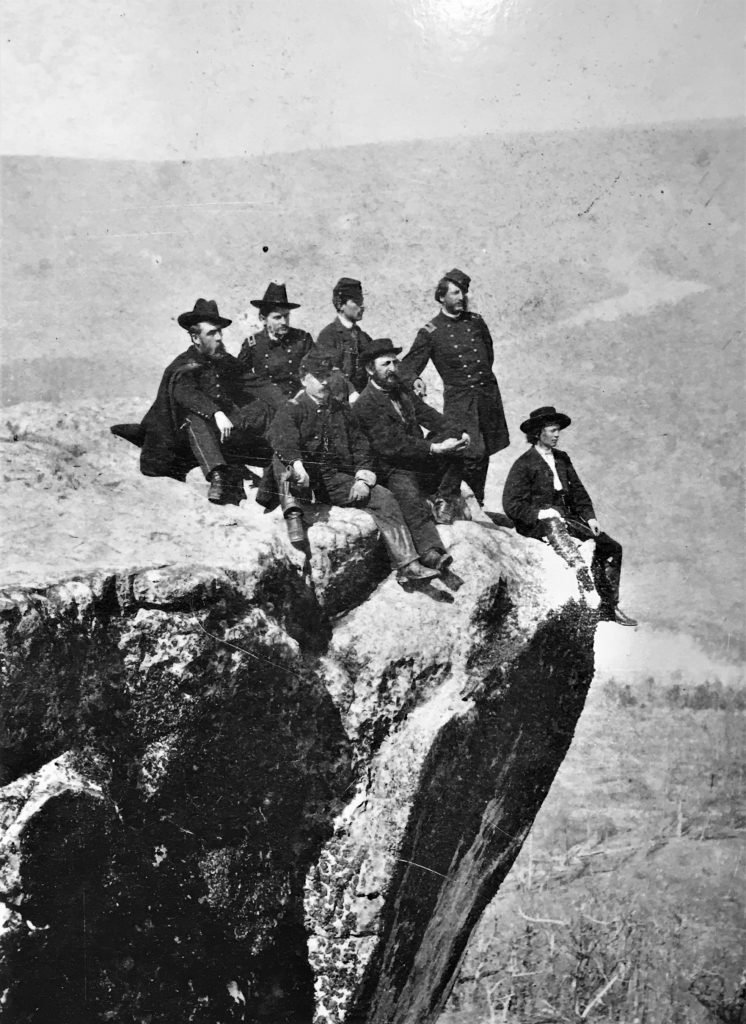

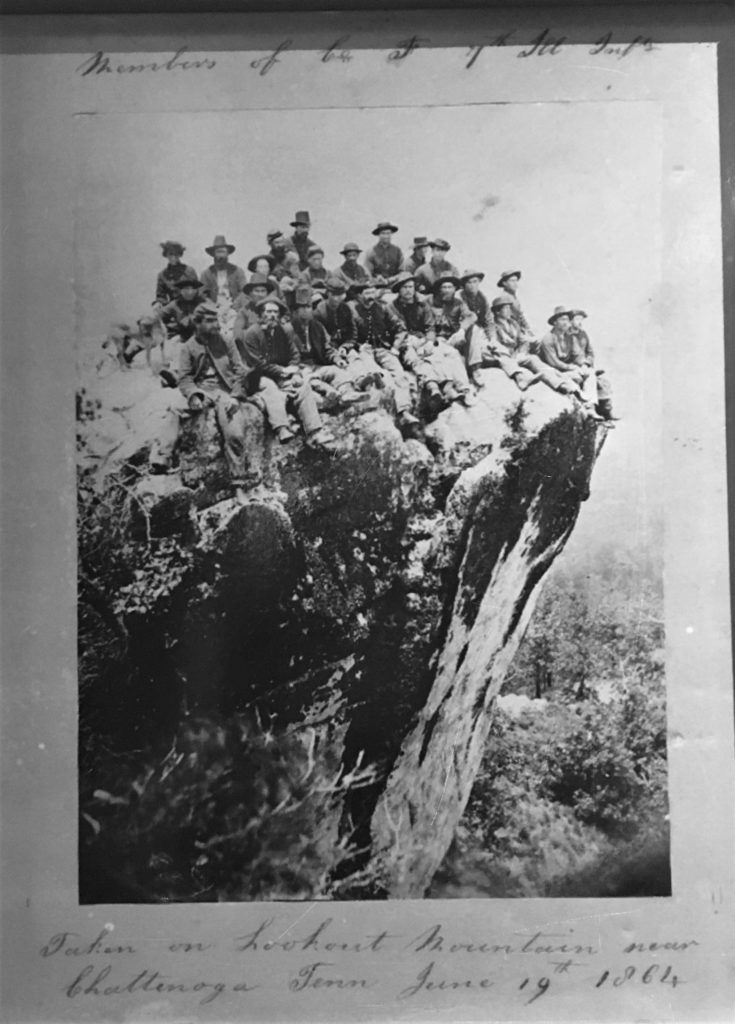

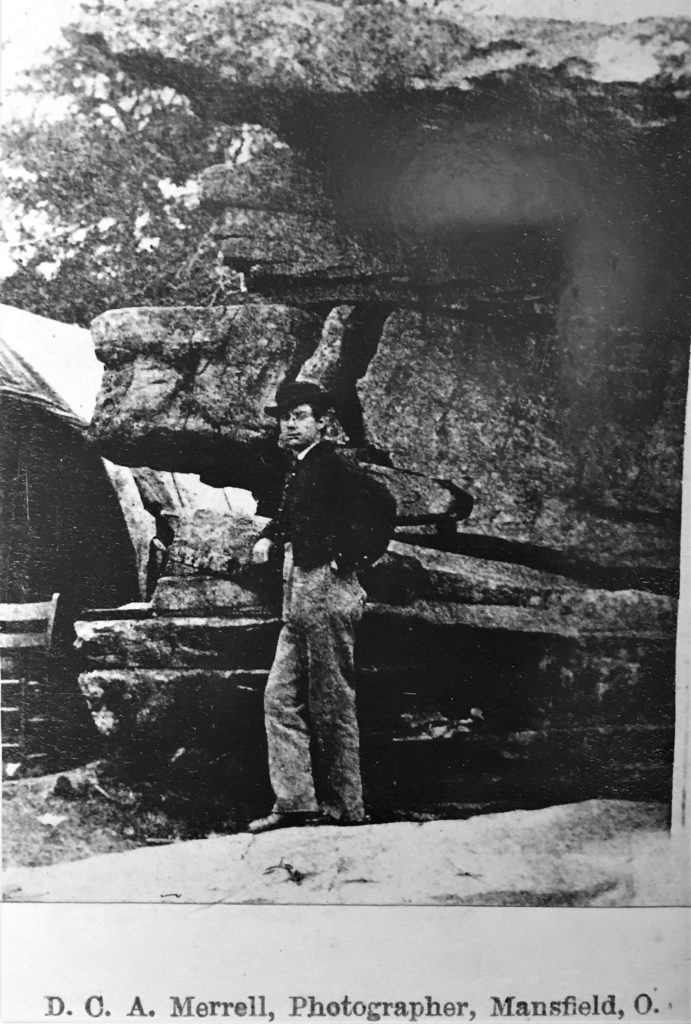

After the waterfall tour, we drove up to Point Park, on top of Lookout Mountain, another section of the area’s National Park, where we learned even more about the Civil War conflict that took place here.

Most of them were difficult to see because they had all manner of foliage protecting their privacy.

Not only did we visit inside the Visitor Center, but we were able to walk around the top of Lookout Mountain, and then check out the Ochs Museum, which was built in the 1950s and housed some additional pictures and information.

I wish I had time to do the research . . . maybe in the future . . .

The following information was on a card near the mural at the Visitor Center:

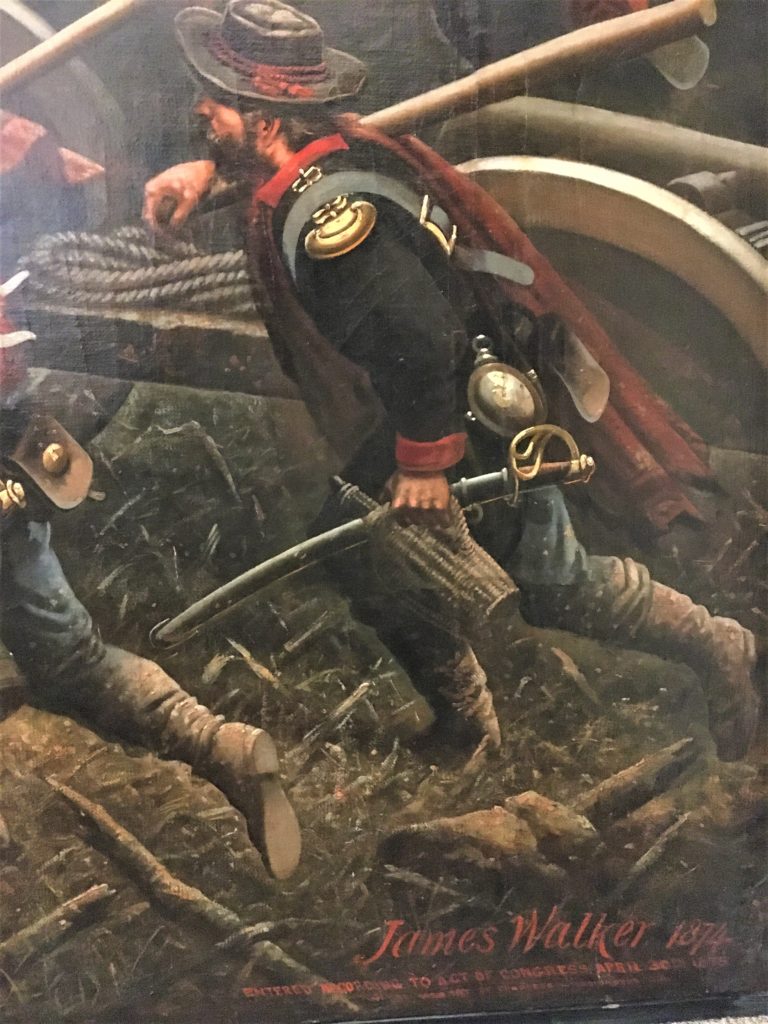

At the mountain’s base, Walker, a well known painter of battle scenes, witnessed the engagement as it swirled above him. In the months following, he interviewed other battle eyewitnesses and produced detailed battlefield sketches and paintings as he began creating a visual record of the fight for Chattanooga. One work, depicting the Battle of Lookout Mountain, caught the eye of General Joseph Hooker, the Union commander during the battle. Seeking to perpetuate his own legacy at Lookout Mountain, Hooker commissioned Walker to produce a 13-by-30 foot oil painting with the general prominently featured in the foreground. Walker spent four years painting this masterpiece, finishing in 1874, for which Hooker paid $20,000. (That’s the equivalent of over $450,000 today!)

For Walker, the painting was the largest he ever completed. For Hooker, the painting placed him in the context of one of the several battles that arguably turned the tide of the Civil War.

After its completion, the painting began touring the country, visiting cities such as San Francisco, New York, and Philadelphia, all the while continuing the legacies of these two men. By 1898, Hooker’s niece moved the painting to Watertown, New York. It was installed and displayed in Washington Hall’s auditorium until the building’s demolition in 1913. Then, the painting was rolled up and moved to storage for the next 44 years, with only a brief exhibition in 1927.

In 1957, the painting was unrolled, examined, and donated to the National Park Service. After accepting the painting, the NPS discovered that between its size and its condition, significant funding was needed to provide it a proper home. It was not until 1985 when the NPS found a partner in Mr. Scott Probasco, a local Chattanoogan, who offered to help fund raise for the painting’s restoration. After raising over $100,000 for conservation, shipping, and final installation, Probasco helped ensure the painting’s legacy, as well as his own. Finally, in 1986, The Battle of Lookout Mountain was installed in the unfinished auditorium of the Lookout Mountain Battlefield Visitor Center, where its legacy continues.

After looking at it up close, we could see why it would take 4 years to complete!

It shows Union and Confederate soldiers shaking hands under the US flag.

The Monument was erected in 1907.

You can’t get to that rock now, but it’s the setting for many historical pictures!

Stunning!

Hard to believe it’s still standing just as it was!

it would probably look pretty terrific.

It took us a minute, but we got it!

Can you?

but we couldn’t figure out where this one was located.

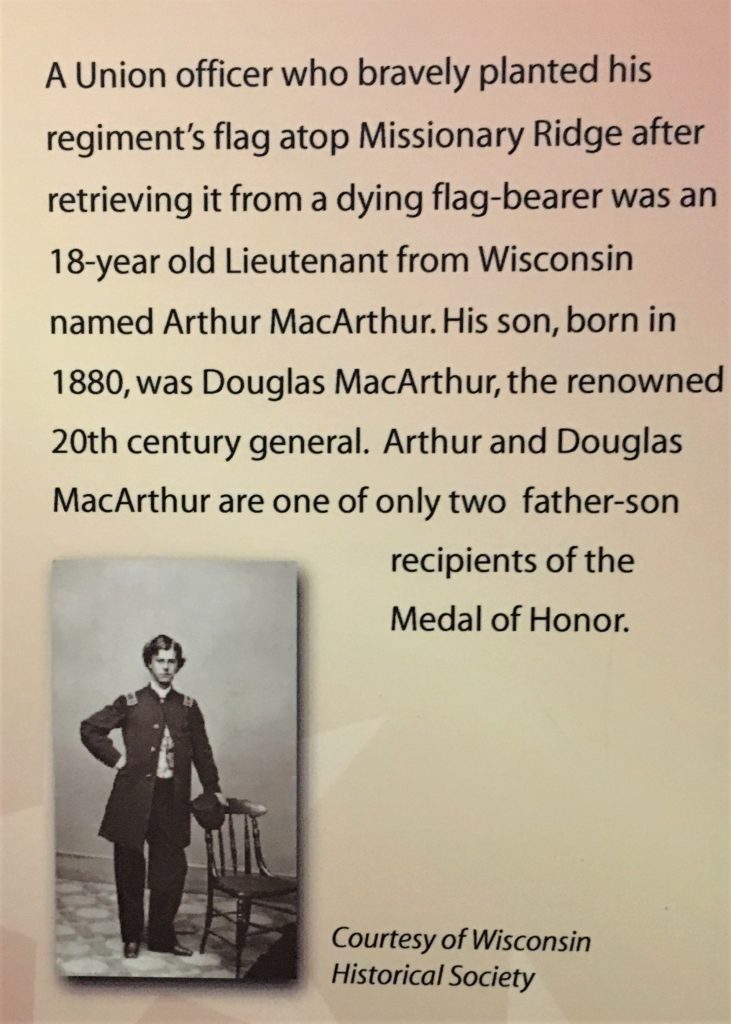

and he reminded us that these men were wearing

smooth-soled leather boots with absolutely no grip!

Yikes!

That’s near our hometown!

In fact, it is the hometown of our daughter-in-law, Shena!

Thus ends History Lesson Number Two and Three.