In my hunt for information on Buffalo Bill, as he came to be known, I used the following sources: Codyyellowstone.org; Britannica.com; Centerofthewest.org; Smithsoniamag.com; cowboyaccountant.com; mentalfloss.com; and a small amount from Wikipedia.

What a fascinating man! I hope you enjoy learning about him, as much as I did. Be forewarned though, this is a very lengthy post, so grab a comfortable seat and plenty of time before you begin. 😊

And keep in mind that there was tons of other information available. Yikes! I had to force myself to stop.

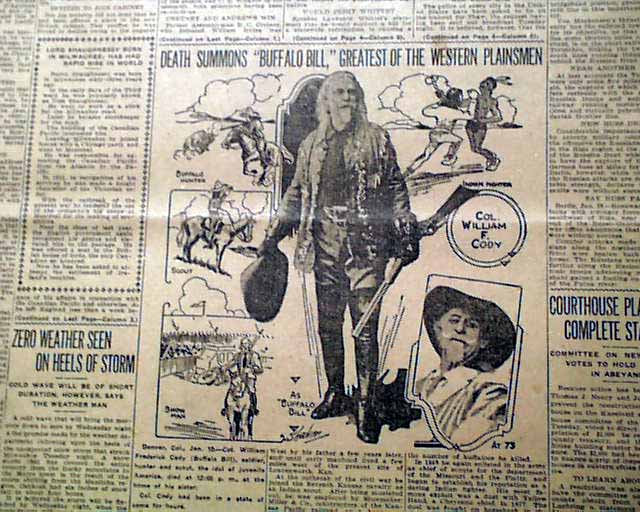

William Frederick Cody aka Buffalo Bill aka Buffalo Bill Cody

Born: February 26, 1846, Scott County, IA, near the town of LeClaire

Died: January 10, 1917, Denver, CO

Buried: June 3, 1917, Lookout Mountain, CO

Spouse: Louisa Frederici (m. 1866–1917)

Children: Kit Carson Cody, Irma Louisa Cody Garlow, Arta Cody, Orra Maude Cody, Ranger Bill Miller

(Yes. His son was named after the famous frontiersman, Kit Carson, whom Bill had met once.)

Isaac Cody, Bill’s father, was a surveyor and real estate investor, born in Ontario, Canada in 1811, but spent his childhood in Ohio. He moved around the Midwest his whole life, from Iowa Territory, where William was born in 1846, then moved to Kansas during a time when the new territory was at its most tumultuous. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act stated that all U.S. territories possessed self-government in all issues, including slavery, turning Kansas into a literal battleground between free state forces and pro-slavery. The town of Leavenworth, where the Cody family lived, was pro-slavery and the groups regularly held meetings at Rively’s trading post. On September 18, 1854, Isaac attended one such gathering and was asked to voice his opinion. When he said he didn’t want slavery extended, he was stabbed twice in the chest with a Bowie knife. Complications from the injury ultimately led to his death three years later in 1857. Bill was eleven years old.

To help support his family, William had already begun working at age nine for the Russell, Majors and Waddell freight company, where he made use of his skills as a horseman. In 1857, at age 11, he took a job as a wagon train “boy extra”. Today, this is the kind of job that would be done by text message — literally. Cody would ride along the length of the wagon train on horseback, taking and delivering important messages to different drivers throughout the train, ensuring everybody had the most up-to-date information. That same year, Cody came to be celebrated as the youngest Indian fighter on the Great Plains after he killed a Native American who helped attack the cattle drive on which Cody was working. Remember, in 1857, he was just eleven years old. On the same cattle drive, Cody met the young Wild Bill Hickok, who intervened on his side in a fight Cody was having with an older man.

Cody was 14 years old when he began riding for the Pony Express in the spring of 1860, but, because he had already delivered messages between wagon trains for Russell, Majors and Waddell, he was initially assigned a short 45-mile run. While some of Cody’s exploits as a rider were the creations of publicity agents, there is no doubt about the courage and dedication he showed while in the service of the Pony Express. Of particular note was a dramatic round-trip ride of some 300 miles in Wyoming between Red Butte Station and Pacific Springs Station on which Cody completed not only his own leg, but those of missing relief riders; a sleepless odyssey of nearly 22 continuous hours of riding. On another legendary ride, Cody outran Sioux warriors to Three Crossings Station, Wyoming, only to find the station keeper dead and the horses stolen. He narrowly escaped to the next station, but, after arriving there, he gathered and led a group of men against the Indians, surprising them at their camp and retaking the stolen horses. Cody’s cunning was the center piece of another often-recounted episode in which, called upon to deliver a large sum of money and fearing that he would be robbed, he hid the currency under his saddle blanket and stuffed paper into his Pony Express mochila (saddlebag). When he was indeed held up at gunpoint, he threw the treasureless mochila at the bandits and then made good his escape.

During the American Civil War (1861–65), Cody first served as a Union scout in campaigns against the Kiowa and Comanche and later, in 1863 he enlisted with the Seventh Kansas Cavalry, which saw action in Missouri and Tennessee. After the war, from 1866-1867, he worked for the U.S. Army as a civilian scout and dispatch bearer out of Fort Ellsworth in Kansas.

In some ways, Cody was the original reality television star, long before the medium was invented.

Cody married Louisa Frederici in 1866, but spent long stretches of time away from her and their four children. In 1904 he sued for divorce, claiming Louisa had attempted to poison him, and the suit turned into a huge scandal covered by most major papers, with reporters dredging up Cody’s earlier affairs and bouts of drinking. The judge ultimately dismissed the case, since the accusations of poisoning were baseless, and stating that “incompatibility is not grounds for divorce.” The couple stayed married and managed to reconcile around 1910, seven years before Cody’s death in 1917.

His nickname came from a job with the Kansas Pacific Railroad. Before his long run as impresario of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Cody bounced around a number of jobs. In 1867 he became a hunter for the Kansas Pacific branch of the Union Pacific Railroad. For a year and a half, Cody delivered 12 bison a day to the hungry workers. It’s estimated he killed more than 4,000 in one eight-month period, and he once killed 48 buffalo in 30 minutes. Despite supporting conservation measures like implementing a hunting season, Cody’s over-hunting as well as that of American soldiers, contributed to the near-extinction of buffalo.

Cody acquired a reputation not only for accurate marksmanship but also for total recall of the vast terrain he had traversed, knowledge of Indian ways, courage, and endurance. He was in demand as a scout and guide, mostly for the U.S. Fifth Cavalry, throughout much of the government’s attempt to wipe out Indian resistance to settlement of the land west of the Mississippi River (1868–76).

During this time, the pulp fiction industry produced inexpensive magazines that romanticized the exploits of the heroes and villains who roamed the plains—including Buffalo Bill, who was a central figure of many of these inflated truths. In 1872, dime novel writer Ned Buntline persuaded Cody to portray himself on stage. The “show business bug” hit Cody, and he formed his own “combination” troupe the next year. The group also included James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok and Texas Jack Omohundro, authentic western characters who gave some credence to the melodrama.

In that same year, Bill hunted buffalo with Russian royalty. When a Russian delegation led by Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, took a four-month goodwill tour of the U.S. in 1871-72, the royal visit was big news. As part of the goodwill tour, U.S. Pres. Ulysses S. Grant set up a buffalo hunting trip. It was organized by Gen. Philip Sheridan (best known for his Shenandoah Valley Campaign on behalf of the Union in 1864) who arranged for Cody as well as Lieut. Col. George Armstrong Custer as scouts. The hunt took place in January at Red Willow Creek in Nebraska. The event was widely publicized, with newspapers writing about the Grand Duke’s affection for an “Indian princess,”—a detail that was almost certainly fabricated to spice up the story.

Also in 1872, while serving the Third Cavalry Regiment as a civilian scout, Cody, who frequently took dangerous assignments that others refused, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroic actions on April 26 as scout for a contingent of the Third Cavalry that was pursuing Indians who had stolen army horses near Fort McPherson in Nebraska. The Medal was for “Documented gallantry above and beyond the call of duty as an Army scout”. In 1917, the medal was rescinded — along with 910 others awarded to civilians — when Congress designated the Medal of Honor as the highest military honor it could bestow.

As you might expect, Cody’s living relatives were not happy about this. For years, they voiced their objections and asked Congress to reconsider. These efforts were unsuccessful, until 1989, when a letter from Cody’s grandson (who was 76 at the time) helped convince Congress that Buffalo Bill deserved to have his medal restored. In 1989, over 70 years after being taken away, Cody’s award was officially reinstated, and his family could once again proudly call him a Medal of Honor recipient.

During the height of the Plains Indians resistance to white settlement, Cody returned to the prairies in summer 1876 to scout for the Fifth Army. On July 17, 1876, just three weeks after Custer and the Seventh Cavalry were defeated at the Battle of Little Big Horn, Cody’s regiment intercepted a band of Cheyenne warriors. When Buffalo Bill, in his stage clothing, killed and scalped a Cheyenne warrior named Yellow Hair (often mistranslated “Yellow Hand”), he reportedly cried out “First scalp for Custer!” Buffalo Bill the frontiersman had proved that Buffalo Bill the character was no mere actor.

Cody published two autobiographies, The Life and Adventures of Buffalo Bill, in 1879, and The Great West That Was: “Buffalo Bill’s” Life Story, in 1916.

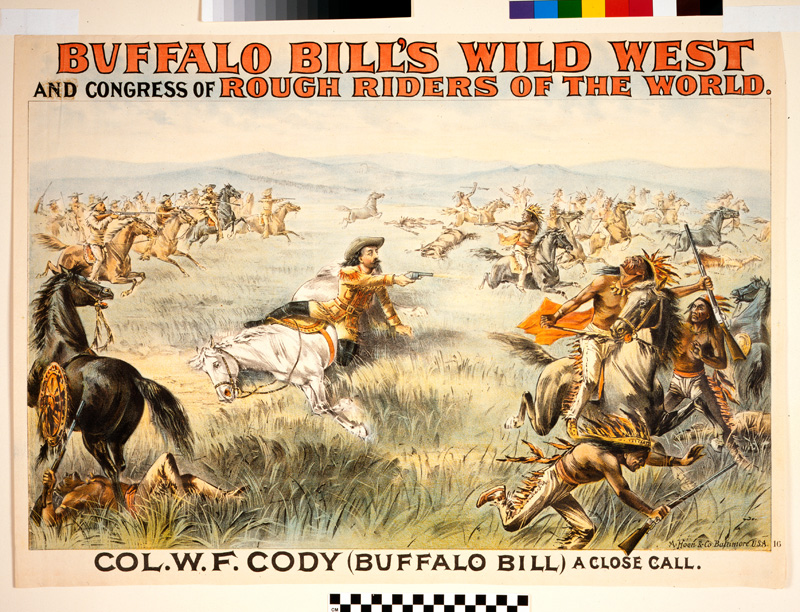

In 1883, in the area of North Platte, Nebraska, Cody founded Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a circus-like attraction that toured annually and propelled him to fortune and worldwide fame. The show began with a parade on horseback, with participants from horse-culture groups that included US and other military persons, cowboys, American Indians, and performers from all over the world in their best attire.Turks, South American Gauchos, Arabs, Mongols and Georgians displayed their distinctive horses and colorful costumes. Visitors would see main events, feats of skill, staged races, and sideshows. Many historical western figures participated in the show. For example, the great Indian chief, Sitting Bull, appeared with a band of 20 of his braves. It also featured sharp-shooting, rope tricks, buffalo hunting and reenactments of historical events like Custer’s Last Stand at Little Big Horn. His show (which lasted 30 years) has continued to influence how we view the West and the country’s past. Annie Oakley and her husband, Frank Butler (both sharpshooters) joined the show in 1885.

Thanks to the work of his manager, Nate Salisbury, Buffalo Bill was invited to perform in London’s American Exhibition in 1887. His voyage across the Atlantic included “83 saloon passengers, 38 steerage passengers, 97 Indians, 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 elk, 5 Texan steers, 4 donkeys, and 2 deer.” Before the show opened, the camp was visited by former prime minister William Gladstone and by the Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII) and his family. Annie Oakley even shook hands with the Prince, and he was so charmed—despite the breach in etiquette—that he encouraged his mother, Queen Victoria, to see it. A performance was arranged for May 11th. It was the first time since her husband’s death two decades earlier that Queen Victoria appeared in person at a public performance. She liked it so much, she asked for another performance on the eve of her Jubilee Day festivities, with the kings of Belgium, Greece and Denmark, and the future German Kaiser William II in attendance. The twice-a-day performances at the American Exhibition averaged crowds around 30,000.

The show’s 1892 tour was confined to Great Britain and featured another command performance for Queen Victoria. The tour finished with a six-month run in London before leaving Europe for nearly a decade. Many of his performers were well known in their own right. Calamity Jane joined the troupe as a storyteller in 1893. You could also see the likes of Gabriel Dumont and Lillian Smith (both sharpshooters). The performers re-enacted the riding of the Pony Express, Indian attacks on wagon trains, and stagecoach robberies. The finale was typically a portrayal of an Indian attack on a settler’s cabin, after which Cody would triumphantly and dramatically ride in with an entourage of cowboys to defend a settler and his family. Many cinematic and various forms of literature about the American West were influenced by Bill’s show.

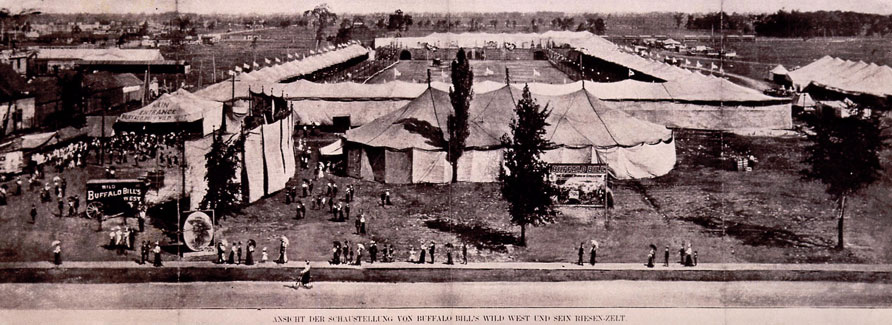

Here the show performs in Germany, ca. 1891. Gift of Thomas Isbell. P.69.1512

With his profits, Cody purchased a 4,000-acre ranch near North Platte, Nebraska. The Scout’s Rest Ranch included an eighteen-room mansion and a large barn for winter storage of the show’s livestock.

Bill Cody was very active in Freemasonry in his later years. In fact, he achieved the rank of Knight Templar in 1889 and 32-degree rank in the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry in 1894. When he passed away in 1917, he received a full masonic funeral — complete with pallbearers dressed in their Knights Templar uniforms.

In 1893, Cody changed the title to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.

For many years Cody performed during the winter and continued scouting for the army in the summer or escorting hunting parties to the West. In the process, the line began to blur even further between the scout William F. Cody and the legend and entertainer Buffalo Bill. Indeed, as early as his scalping of Yellow Hair in 1876, Cody had consciously worn his flamboyant theatrical clothes into battle, later donning the same outfit to re-create his attack onstage.

Although he fought at least 16 Indian battles, he always spoke of his opponents with great respect. He also advocated for the rights of American Indians. As a frontier scout, Cody respected Native Americans and supported their civil rights. He employed many Native Americans, as he thought his show offered them good pay with a chance to improve their lives. He described them as “the former foe, present friend, the American” and once said that “every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.”

In his shows, the Indians were usually depicted attacking stagecoaches and wagon trains and were driven off by cowboys and soldiers. Many family members traveled with the men, and Cody encouraged the wives and children of his Native American performers to set up camp—as they would in their homelands—as part of the show. He wanted the paying public to see the human side of the “fierce warriors” and see that they had families like any others and had their own distinct cultures.

“If you grew up playing cowboys and Indians, you did so because Buffalo Bill’s Wild West made that such a popular part of our memory of the American West,” Johnston (an historian) says. Cody’s show was populated with Lakota and other Plains Indians tribes, and they were portrayed as aggressors who attacked wagon trains and settlers’ cabins—which didn’t accurately reflect the complex reality.

In 1895, Cody was instrumental in the founding of the town of Cody, the seat of Park County, in northwestern Wyoming. Today the Old Trail Town museum at the center of the community commemorates the traditions of Western life. Cody first passed through the region in the 1870s. He was so impressed by the development possibilities from irrigation, rich soil, grand scenery, hunting, and proximity to Yellowstone Park that he returned in the mid-1890s to start a town, which was later incorporated in 1901.

Cody also established the TE Ranch in 1895 (I don’t know what the “TE” stands for – I looked), located on the south fork of the Shoshone River about thirty-five miles from Cody. When he acquired the TE property, he stocked it with cattle sent from Nebraska and South Dakota, and the new herd carried the TE brand. The late 1890s were relatively prosperous years for the Wild West show, and he bought more land to add to the ranch. He eventually held around 8,000 acres of private land for grazing operations and ran about 1,000 head of cattle. He operated a dude ranch, pack-horse camping trips, and big-game hunting business at and from the TE Ranch. In his spacious ranch house, he entertained notable guests from Europe and America.

Despite his characterization as a figure from the past, Buffalo Bill always looked to the future. As a businessman, he invested in projects that he hoped might bring economic growth to the West. With his earnings, he invested in an Arizona mine (which failed miserably and cost him a good deal of his accumulated fortune), hotels in Sheridan and Cody, Wyoming, stock breeding, ranching, coal and oil development, film making, town building, tourism, and publishing. In 1899, he established his own newspaper, the Cody Enterprise, which is still the main source of news for the town of Cody today.

By the end of the 19th century, Buffalo Bill was one of the most-recognized persons in the world. This level of notoriety even earned him an audience with Pope Leo XIII while the Wild West Show was touring Europe.

After years spent in the presence of women like Annie Oakley and Calamity Jane, it’s perhaps no surprise that Cody supported women’s rights. But given how polarizing the fight for suffrage (the right to vote) could be, Cody’s vocal support still seems revolutionary. In an interview with The Milwaukee Journal from April 16, 1898, a reporter asked Cody if he supported women’s suffrage. “I do,” the famous showman responded. “Set that down in great big black type that Buffalo Bill favors woman suffrage… These fellows who prate about the women taking their places make me laugh… If a woman can do the same work that a man can do and do it just as well, she should have the same pay.” (Interesting side note – – while Cody supported women’s right to vote, Annie Oakley did not)

When the reporter followed up with a question about whether women should have all the same liberties and privileges of men, Cody was unequivocal in his response. “Most assuredly I do…. If they want to meet and discuss financial questions, politics, or any other subjects let ‘em do it and don’t laugh at ‘em for doing it. They discuss things just as sensibly as the men do, I’m sure and I reckon know just as much about the topics of the day.” And he practiced what he preached; insisting that all the members of his cast received equal pay.

In November 1902, Cody opened the Irma Hotel, named after his daughter. He envisioned a growing number of tourists coming to Cody on the recently opened Burlington rail line. He expected that they would proceed up Cody Road, along the north fork of the Shoshone River, to visit Yellowstone Park.

In addition to earning money through show business, Cody also invested in land in Wyoming and was involved in the Shoshone Irrigation project.

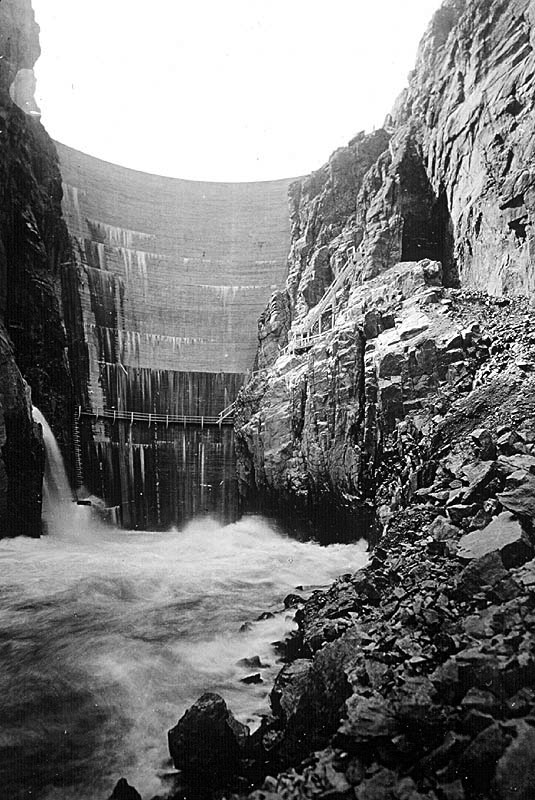

In 1904, Cody transferred his water rights to the Secretary of the Interior and exploratory drilling began for Shoshone Dam that year (later renamed Buffalo Bill Dam). Today the Shoshone Project (system of tunnels, canals, diversion dams and Buffalo Bill Reservoir) irrigates more than 93,000 acres of beans, alfalfa, oats, barley and sugar beets. The dam was one of the first concrete arch dams built in the U.S. in 1910, and also the tallest in the world at 325 feet.

Cody was known as a conservationist who spoke out against hide-hunting and advocated for the establishment of a hunting season. While Cody’s show brought appreciation for Western and American Indian cultures, he saw the American West change dramatically during his life. Bison herds, which had once numbered in the millions, were threatened with extinction. Railroads crossed the plains, barbed wire and other types of fences divided the land for farmers and ranchers, and the once-threatening Indian tribes were confined to reservations. Wyoming’s coal, oil and natural gas were beginning to be exploited toward the end of his life, all of which troubled Cody.

This was in 1910.

Buffalo Bill continued to perform in his Wild West show until 1916, although at age 71 he often had to be helped onto his horse backstage. His last public appearance occurred just two months before his death .While Buffalo Bill’s exhibition remained extremely popular in the United States and abroad, in the end—largely through poor investments, including his purchase of an unproductive gold mine—he lost the fortune he had made in show business. I was unable to discover what his maximum net worth was, but at the time of his death, he was worth “only” $100,000 which is the equivalent of just over $2 million today. In addition, just after his burial in June, 1917, his show was sold for $105,000, which added an additional $2 million plus to the estate.

By the turn of the twentieth century, William F. Cody was arguably the most famous American in the world. No one symbolized the West for Americans and Europeans better than Buffalo Bill. Every American president from Ulysses S. Grant to Woodrow Wilson consulted him on matters affecting the American West. He counted among his friends such artists and writers as Frederic Remington and Mark Twain. He was honored by royalty, praised by military leaders, and feted by business tycoons. Cody was America’s ideal man: a courtly, chivalrous, self-made fellow who could shoot a gun and charm a crowd. Yet as Annie Oakley put it, “He was the simplest of men, as comfortable with cowboys as with kings.”

On January 10, 1917, while visiting his sister in Denver, Buffalo Bill Cody died from kidney failure.

At the time of his death, he had left his burial arrangements to his wife. She said that he had always said he wanted to be buried on Lookout Mountain in the foothills of Colorado, which was corroborated by their daughter Irma, Cody’s sisters, and family friends.

Upon hearing of his death, tributes were made by many world leaders, including King George V of Great Britain, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

On January 15th, his body lay in state in the rotunda of the Colorado State Capitol from about nine a.m. until noon, afterwards he was moved to the Elks Lodge Hall No. 17, in a procession that was led by the governor of Wyoming, John B. Kendrick, a friend of Cody’s. It was there they held a grand state funeral eulogized by Governors and famous friends. After the funeral, his body was placed in a carriage that moved solemnly through the streets of Denver where thousands showed up to say goodbye.

Because he passed away in the middle of the winter, the road to Lookout Mountain, the spot where he wanted to be buried, was impassable. So Olinger’s Mortuary, where he was initially interred, kept his remains in a cold storage vault for six months – embalming it six times – until the road up to the Lookout Mountain was made passable, and his burial site could be prepared.

On June 3, 1917, Buffalo Bill’s remains were carried to the summit of Lookout Mountain in Golden, Colorado, on the edge of the Rocky Mountains. Mourners and the curious arrived on special trains that ran from Denver to Golden. A steady stream of cars clogged the roadways into Golden and special buses shuttled people up the recently completed Lariat Trail-perhaps Colorado’s first traffic jam. The Lookout Mountain Park Funicular saw its busiest day ever.

Lookout Mountain for the internment

At three in the afternoon Buffalo Bill was laid to rest in a full Masonic burial service, under the auspices of Golden City Lodge Number 1. The front page of the Colorado Transcript reported: “With solemn and impressive Masonic burial rights, the Golden lodge of Masons, in the presence of 15,000 people conferred the last honors over the remains of Buffalo Bill.

The casket of solid metal was lowered into a grave blasted from the eternal granite. The site was one that the old scout himself would have selected, on the lofty eminence commanding the mountains and plains he loved so well. A poem dedicated to the sleeping scout was read by Jay J. Bryan of Golden. A farewell service followed, which was conducted by the entire body of Masons.”

As the infamous Buffalo Bill Cody awaited his final burial, Colorado and Wyoming started a heated feud over one of America’s most famous men. Wyoming claimed that Cody should be buried there, citing an early draft of his will that said he intended to be buried near Cody. Colorado cried foul, since Cody’s last will left the burial location up to his widow, who chose Lookout Mountain. Rumors even began to circulate that a delegation from Wyoming had stolen Cody’s body from the mortuary and replaced it with that of a local vagrant.

In part to stop the rumor mill, Cody was finally buried in an open casket on Lookout Mountain. 15-25 thousand (depending on which articles you read) people went to the mountaintop to bid him farewell before he was interred. To prevent theft, the bronze casket was sealed in another, tamper-proof case, then enclosed in concrete and iron.

Yet his rocky grave was anything but safe. In the 1920s, Cody’s niece, Mary Jester Allen, began to claim that Denver had conspired to tamper with Cody’s will. In response, Cody’s foster son, Johnny Baker, disinterred the body and had it reburied at the same site under 20 tons of concrete to prevent potential theft. (Allen also founded a museum in Wyoming to compete with a Colorado-based museum founded by Baker.)

The saga wasn’t over yet. In 1948, the Cody, Wyoming American Legion offered a $10,000 reward to anyone who could disinter the body and return it to Wyoming. In response, the Colorado National Guard stationed officers to keep watch over the grave.

Since then, the tussle over the remains has calmed down. Despite a few ripples—like a jokey debate in the Wyoming legislature about stealing the body in 2006—Buffalo Bill still remains in the grave. If you believe the official story, that is. In Cody, Wyoming, rumor has it that he never made it into that cement-covered tomb after all—proponents claim he was buried on Cedar Mountain, where he originally asked to be interred.

A remarkable man, with a remarkable story – even in death.

Up next, a short (promise!) Special Edition on Annie Oakley – yet another fabled character from our past. What an exceptional woman she was!