Bayou Segnette State Park, Westwego, Louisiana

The LORD was with Joseph and he prospered, and he lived in the house of his Egyptian master. When his master saw that the LORD was with him and that the LORD gave him success in everything he did, Joseph found favor in his eyes and became his attendant. Potiphar put him in charge of his household, and he entrusted to his care everything he owned. …. the household (and all that was Potiphar’s) was blessed …. because of Joseph. He (Potiphar) did not concern himself with anything except the food he ate. ~ Genesis 39:2-6a Compare Joseph’s life to that of Judah’s. Even though Joseph was sold by his brothers and enslaved, he kept the Lord close at hand, and thus, not only did God bless Joseph (despite his circumstances), He also blessed those around him. How do you think you would’ve faired in Joseph’s shoes? Would you have been bitter and angry, turned your back and cursed God? Would you have been accepting and made the most of it, always doing your best (“as working for the Lord”, Colossians 3:23) and keeping a tight grasp on your faith; believing His plan is perfect?

It’s always good when moving day isn’t very exciting. The only issue we had was encountering a two-mile backup, but since my brother, David taught us to use Waze, we were able to find a way around it. Good thing it worked out because we both forgot the very important rule of checking if roads are safe for trucks! Things like narrow or tightly curved roads, or sharp inclines or declines, or low bridges are great big huge no-no’s for vehicles our size!

The only other thing of note? Somehow or other, we crossed the Mississippi – – twice – – as we headed due west. Guess it’s as crooked as all those ‘esses’ in its name!

(for those of you are are familiar with the Steve Martin movie) lol

There’s one exit near the end.

So once you’re on, you’re on for a good long while. : )

People were kind enough to let Blaine get to the exit.

It was after we were committed that we thought of the possible problems.

Too late now!

Even though it doesn’t look like it, traffic is moving quickly.

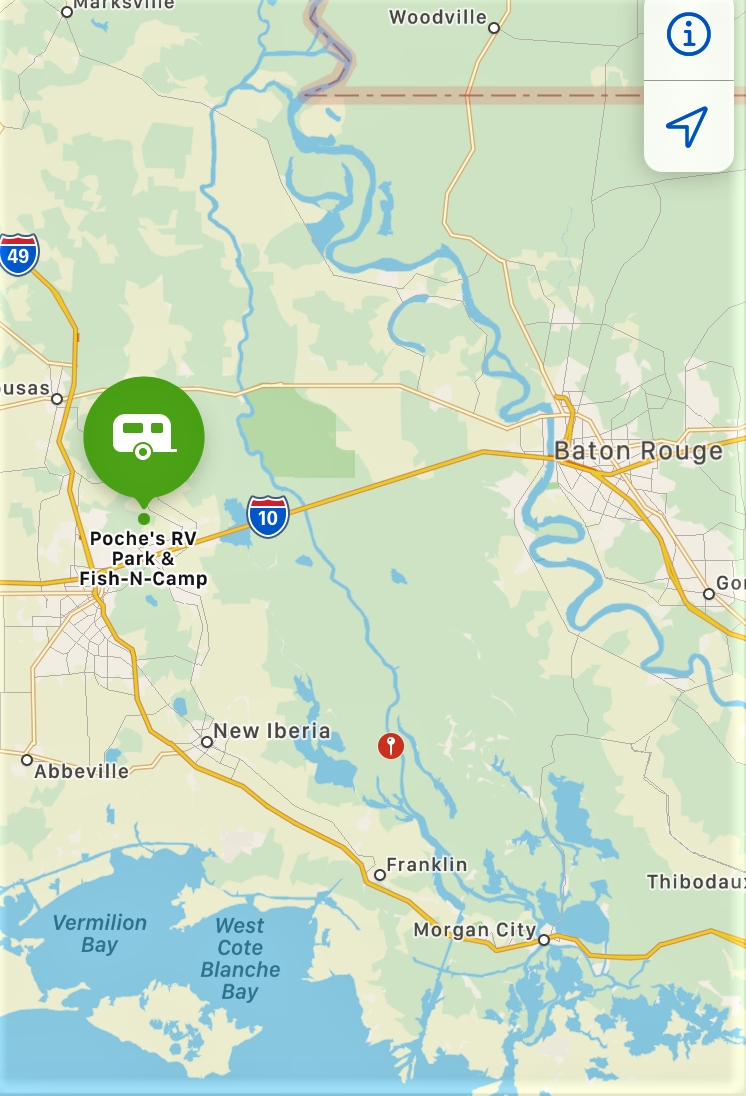

Poche’s RV Resort, Breaux Bridge, Louisiana

Those of you with our itinerary are no doubt surprised to discover we’ve veered off course. Turned out that Blaine didn’t have the reservations actually made for these three days, and after I sent it out – and even beyond – he made the reservation for Poche’s in Breaux Bridge.

Now I know you can pronounce ‘bridge’, but how about the rest? Wanna give it a try before I help you out?

The first is po (with a long ‘o’ like “potential”) SHAY’s. The second is bro (with an ‘r’ and a long ‘o like “broken”). Poshe’s in Breaux Bridge. So how badly did you mangle it? Probably no worse than we did. We kept calling the campground ‘Pooches’ and leaving out the ‘r’ in Breaux, making it ‘bow’. 😊

For the beauty of the earth, for the glory of the skies,

Lord of All to Thee we raise, this our hymn of grateful praise!!!

It’s hard to tell from the picture, but everything was covered in frost this morning!

It was 34 out there!

Sunday morning, we worshiped in the same church we visited twice for their Christmas program a few years back. Its Cornerstone located either in Lafyette or Breaux Bridge. We’re not sure, because the address says Lafyette, but the pastor mentioned being in Breaux Bridge. Hmmmmm……

One of their announcements was for their upcoming men’s Beast Feast! It’s $10 and all-you-can-eat! Plus, they’re giving away a shotgun and grill. How many churches give away shotguns? 😊 They were looking for more beastly donations. Got anything you’d like to share?

Even though we knew none of the worship music, God used the words to speak loud and clear to our hearts in our present circumstances, focusing on God’s faithfulness. We were a bit surprised when one of the song leaders sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, but it turned out to be requested by the pastor as a lead into the beginning of a new sermon series called “Over the Rainbow”. God also spoke to us through his message. He is sooo very faithful! Why do we so often forget that?

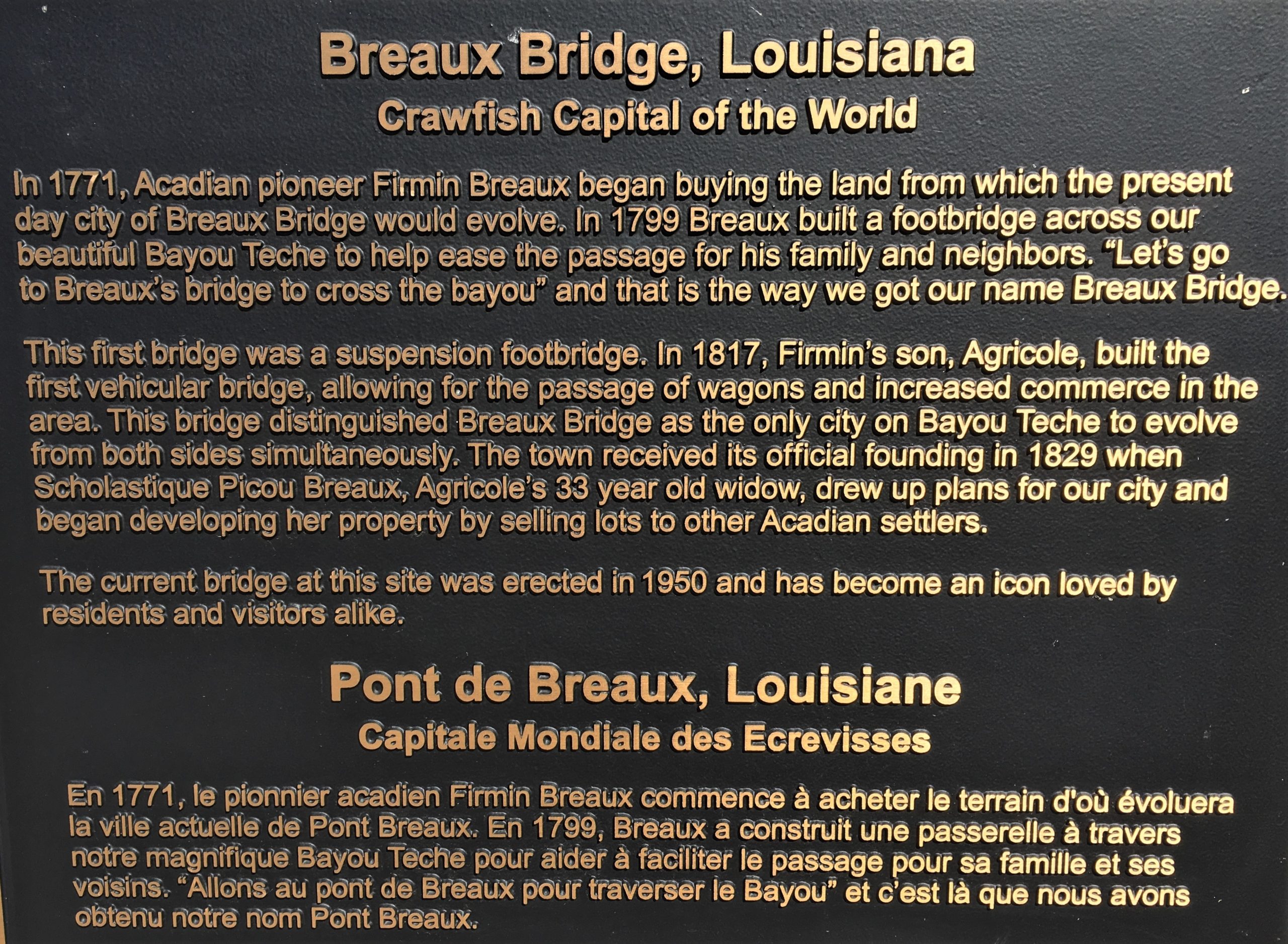

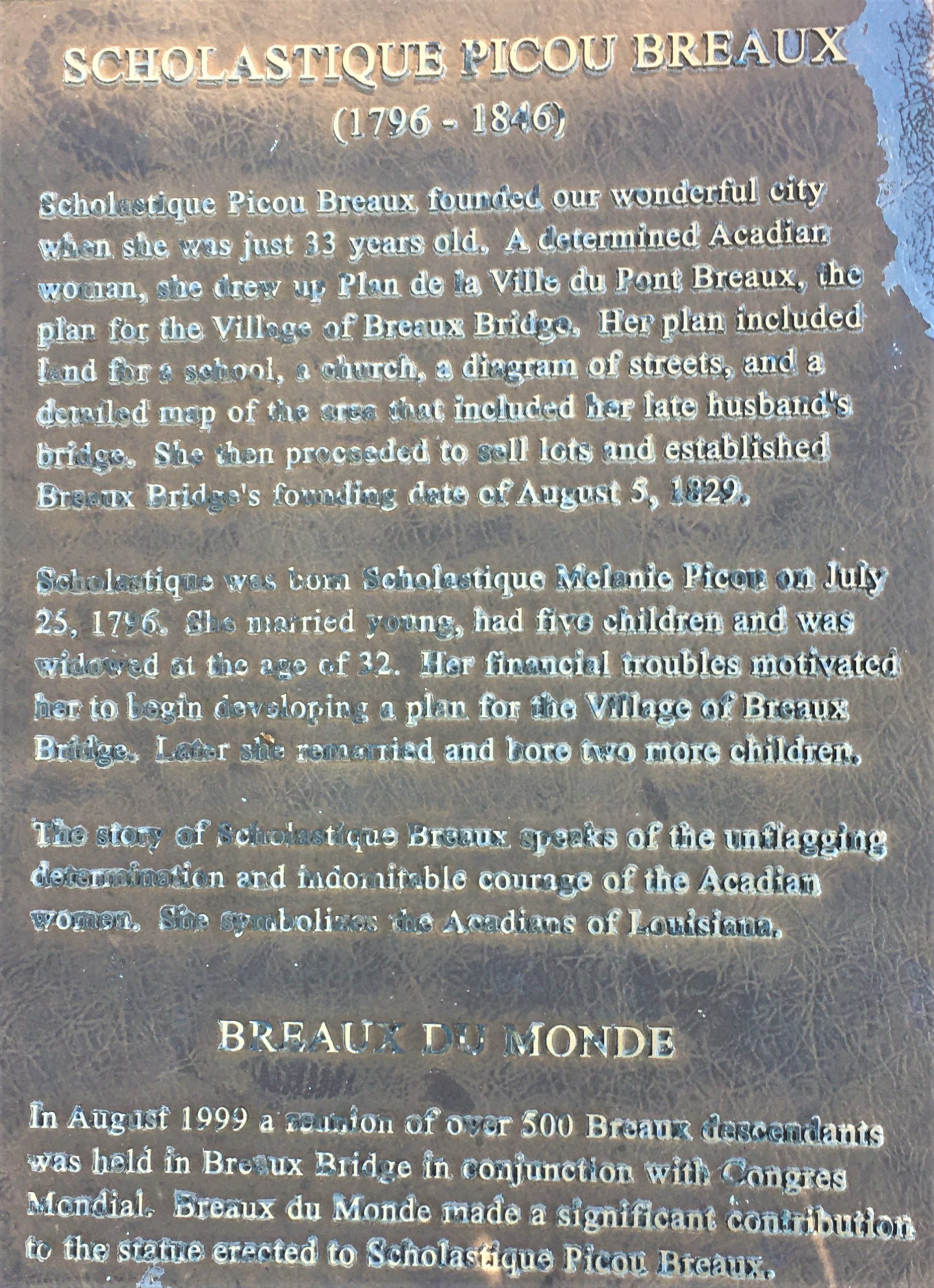

After church, we changed clothes and headed out for a self-guided walking tour of Breaux Bridge. Their website provided a printable history of the buildings, etc., around town. It was a beautiful, sunny day, and we enjoyed our walk very much. Here’s a few of the things we saw, along with the descriptions given on their walking tour papers:

This bridge was built after the previous bridge collapsed.

Note the painted crawfish on top the bridge, celebrating our legacy as the “Crawfish Capitol of the World”.”

It presently operates as a bed and breakfast inn.”

“Before a Catholic Church building was built in Breaux Bridge, residents would meet under the tree for mass.

Born in 1893, Huey Long of Louisiana worked as a traveling salesman, earned a law degree in a single year, and then entered public life as a railroad commissioner in 1918. Drawing on a political power base that he built among Louisiana’s small towns and rural districts, he became governor in 1928. Fearlessly, he took on the moneyed interests of Baton Rouge and Wall Street, calling for a massive redistribution of wealth. In 1932, amidst the Great Depression, Long was elected to the Senate, where he gained a national following with his “share-our-wealth” plan and his “Every Man a King” philosophy. Once described as the “most colorful, as well as the most dangerous, man to engage in American politics,” Long was known in the Senate for his filibustering and his flamboyant oratorical style. Nicknamed the “Kingfish,” his ambitions soon turned to the White House. In 1935, at the height of his popularity, Huey Long was assassinated in Baton Rouge. ~ senate.gov

According to Britannica, he had an unprecedented executive dictatorship that he perpetrated to ensure control of his home state. Long was at the height of his power when assassinated by Carl Austin Weiss, the son of a man whom he had vilified. The Long political dynasty was carried on by his brother Earl K. Long, who served as governor (1939–40, 1948–52, and 1956–60), and his son, Russell B. Long, who served in the U.S. Senate from 1948 to 1987.

“features a 2-sided wrap around gallery, a large bay room and a large dormer above the gallery with a door and private balcony. An operational windmill once stood on the property making this the first home in the parish to have running water. It is presently a private residence.”

BTW – a ‘parish’ is like a county in Louisiana.

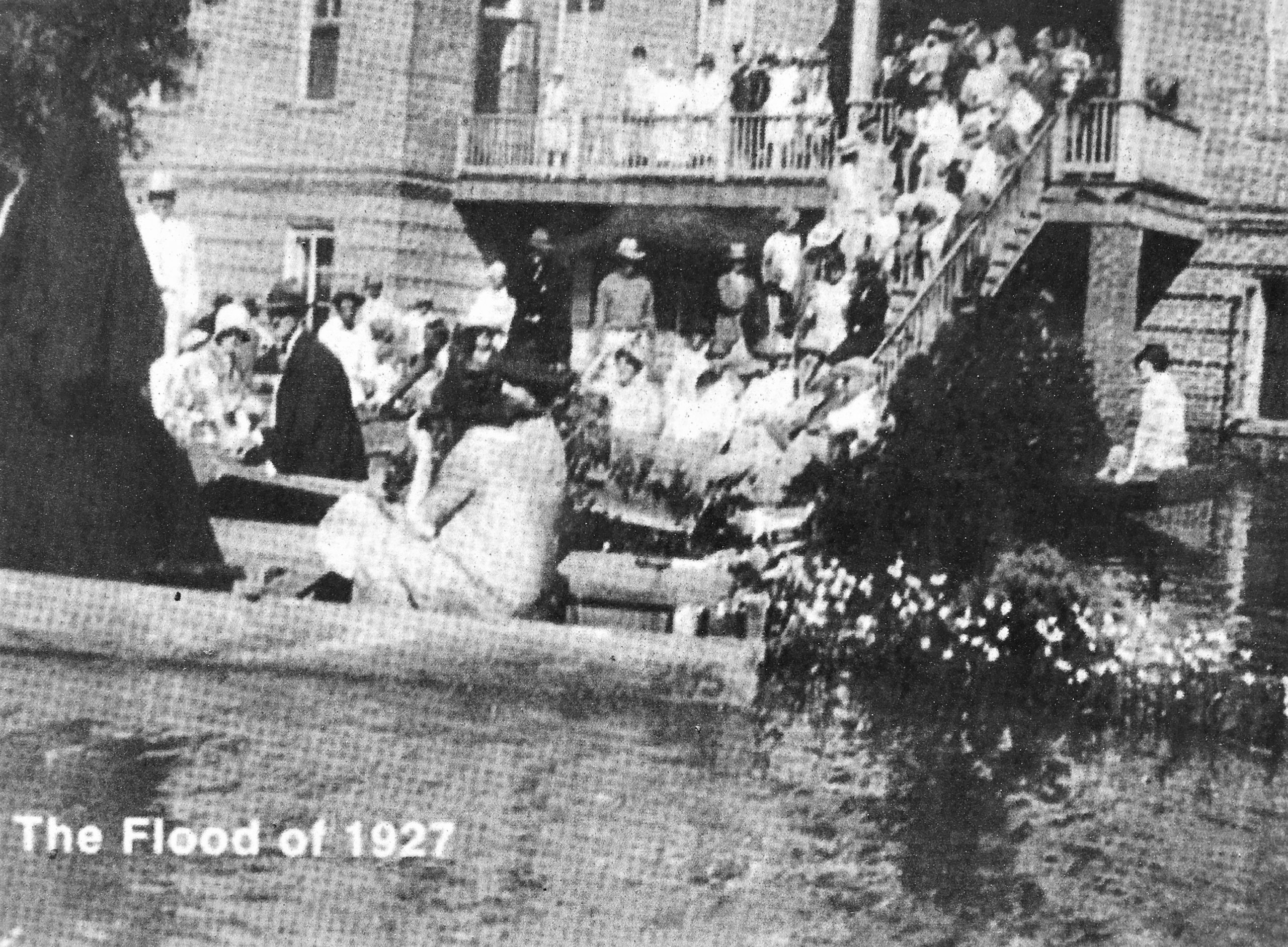

“This is the water mark for the flood of 1927.”

The lounge was known by locals for its tradition of being a “men only” establishment.”

It was built by Leonce Ransonet for his wife. The home is a 2-story Eastlake with a wrap-around gallery. It features a 2-story octagon tower with fish scale siding. It presently serves as a private residence.”

I don’t know what ‘fish scale siding’ is.

Looking for something a little faster paced, we drove over to a place where we kayaked before. As soon as I saw it, it remembered the fun we had paddling around the Cedar trees! Unfortunately, it was too late in the day, and we were improperly dressed to go out today. ☹ And so. We walked.

If I remember correctly, dinner was a doctored up $5 Walmart pizza.

Our final day contained mostly domestic stuff – laundry, planning for and shopping for the next week’s groceries because Blaine has informed me that there are no grocery stores close to where we’ll be (which means that no matter how much time I spent planning and pouring over my shopping list, I’ll forget something), and whatever stuff Blaine has to do outside to keep us up and running properly.

Then we went to a middle-of-the-afternoon meal at Poche’s Restaurant and Market. Yep. They own that too! It was highly rated, plus there were always tons of cars in the parking lot. It’s not a fancy place, but the catfish we ordered was excellent, and they gave us four huge pieces of fish! We took some home for sandwiches another evening. Their homemade potato salad was also excellent! I should look into how to make Louisiana potato salad. It’s not like we’re used to, but it’s very good. Most of the potatoes are mashed, and it’s thick enough they serve it as a rounded scoop. Sorry, no pictures, but I found the following on-line. It’s pretty close to what we had.

After dinner, we browsed the market, settling on a box of frozen boudin balls to try. I’ll let you know how they are once we try them. Maybe this upcoming week! Although that’ll put a kink in my dinner planning . . . .

A brisk walk around our campground, and then another night of the Beijing Olympics.

Tomorrow, Texas!

The Flood of 1927 was described by U.S. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover as “the greatest peace-time calamity in the history of the country.” It inundated 16,570,627 acres (about 26,000 square miles) in 170 counties in seven states, driving an estimated 931,159 people from their homes. The Mississippi River remained at flood stage for a record 153 days. The flood caused more than $400,000,000 in losses; 92,431 businesses were damaged and 162,017 homes flooded. According to various estimates, there were between 250 and 500 flood-related deaths. In Louisiana alone, 10,000 square miles in 20 parishes went underwater. The congressional response to the devastation, the 1928 Flood Control Act, had far-reaching social, political, and physical consequences in Louisiana and throughout the Mississippi River valley.

The prelude to the flood began in August 1926, when rainstorms began to swell streams in eastern Kansas, northwestern Iowa, and part of Illinois, all of which fed into the Mississippi River. In December, heavy rains in Oklahoma, Arkansas, and northern Louisiana filled the Arkansas and Red rivers. During that fall, record rainfalls continued throughout the Mississippi River valley. By the end of January, major tributaries such as the Ohio River were overflowing their banks. In earlier times, this would not have been the problem it was in 1927; the Mississippi River and its tributaries once overflowed into natural drainage areas. But in the late 1800s, the Mississippi River Commission adopted a “levees-only” policy, which entailed the construction of levees that ran almost the full length of the river. While these levees prevented flooding for a period, they proved unable to withstand the floodwaters of 1927.

Threat to New Orleans

Through the early spring of 1927, the rains continued and the flood pushed downriver toward Louisiana. New Orleans received 11.16 inches of rain in February—compared to an average of 4.4 inches for the month—and steady rainfalls thereafter. Then, on Good Friday, April 15, 1927, more than 14 inches of rain fell on New Orleans in a single day, disabling the pumps that normally drained the city. The levees were not breached; river water did not rush in. Instead, the levees held the rainwater inside the city. That downpour also added more water to the Mississippi River as it rushed past New Orleans. The levees there were under pressure from both sides, and concerned citizens began to buy boats and stockpile food. As heavy rains continued in the Mississippi River drainage area above Louisiana, more than 20,000 men were put to work sandbagging levees between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

The threat continued to worsen, however, and state government officials believed the levees would inevitably break. If the break happened below New Orleans, it would relieve pressure and spare the city from massive flooding. An upstream break, on the other hand, would send a disastrous flood into New Orleans. Despite strenuous objections from people living downstream, Governor O. H. Simpson and his advisors acquiesced to a plea from New Orleans civic leaders to blast a breach in the levee. This would give the flood a shortcut to the sea and drop the river level at New Orleans, at the cost of flooding further south. Engineers chose a westward loop in the river at Caernarvon and began blowing the levee apart on April 29. Over the next ten days they used thirty-nine tons of dynamite to open a channel that released 250,000 cubic feet of water per second from the river.

For two days before the dynamiting began the National Guard and major retailers from New Orleans sent convoys of trucks to evacuate the 10,000 residents whose homes and livelihoods would be washed away when the levee was breached. Most of the refugees went to stay with relatives. Those who had no place to go were brought to a warehouse in New Orleans. White people were housed on the fifth floor, black people on the sixth. All had been promised full compensation for their losses, but the lucky ones would get an average of only $274 each, and thousands of them would get nothing.

Part of that was because nobody realized how much would be washed away. The financial leaders from New Orleans estimated that claims against a fund set up to compensate the victims would be between $2 million and $6 million. Instead, they amounted to $35 million, and there wasn’t enough money to go around. Additionally, the fund had to bear the expense of feeding the refugees at a cost of $20,000 a week. Refugees had to file a claim to receive compensation under a complicated system that divided payments into various categories, provided that no partial payments could be made, and without legal representation.

The refugees were caught between a system of legalities they did not understand and marshes still filled with water that kept them from going home. Most settled for pennies on the dollar, and practically all of them remembered that it was a man-made catastrophe that put them where they were. Adding to their anger, a natural breach of the levees subsequently eased pressure on the New Orleans levee; the blasting had been unnecessary. Though New Orleans had been spared, other parts of southern Louisiana were still in trouble, particularly in the Atchafalaya River and Bayou Teche basins to the west of the city.

Inundation of Southern Louisiana

The Atchafalaya River forks away from the Mississippi River at Simmesport in Avoyelles Parish. Though it and its tributaries were lined by levees, they were filled to overflowing, and part of the Mississippi River sought this shorter, straighter course to the sea. Smaller levees had begun to break in northern and central Louisiana in mid-May, but a disastrous break in the Atchafalaya River levee came on May 17 at Melville in St. Landry Parish. River water poured through the breach and began to rush to the south, soon joined by floodwaters caused by a break in a Bayou des Glaises levee to the north of St. Landry, in Avoyelles Parish.

The two floods met just north of Port Barre in St. Landry Parish on May 18. They combined to send an estimated 1.3 million cubic feet of water per second roaring to the south. The flood inundated Arnaudville at the St. Landry-St. Martin Parish line on May 19; Breaux Bridge and St. Martinville in St. Martin Parish two days later; then New Iberia and Jeanerette in Iberia Parish; and Franklin and Morgan City in St. Mary Parish. By the end of May, sixty thousand refugees were either in southern Louisiana camps or receiving Red Cross aid elsewhere. Thousands of cattle drowned and farm crops were wiped out as southern Louisiana turned into a lake 200 miles long and 50 to 100 miles wide. It was not until June that the floodwaters began to drain into the Gulf of Mexico

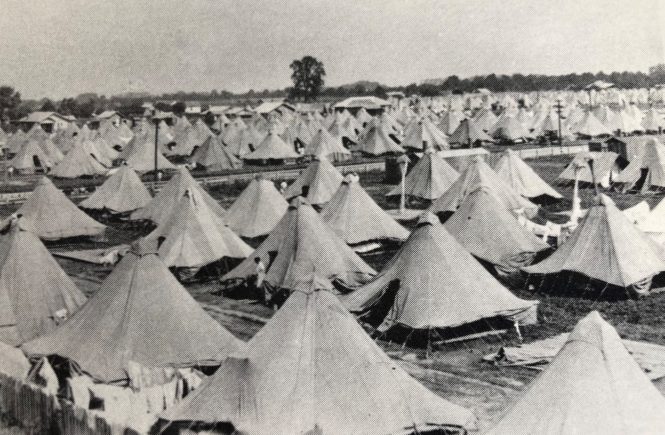

Once again, housing had to be found for tens of thousands of refugees who had no relatives to stay with. The Red Cross and local relief organizations set up tent cities and makeshift housing in Marksville, Mansura, Baton Rouge, Opelousas, Crowley, New Iberia, and elsewhere. Some twenty thousand people were housed at Lafayette alone. Parishes set up “rehabilitation committees” to find food and shelter for the displaced families.

When the water finally subsided, the Red Cross provided seed, tools, and rations to farm families facing the daunting task of surviving the winter and starting a new crop in the spring. Some six hundred prefabricated cabins were sent to St. Martin Parish and more like them elsewhere to temporarily replace destroyed housing. At the end of August 1927, an anonymous Associated Press reporter touring the Teche region was able to write, “Little farmhouses, bearing brown watermarks at various heights according to the depth of the water reached, are once more occupied, and some of the farmers are plowing in preparation for new plantings. A few have crops already growing, and cane and corn are making a brave attempt to put forth fruit despite the late start given them.”

Flood Policy Revision

The Flood of 1927 showed that levees alone would not solve the problem of flooding on the Mississippi River and forced the federal government to reconsider its flood control policy. As a result, huge tracts of lowland, called spillways, were set aside in south central and southeastern Louisiana. Massive gates were constructed to allow excess water to be diverted into these areas in times of severe flooding. Whole communities, such as Bayou Chêne, built upon a ridge in the Atchafalaya River basin, had to be abandoned because they were in the path of the floodwaters that might be diverted.

The flood drove many tenant farmers, most of whom were African American, off their land and, in many cases, out of the region. They migrated by the thousands to Chicago, Detroit, and other northern cities, changing the urban landscape in those places. In addition, a stingy fiscal policy that offered little aid to the flood victim, implemented under Republican President Calvin Coolidge, drove many African Americans from the party of Lincoln into the Democratic party, where they continue to be a considerable part of the constituency today.

Since Hurricane Katrina inundated New Orleans and the parishes to its south, there have been inevitable comparisons between the two disasters. Each was caused more or less by a man-made breach of a levee. Each caused widespread dislocation of large numbers of people for many months. Each changed both the physical and political face of t he region and played a role in national affairs. Criticism over the handling of Katrina contributed in large measure to the decision by Gov. Kathleen Blanco not to run for reelection in Baton Rouge, and in lesser degree to a change of party in the White House in Washington. The Flood of 1927 opened the door for the populist Huey Long to make his first successful run for the governor’s mansion and played a substantial role in the selection of his party’s candidate for the presidency. Both calamities caused widespread dislocation of black people, the first adding to a migration to the major urban cities of the North, the second to cities such as Houston and Atlanta. Both caused disruptions of life in southern Louisiana for thousands of people that arguably could be outranked only by the destruction caused during the Civil War.