Bull Run Campground, Centerville, Virginia

Pharaoh asked the brothers, “What is your occupation?” “Your servants are shepherds, they replied to Pharaoh, “just as our fathers were.… We have come to live here awhile, because the famine is severe in Canaan and your servants’ flocks have no pasture. So now, please let your servants settle in Goshen.” ~ Genesis 47:2-4 And so, by freely admitting their vocation and asking to settle in Goshen, we will see that Pharaoh grants their petition – and even more (which we’ll get to tomorrow). Did you notice that it sounds as if they’re planning on leaving to return to Canaan once the famine is over? How often we make plans that God changes for His own Purpose! That’s why it’s such a good practice to check in with Him in our decision making. And to continue to do so as we move along through life. Speaking for Blaine and I, we ask Him frequently if this nomadic lifestyle is where He wants us to be. He’s not closed that door yet.

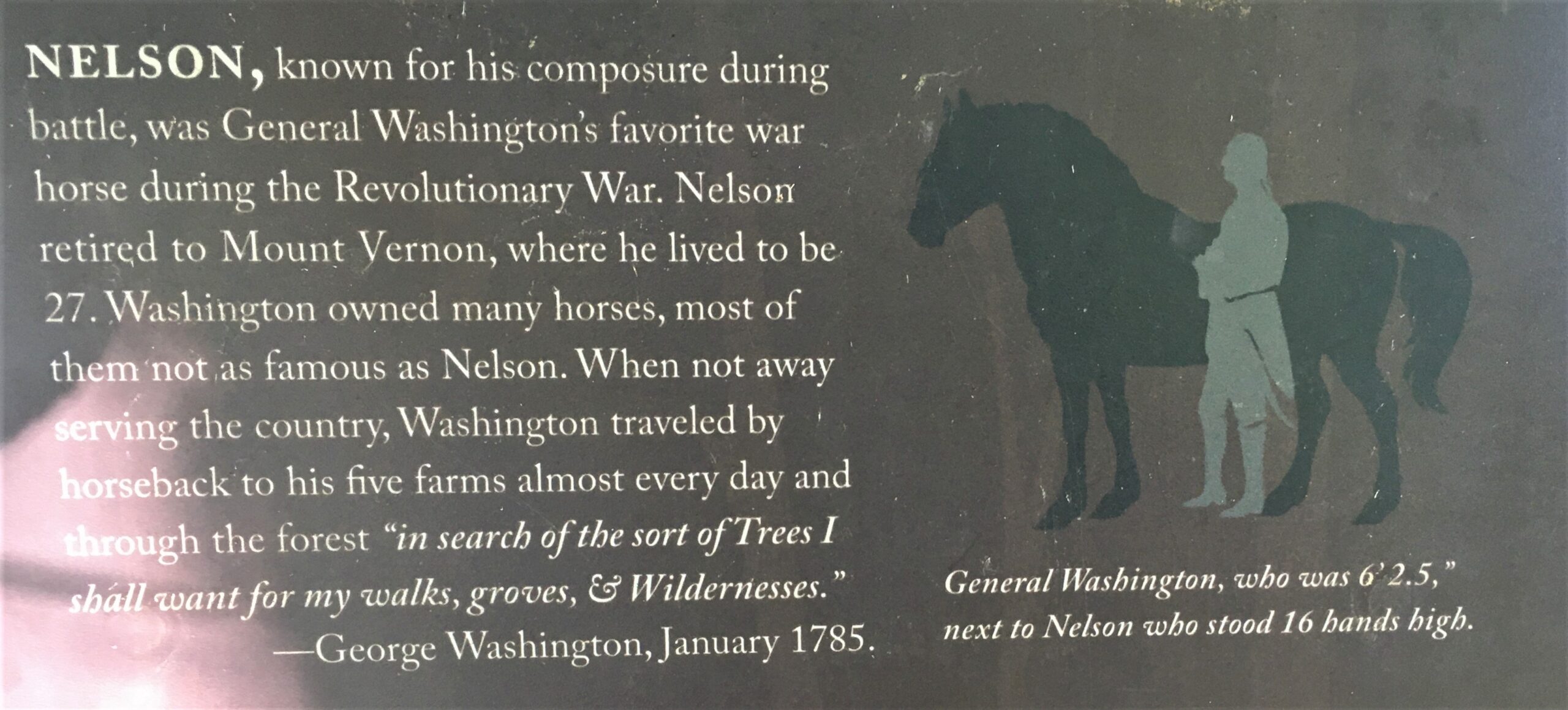

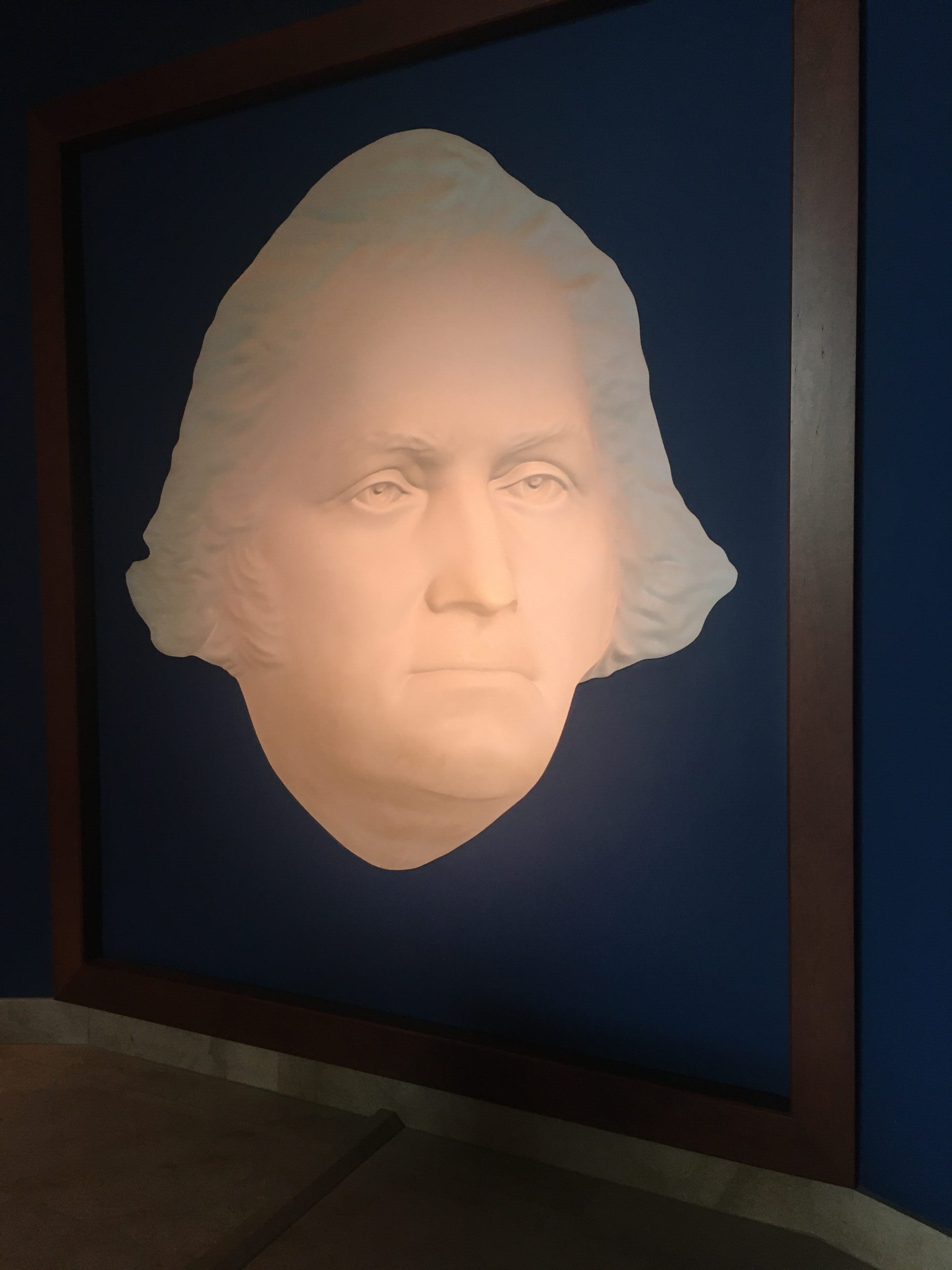

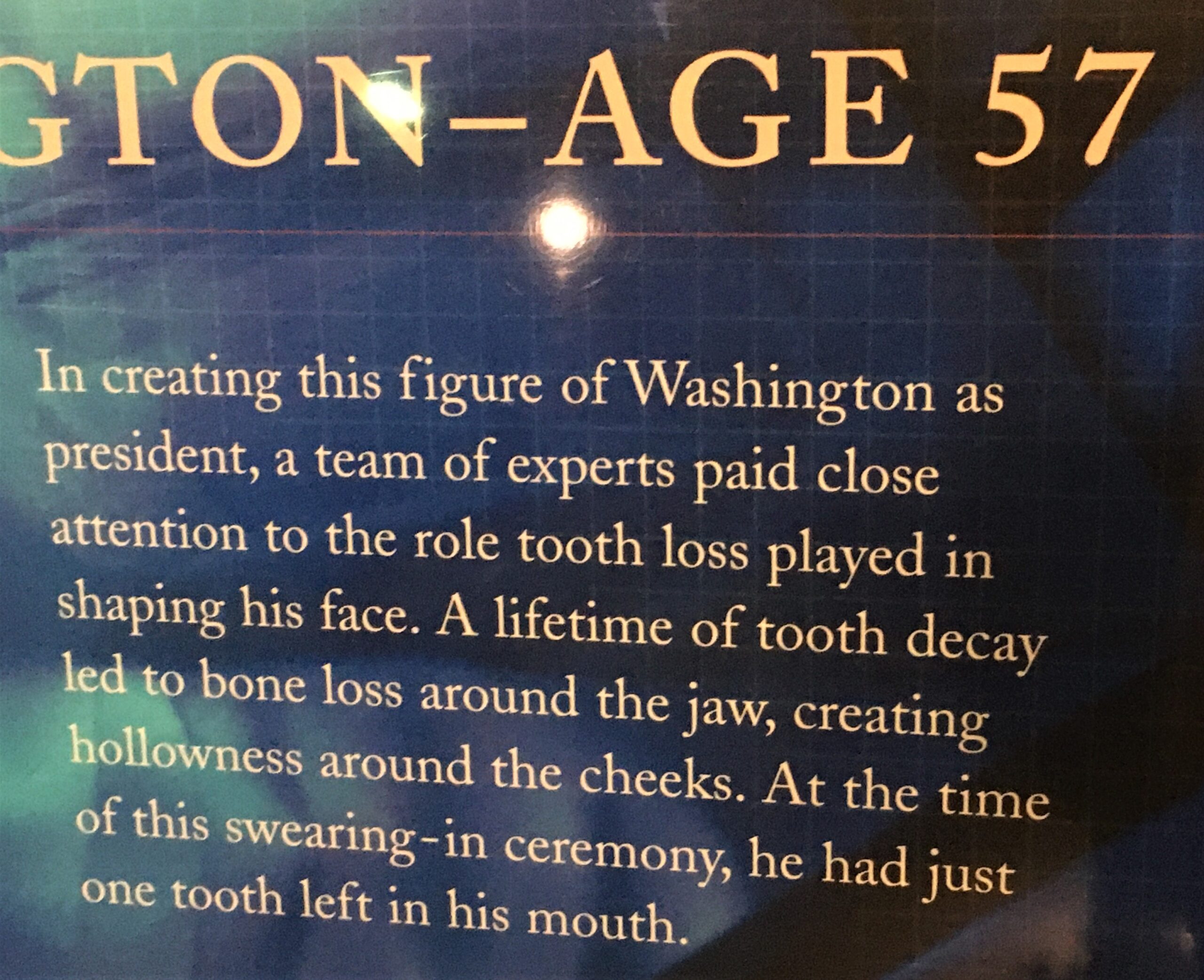

Wanna know one of the reasons I think men thought so highly of George Washington?

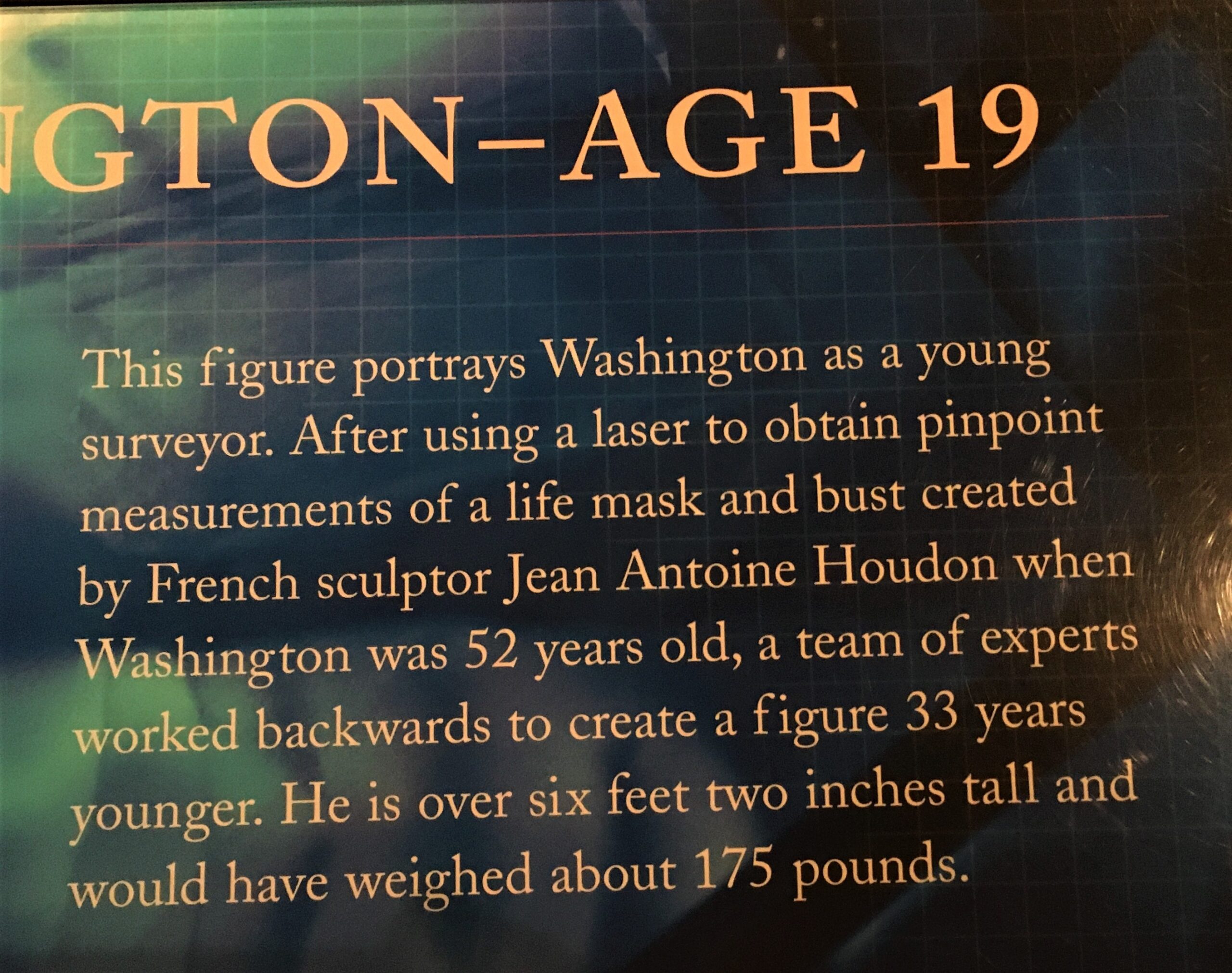

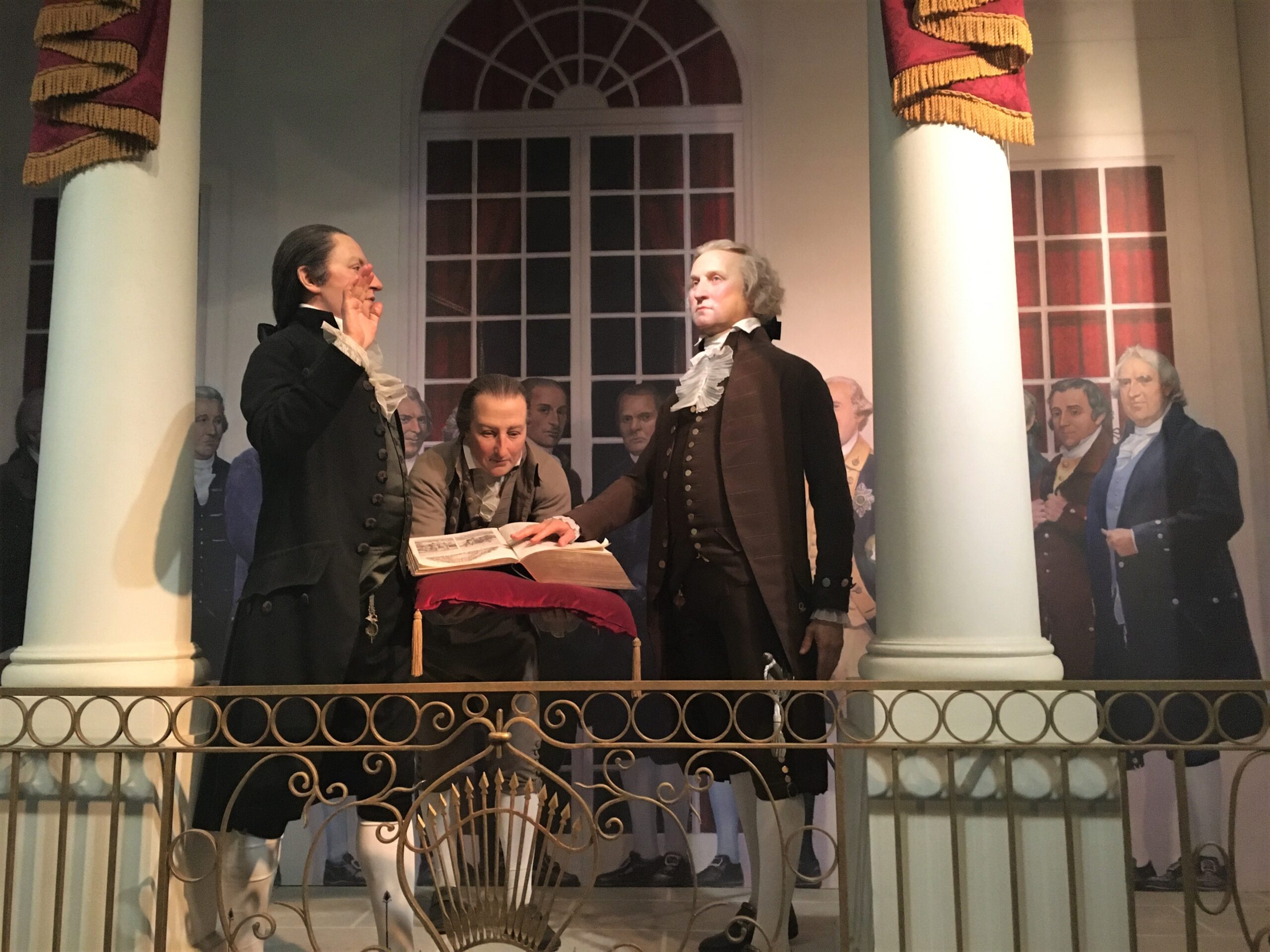

He was 6’2 ½”. During the Revolutionary era the average height of American men was 5’8”. American men in Revolutionary days also averaged three inches taller than their British counterparts – making them an average of 5’5”. That’s barely taller than me! That also means that Washington must have towered over the British, as well as his counterparts – sort of like those seven-foot-something guys who play basketball these days.

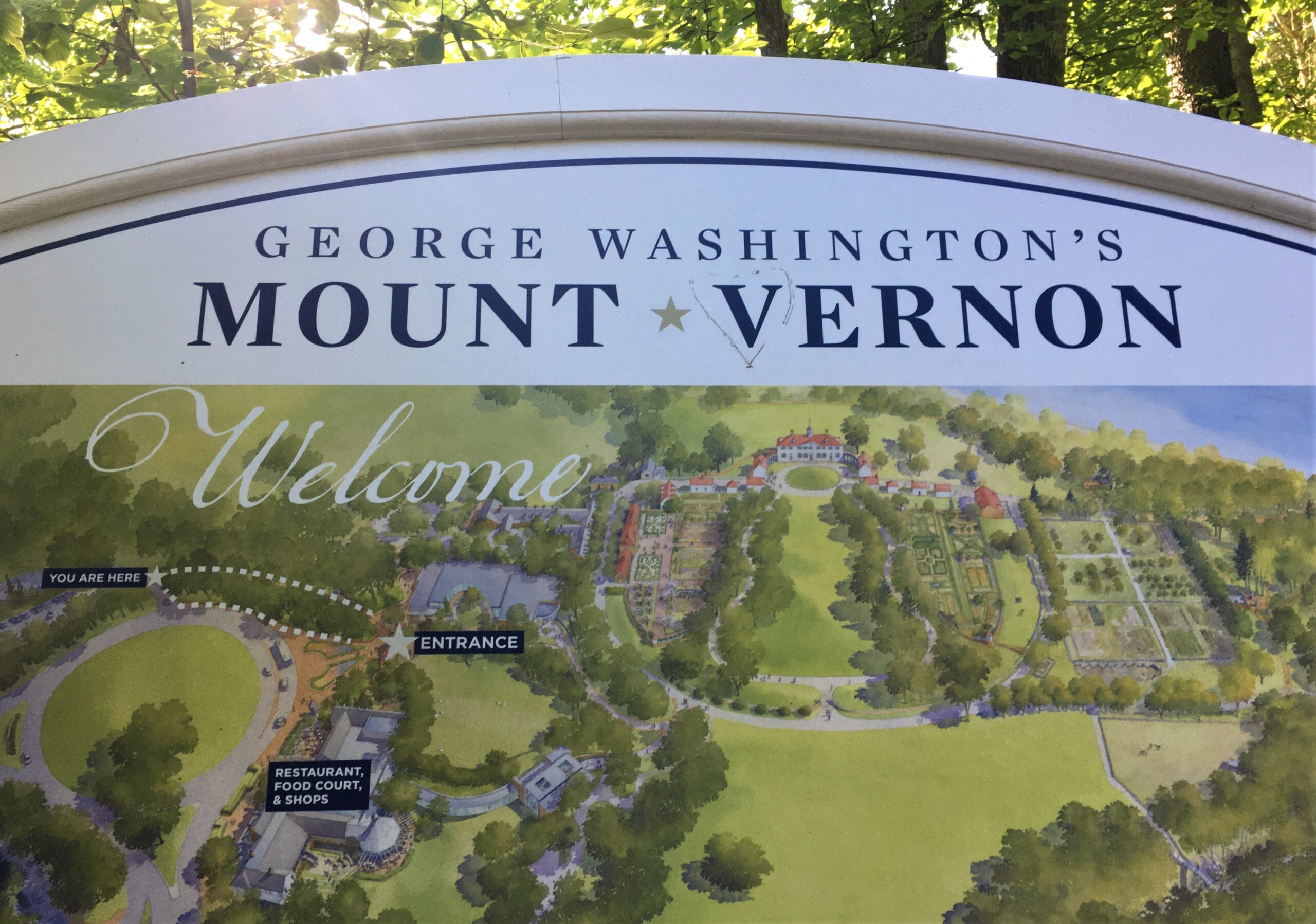

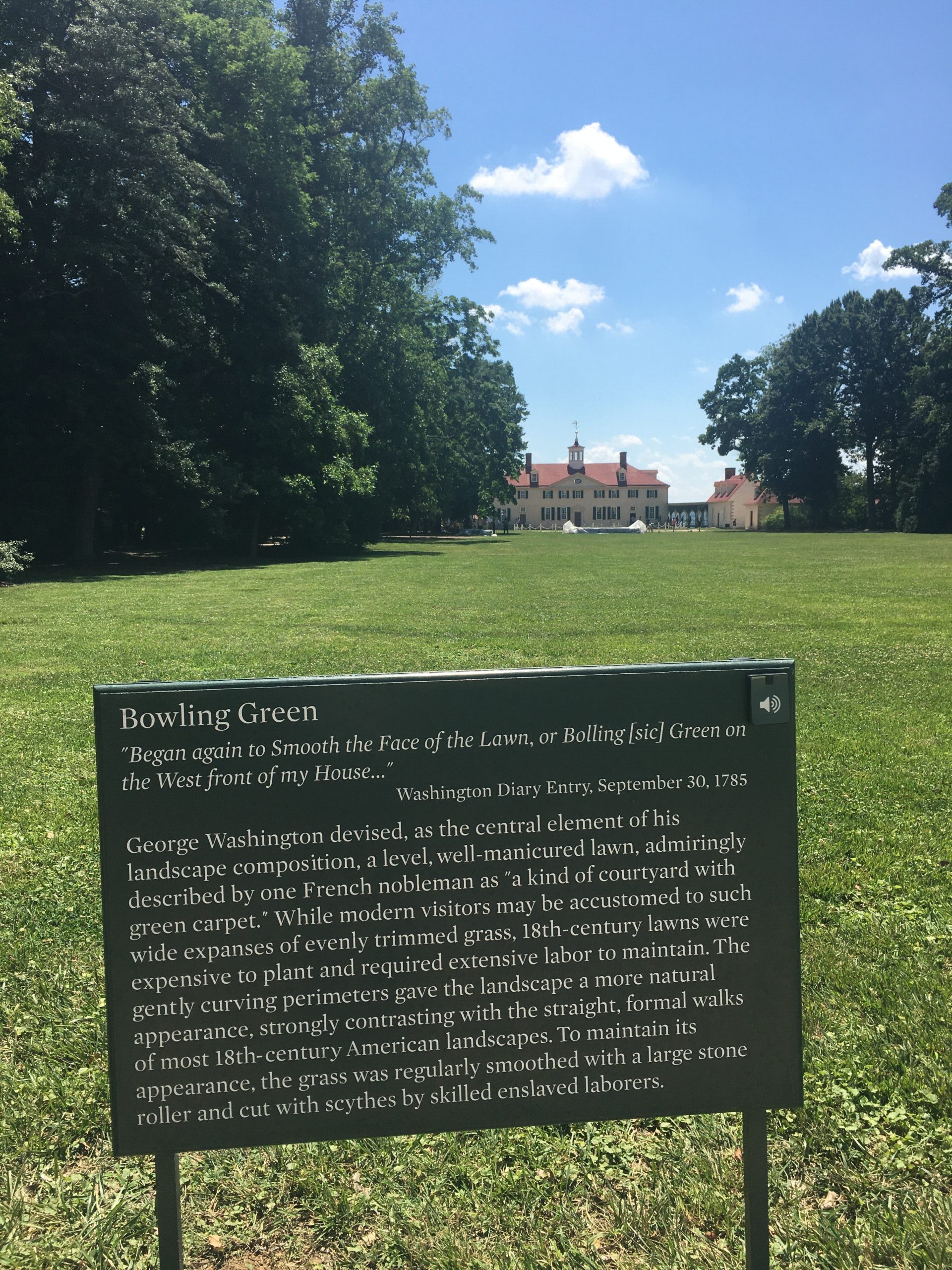

Today was spent at Mount Vernon, home to our first President. I somehow got myself embroiled in the history of the house, and took off for several hours exploring history. Actually, it was more like half a day! Sigh. . . . If you, too, feel the tug to look into the legacy of the house itself, you can read my Special Edition – Mount Vernon post coming up next.

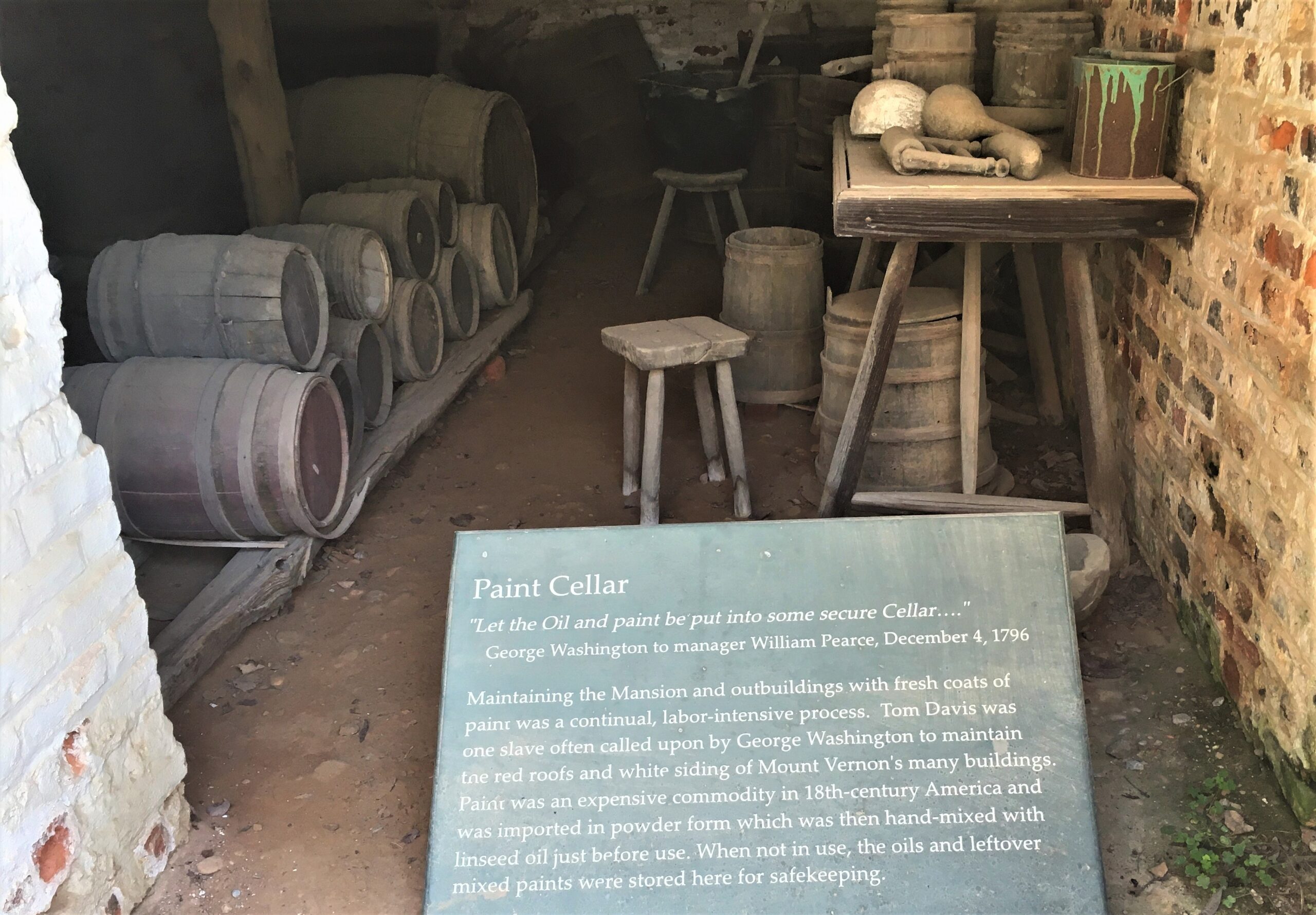

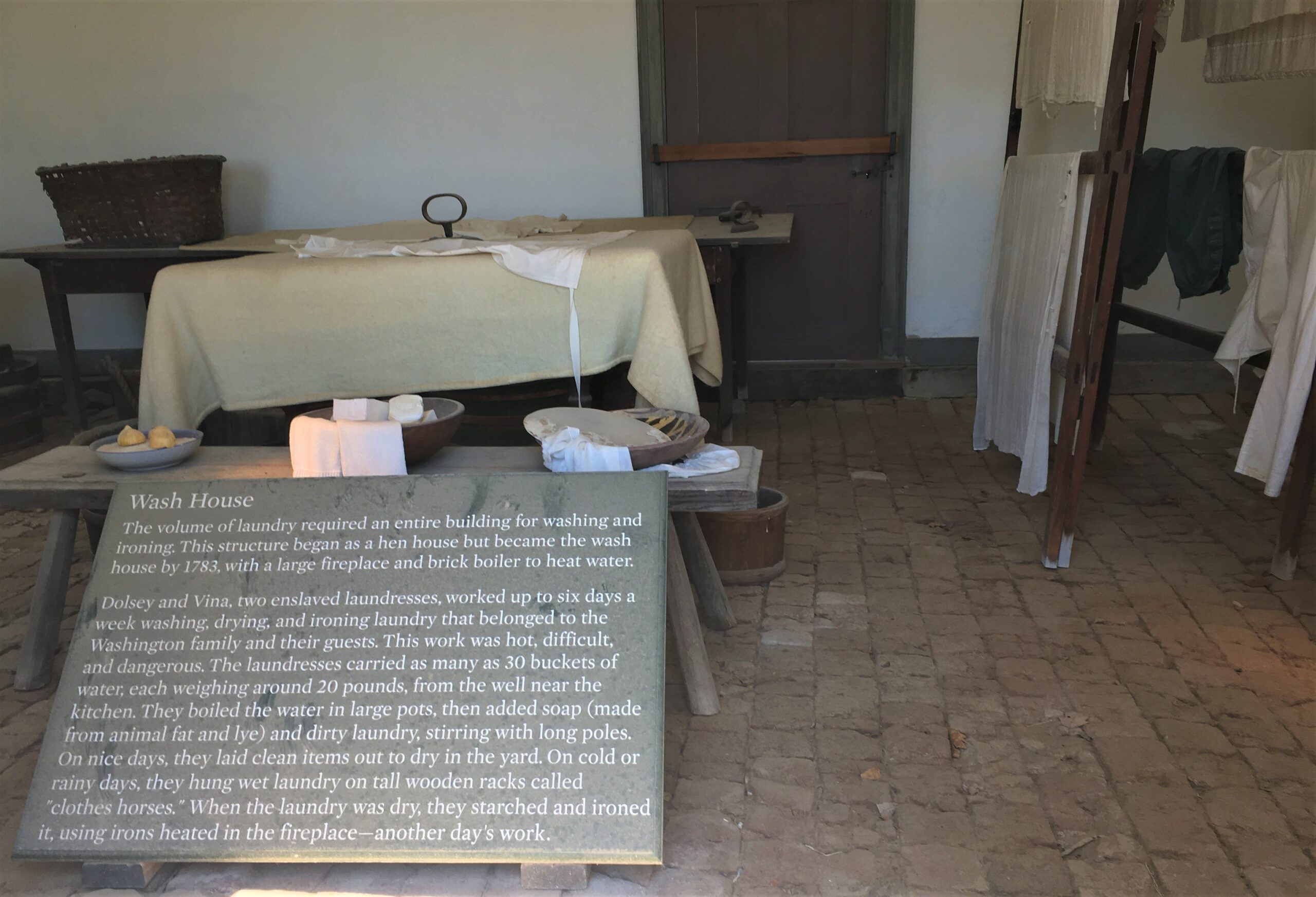

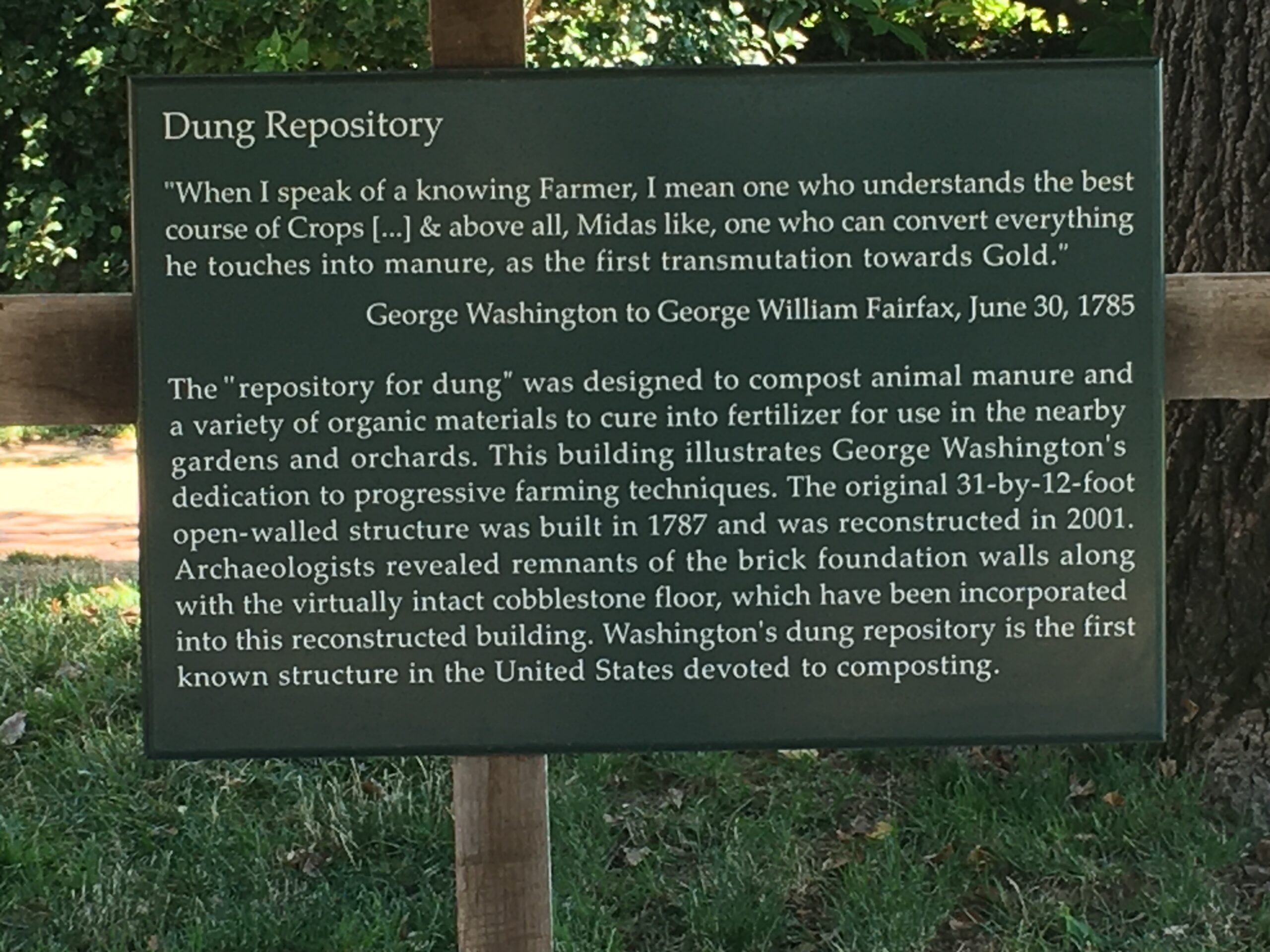

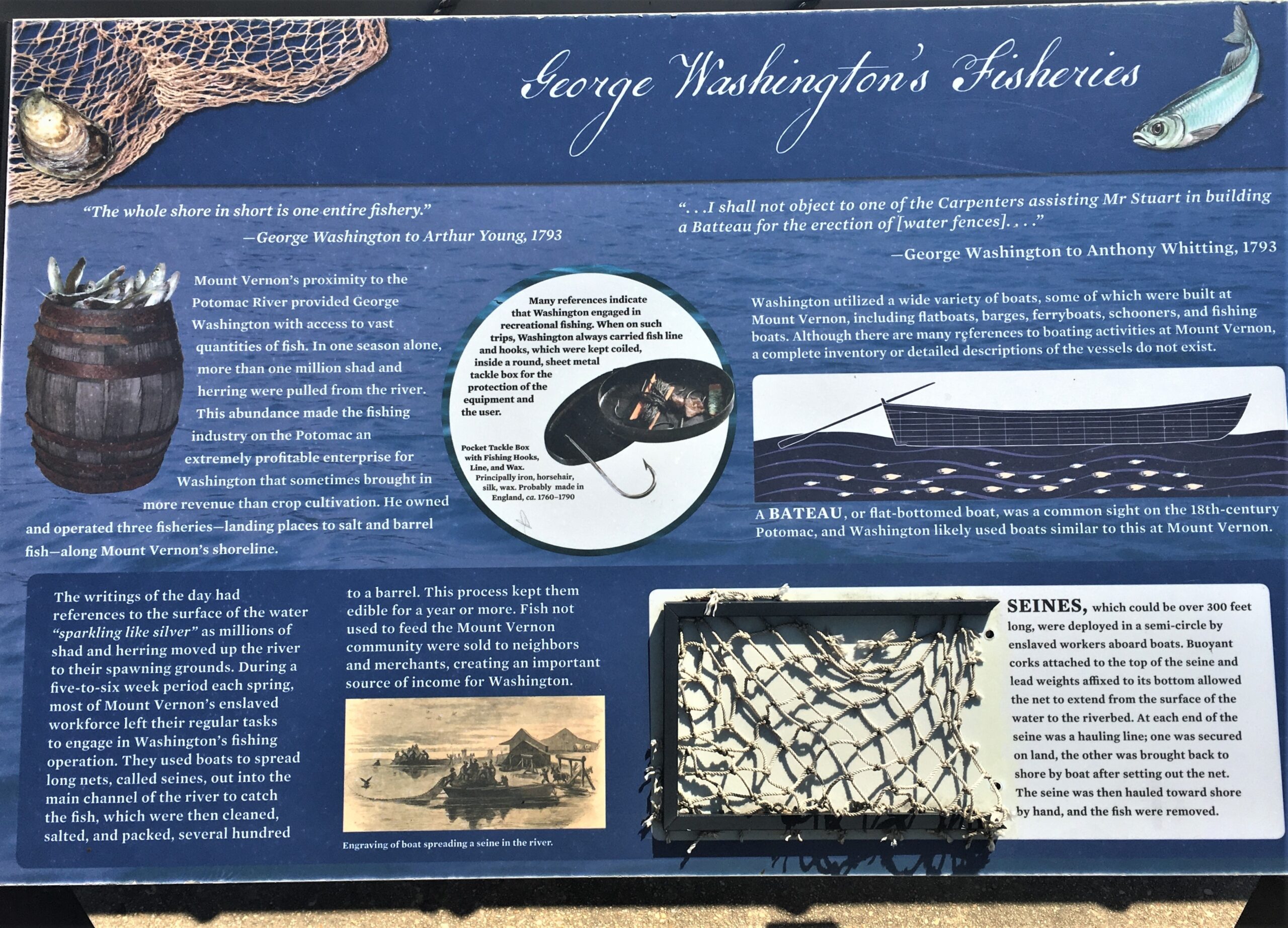

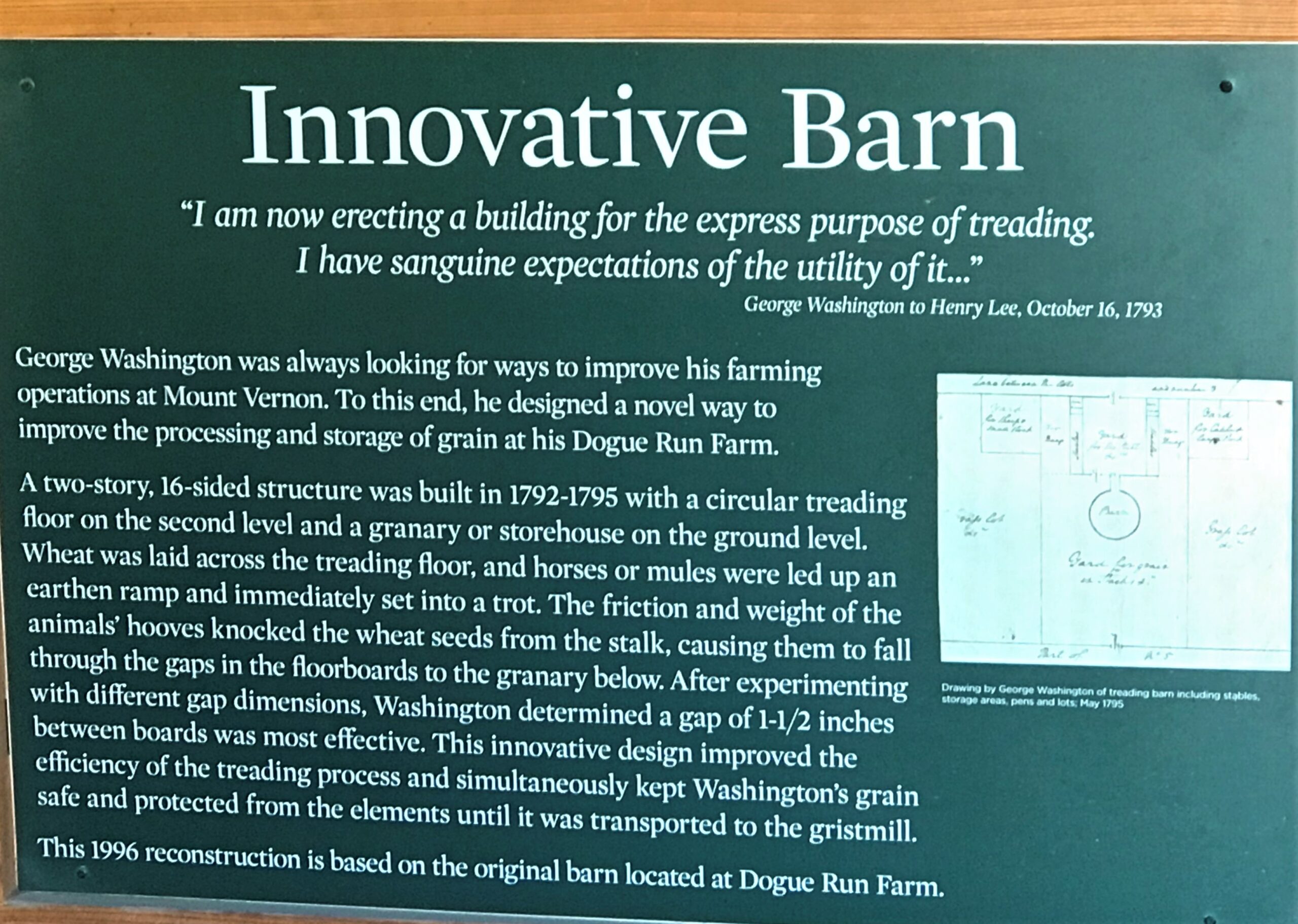

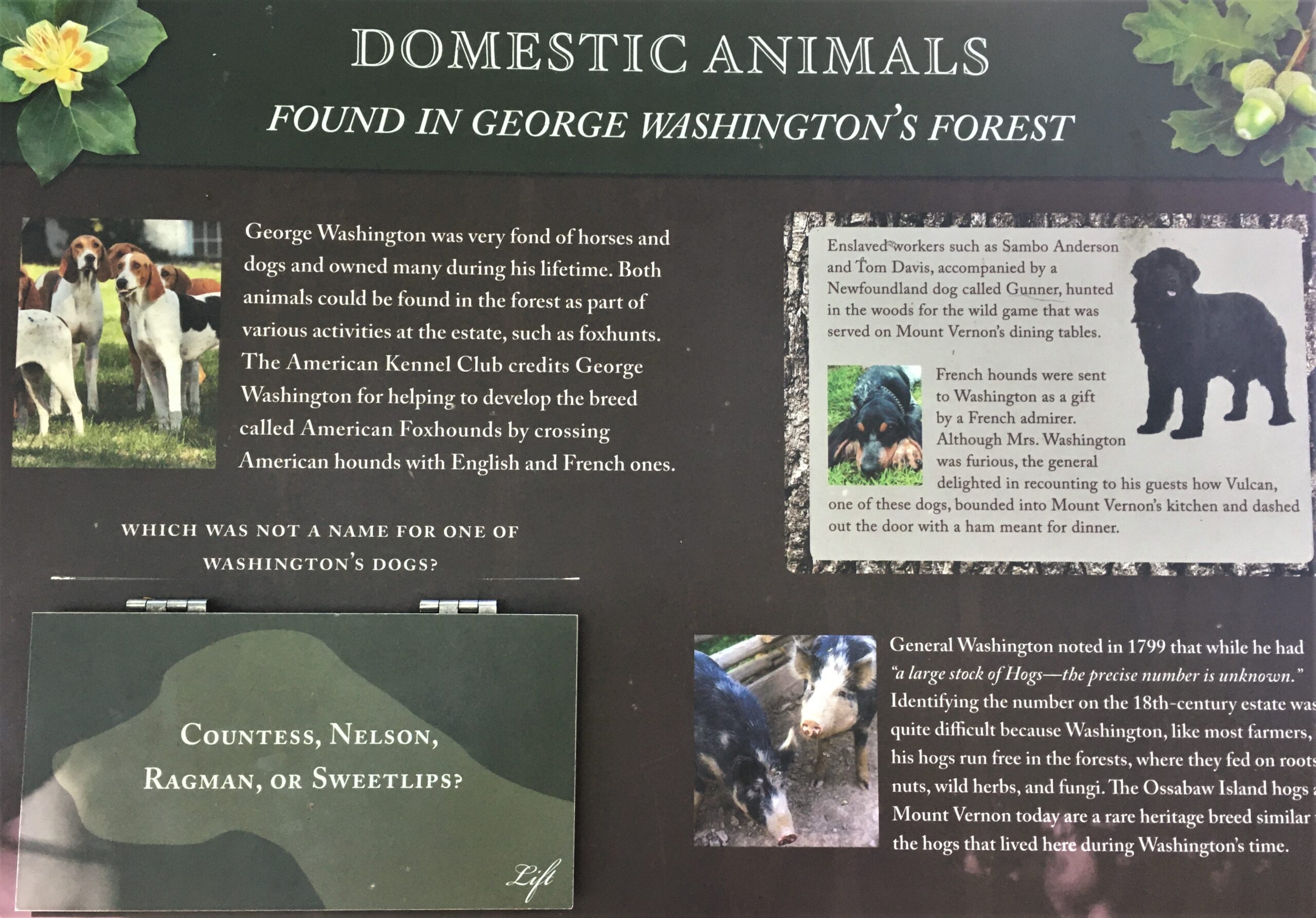

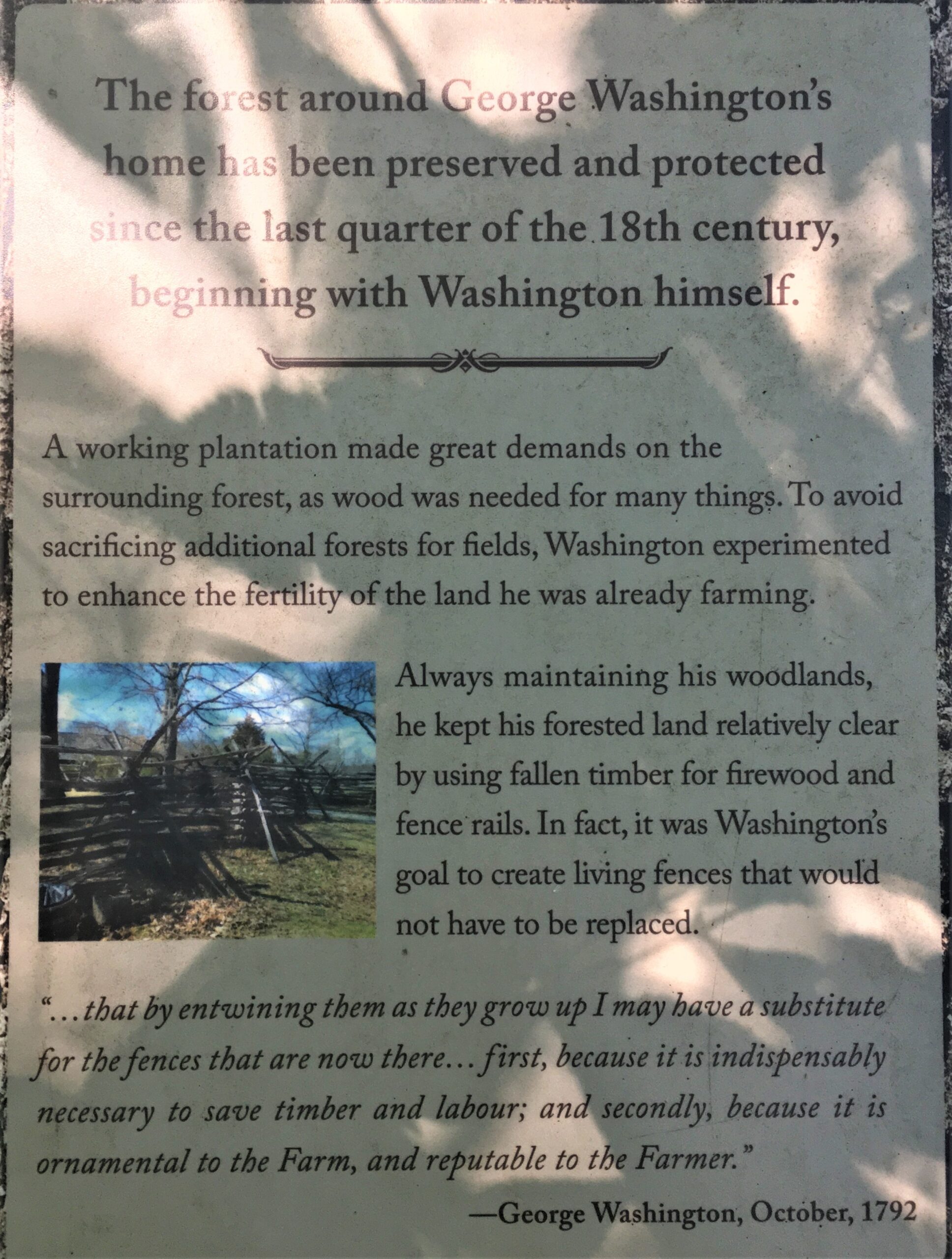

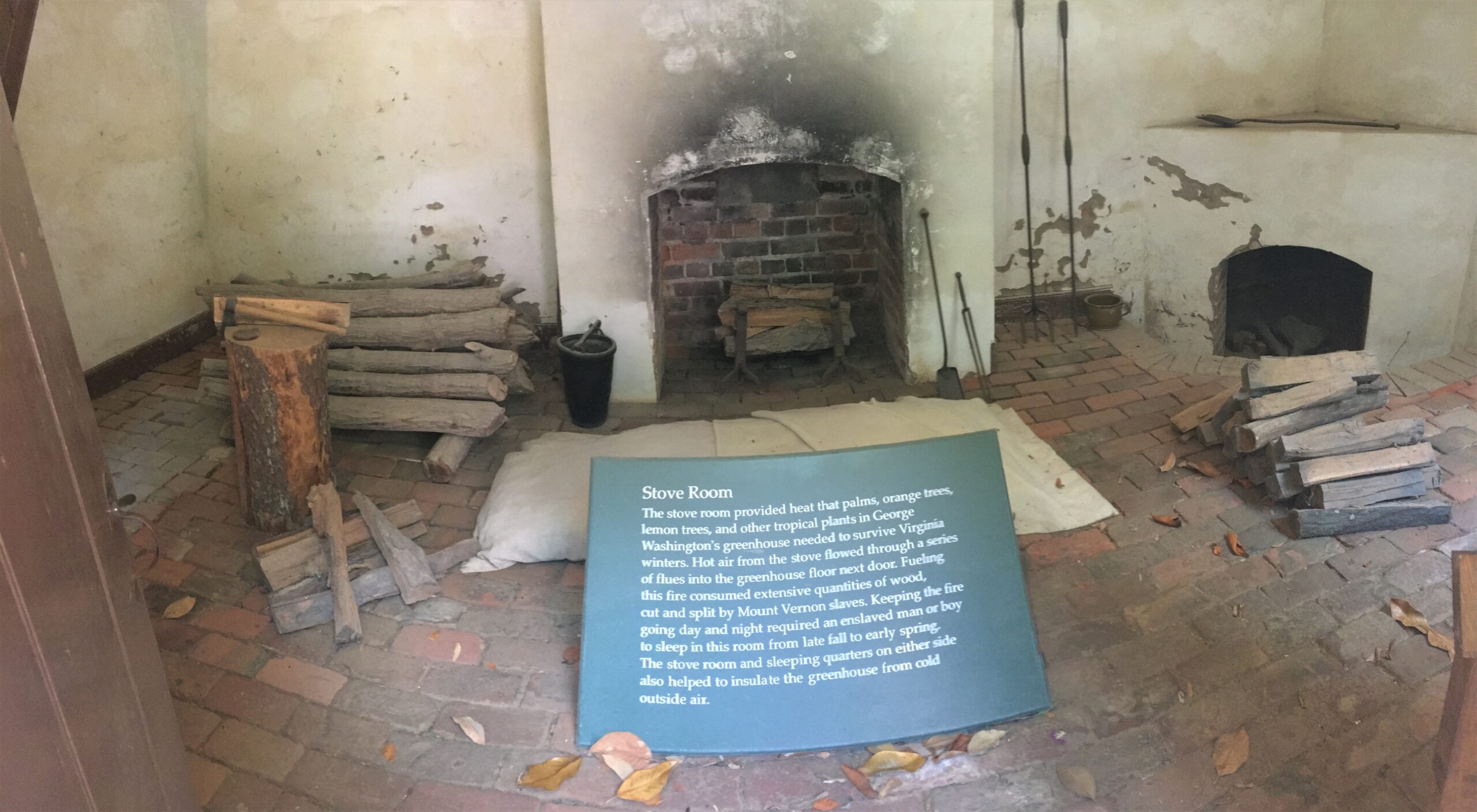

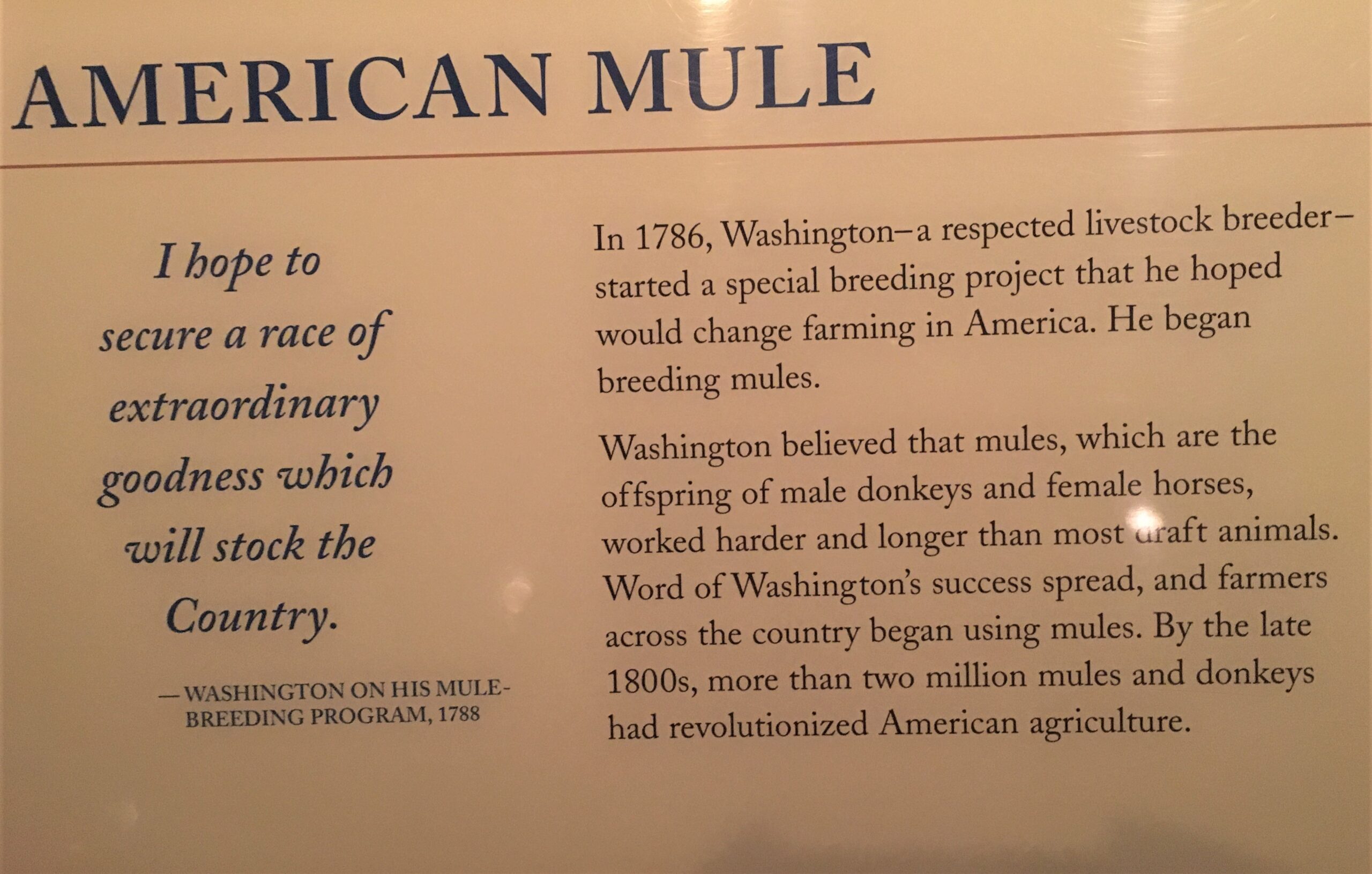

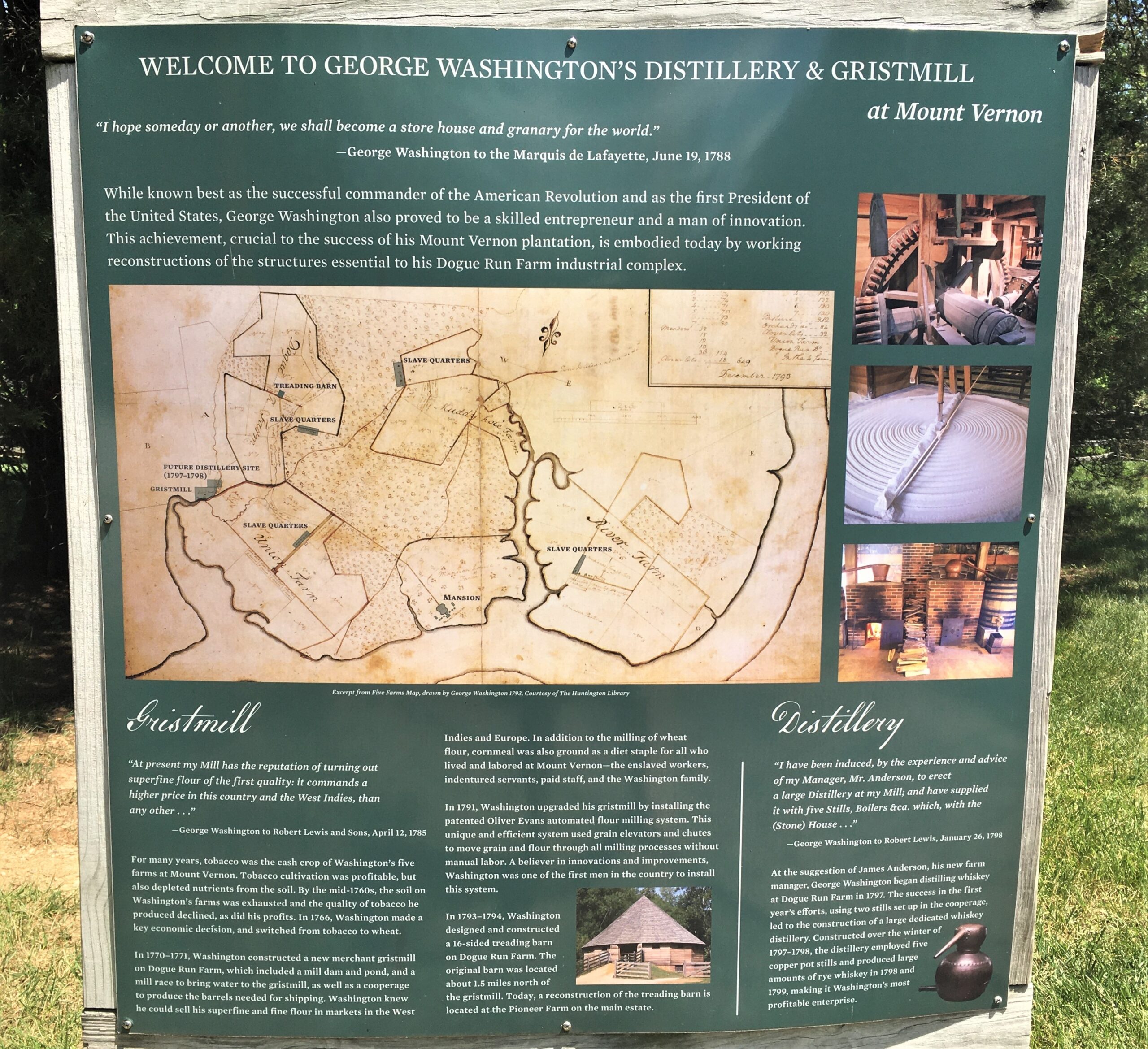

The information we found here was very enlightening, as we learned a bit (more like a LOT) more about George Washington, the man. He was very involved in the farming aspect – with both plants and animals. And he was quite the innovator as well. Plus, he was pretty diversified and involved with his various holdings.

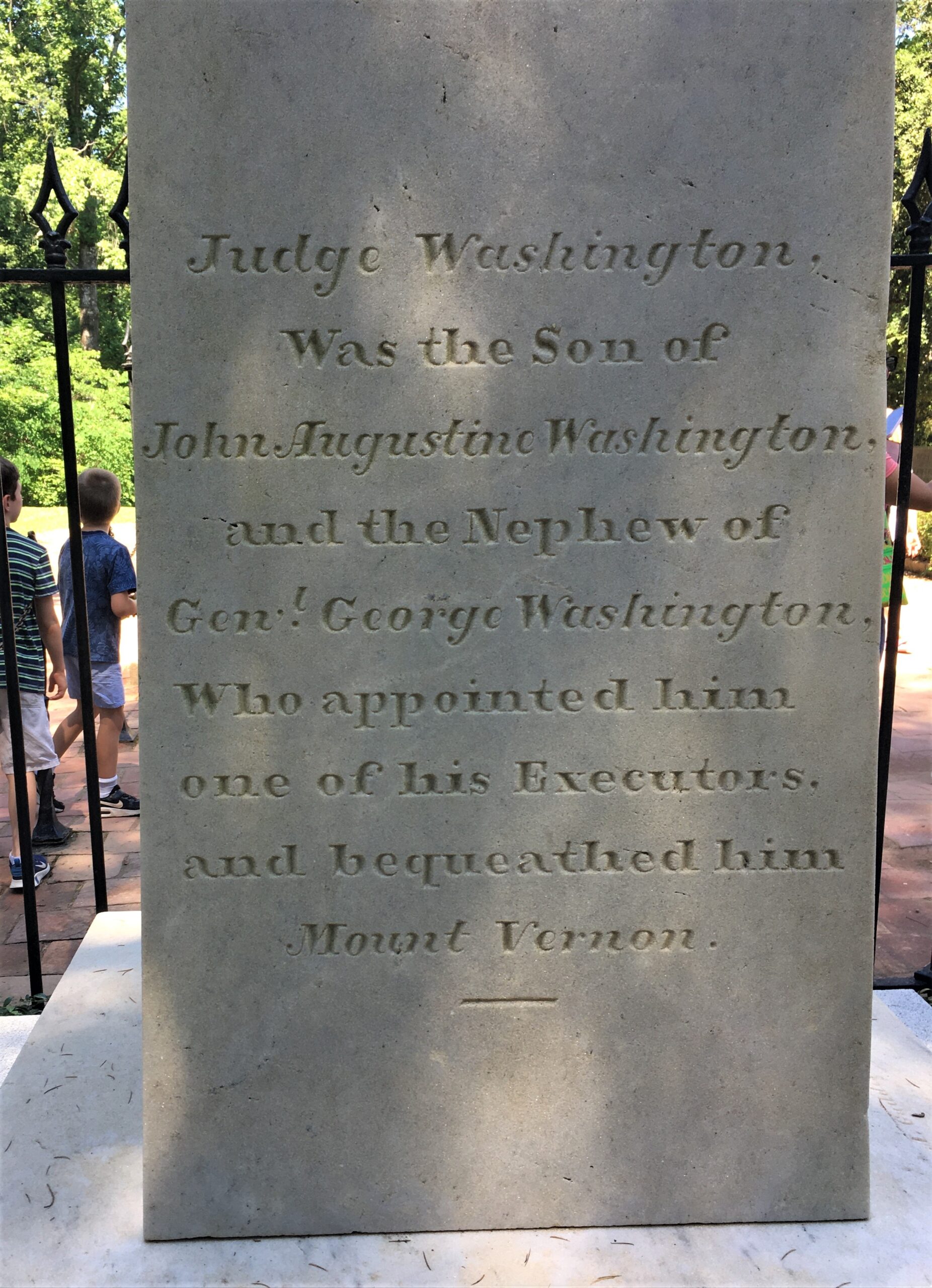

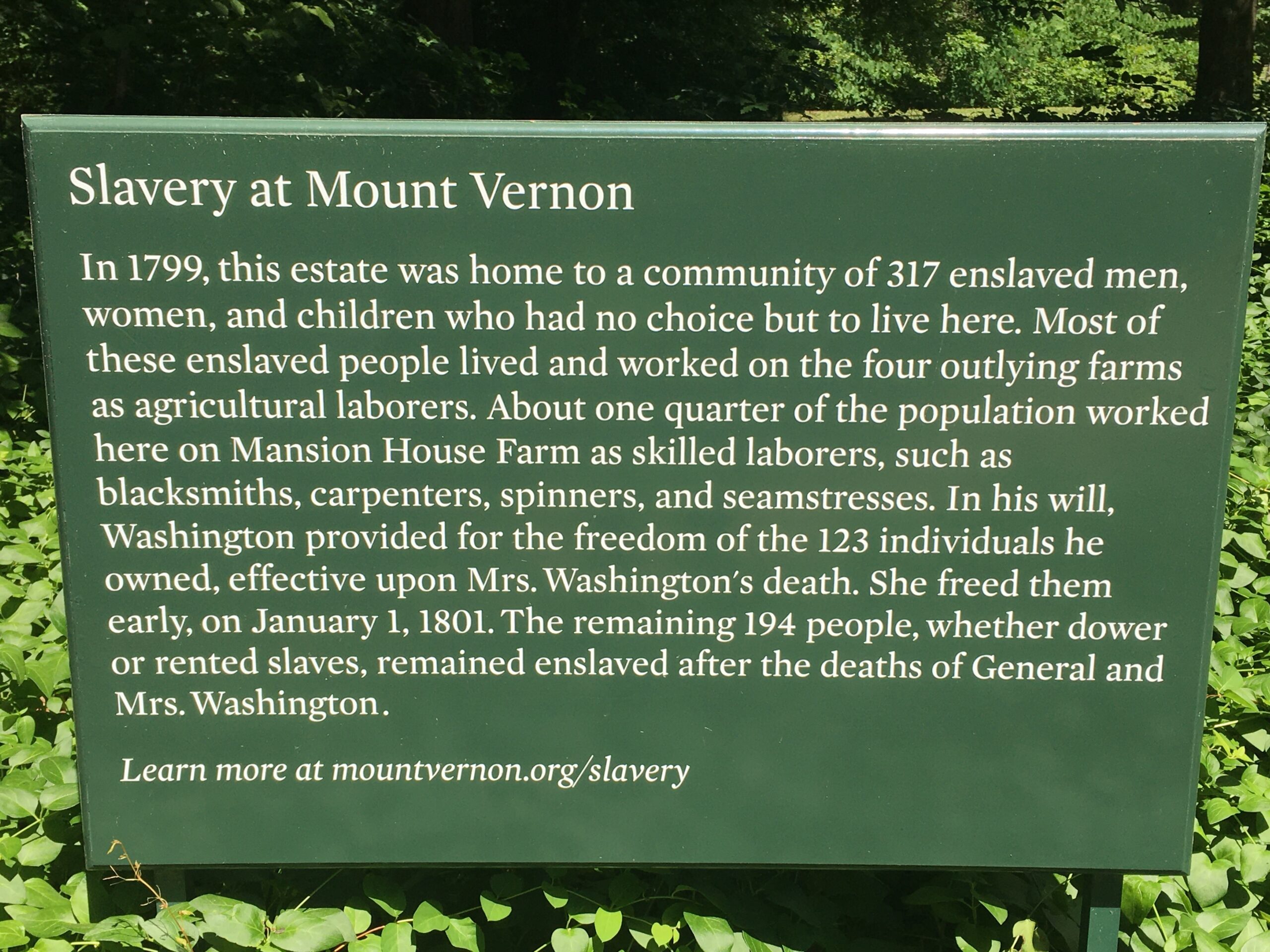

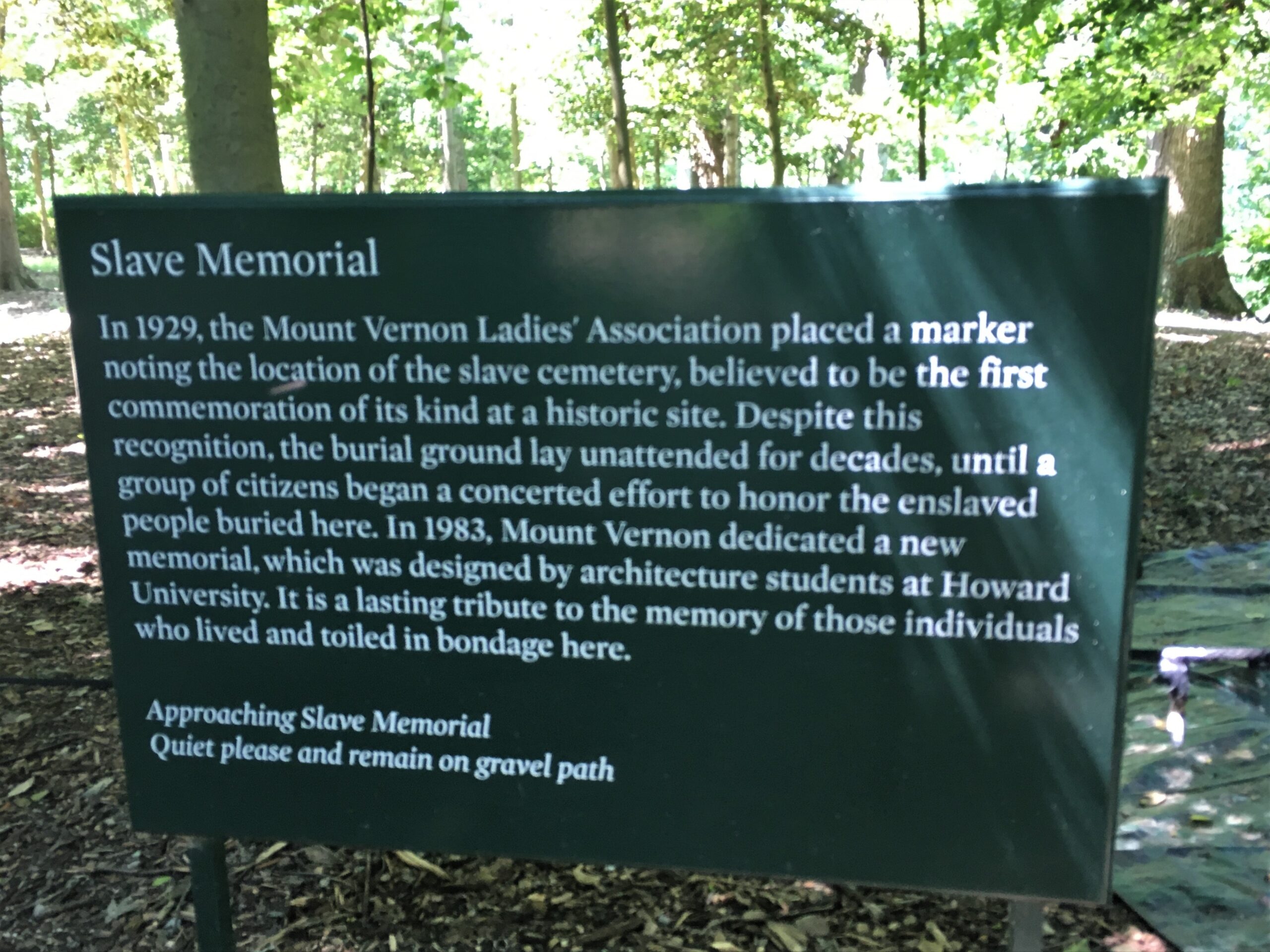

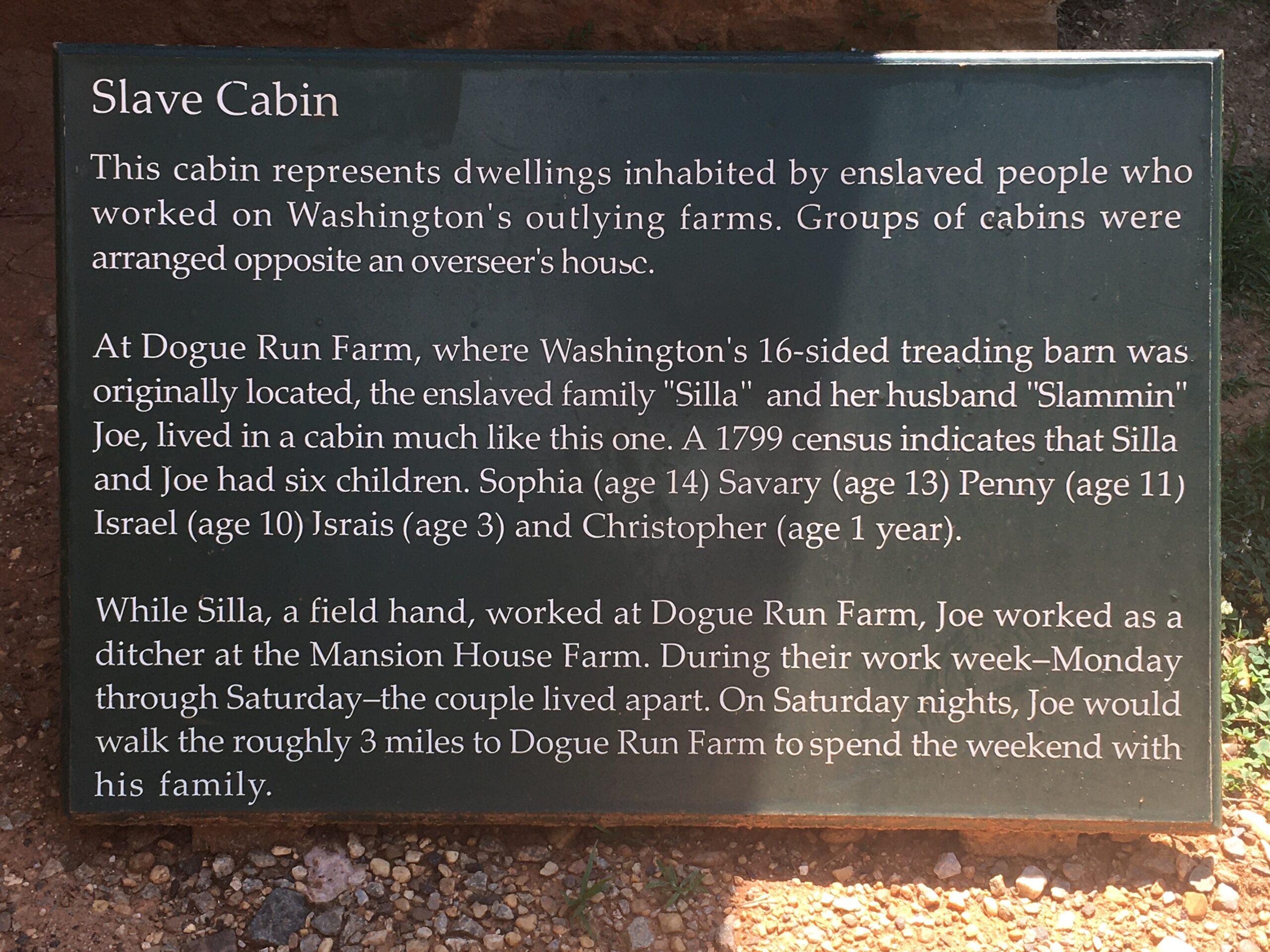

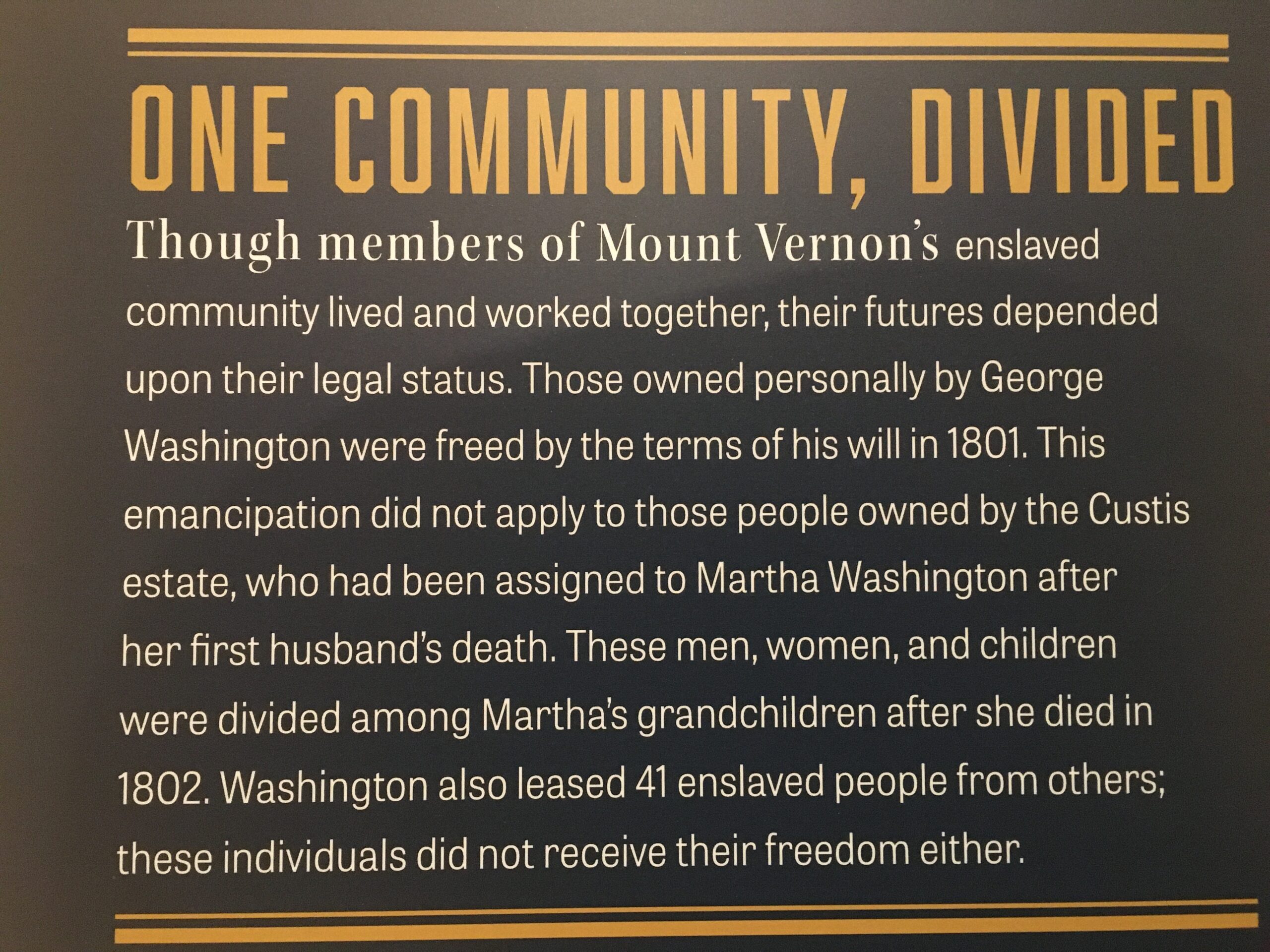

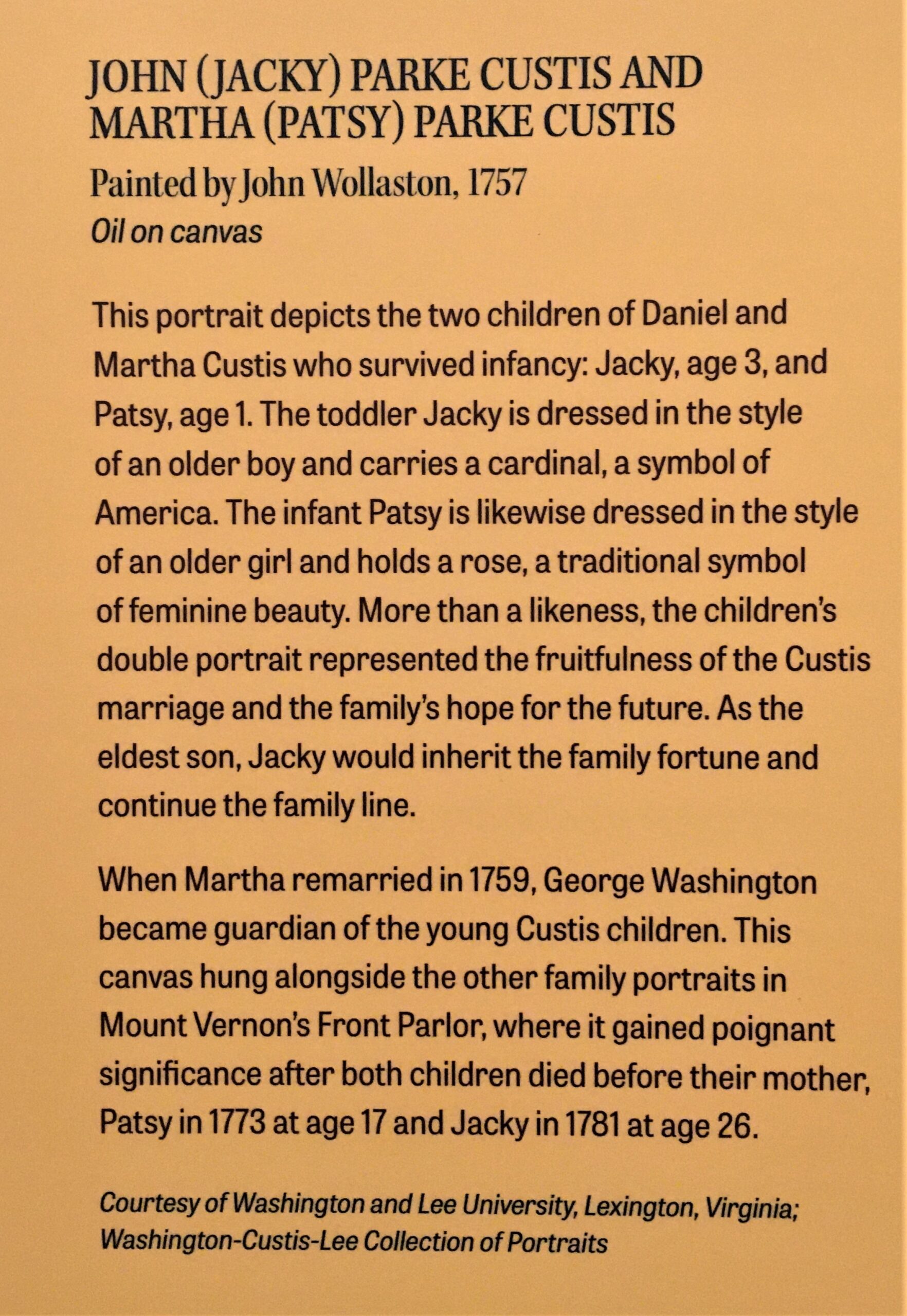

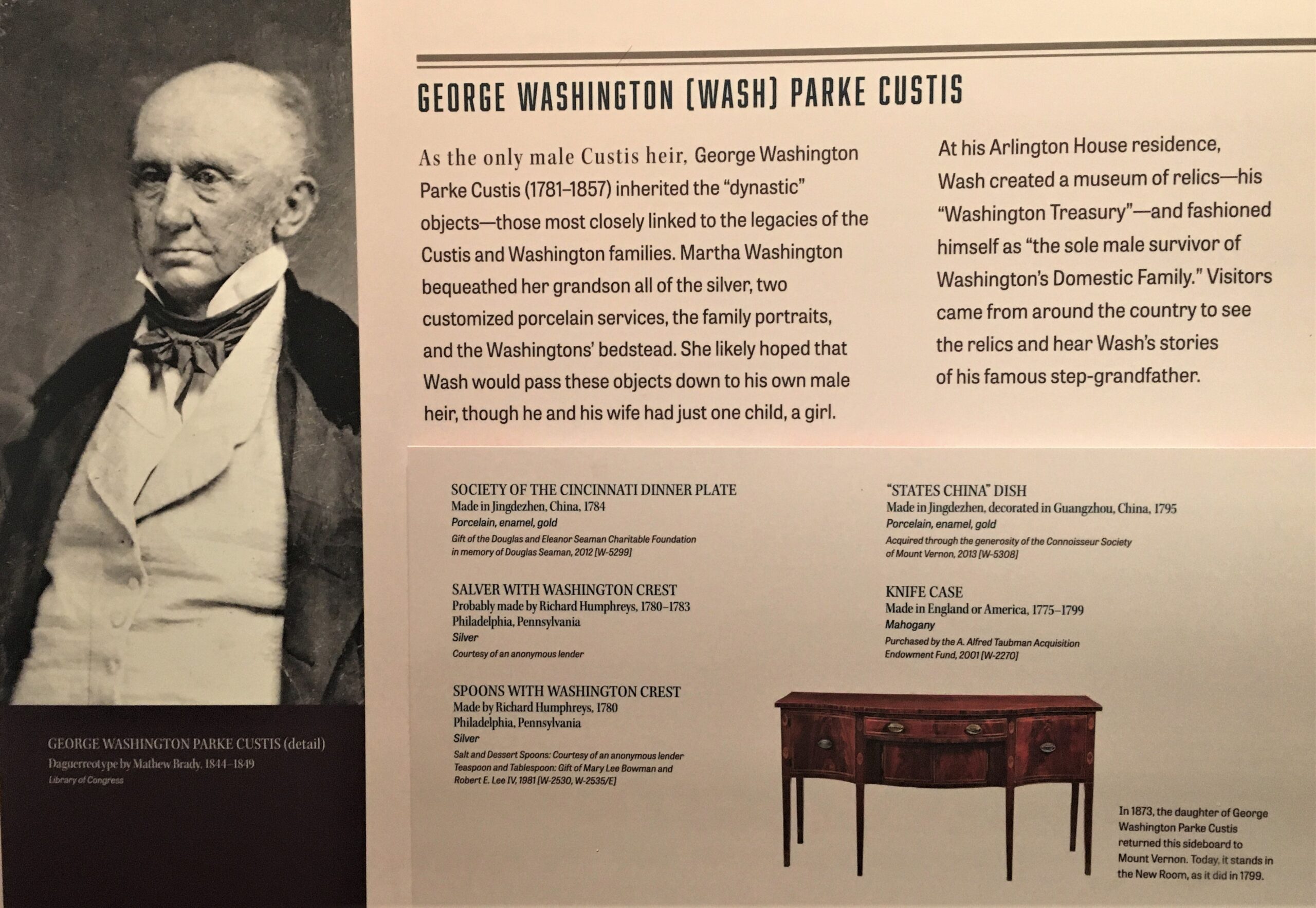

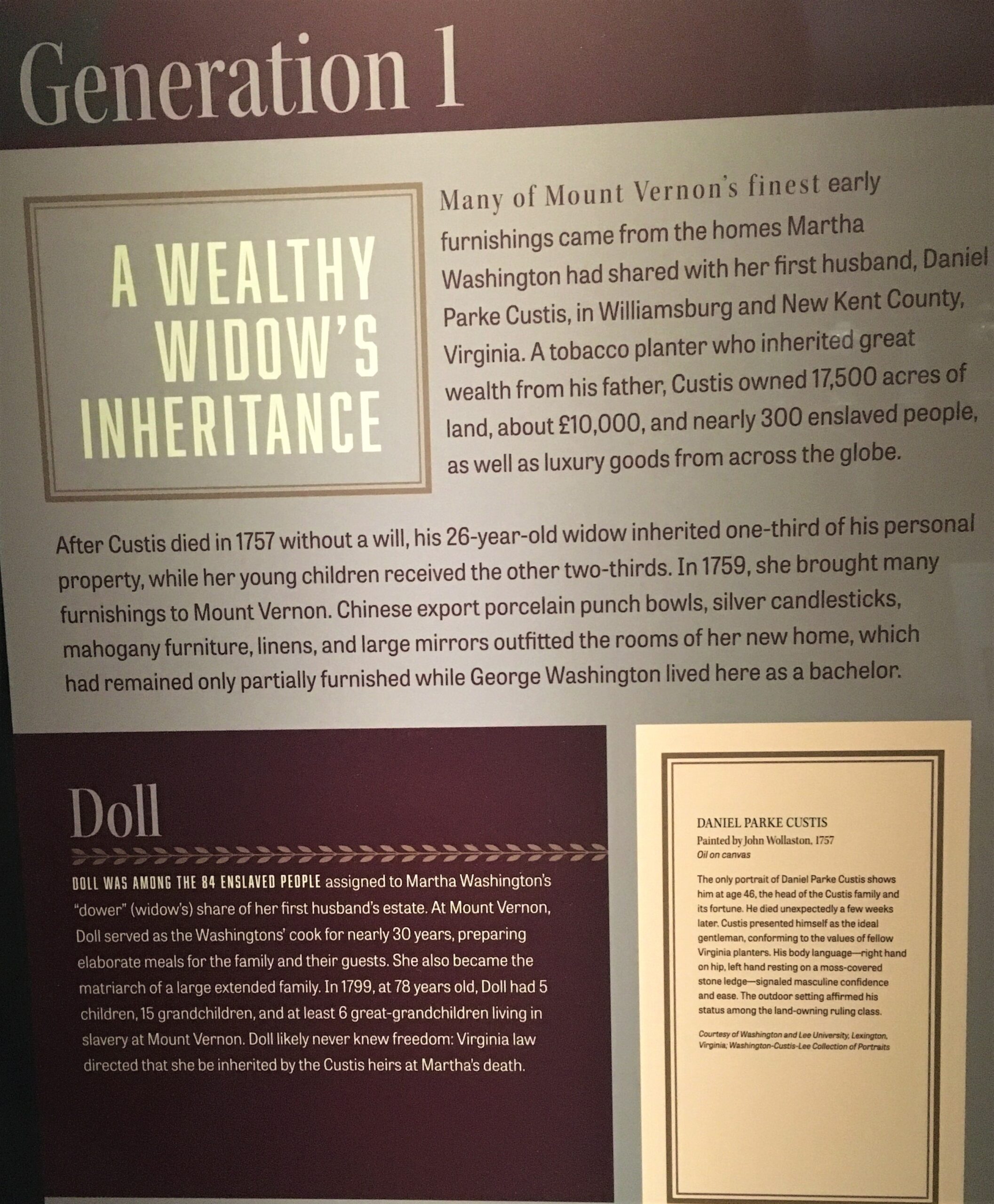

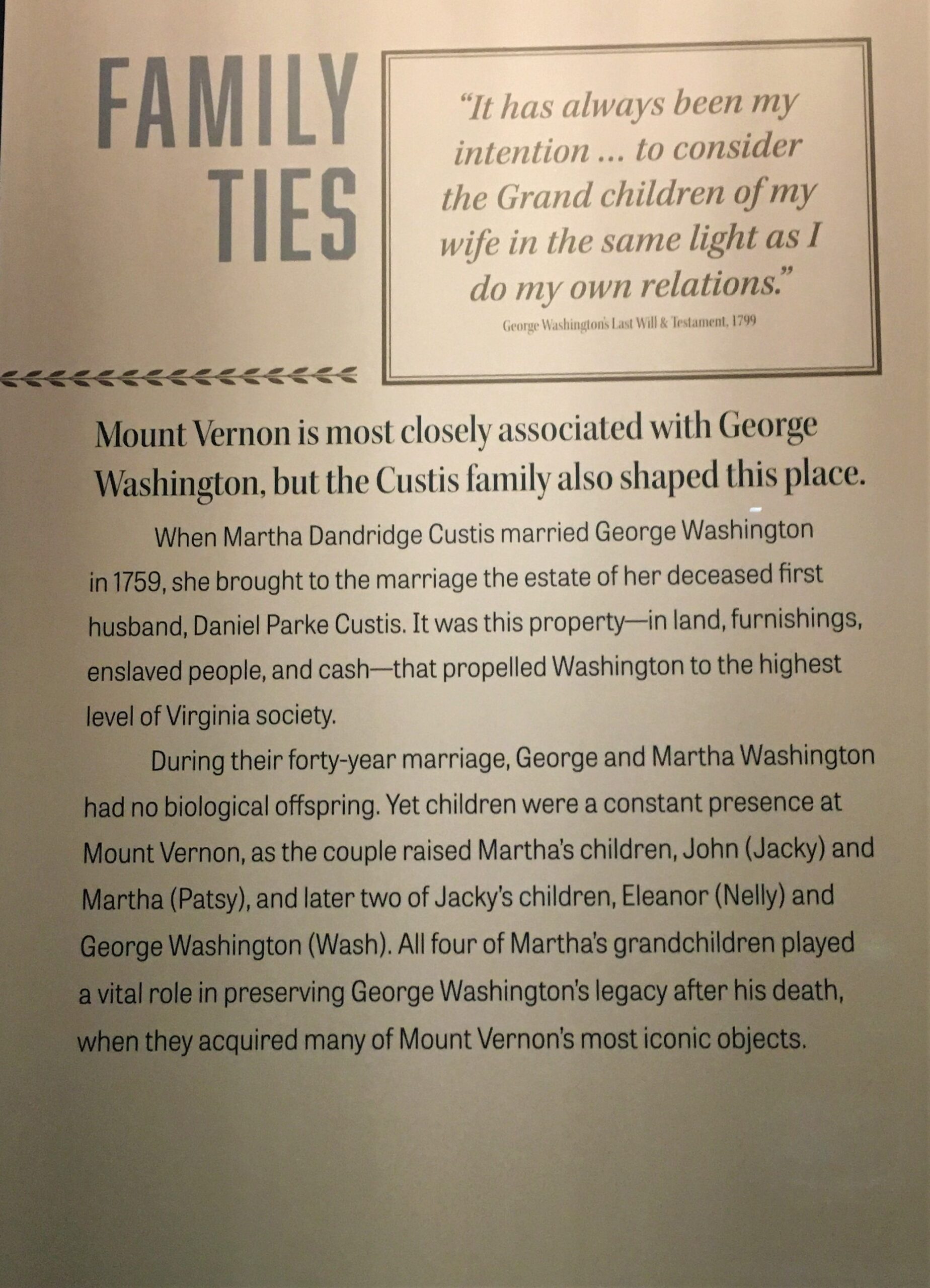

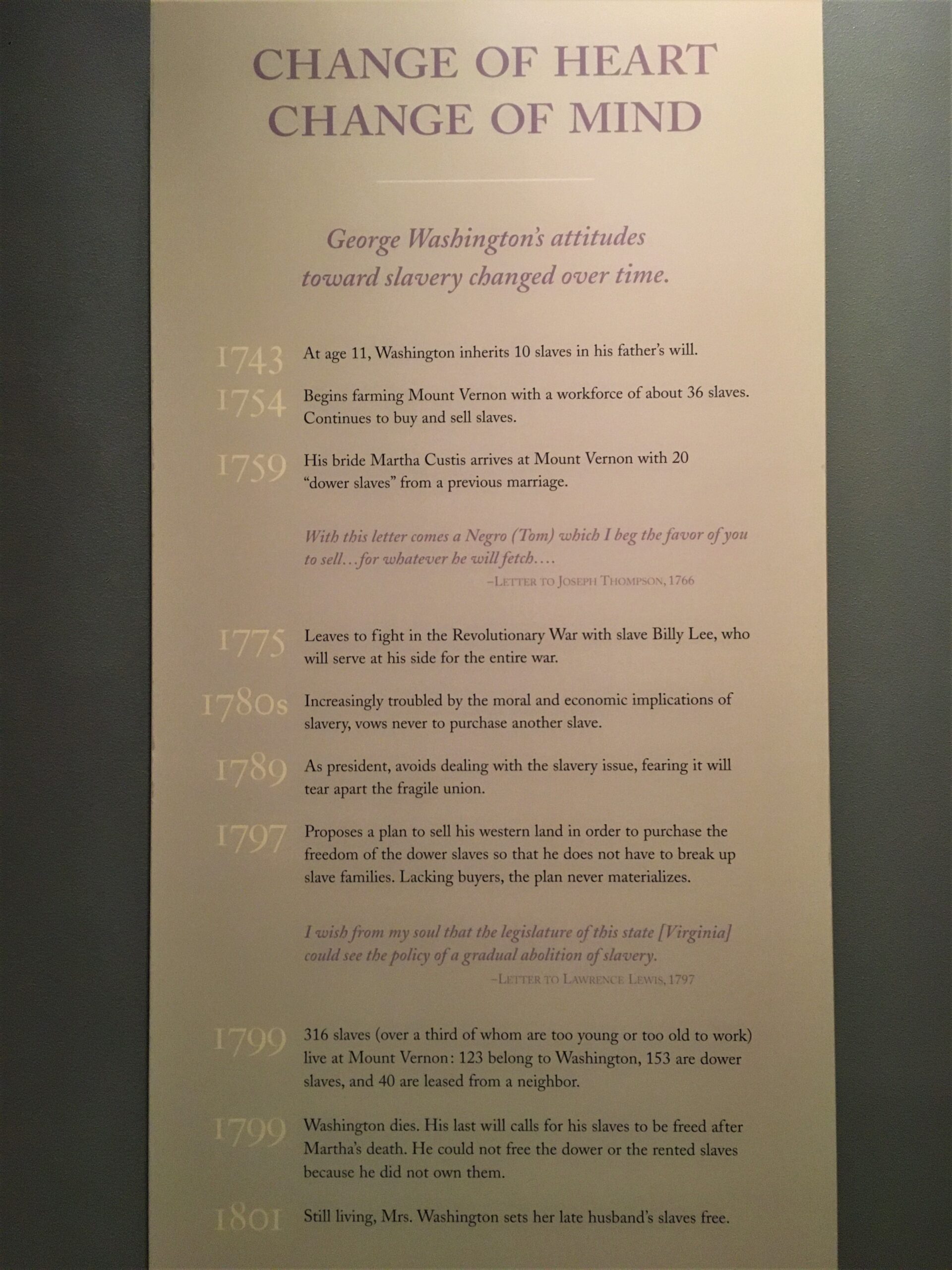

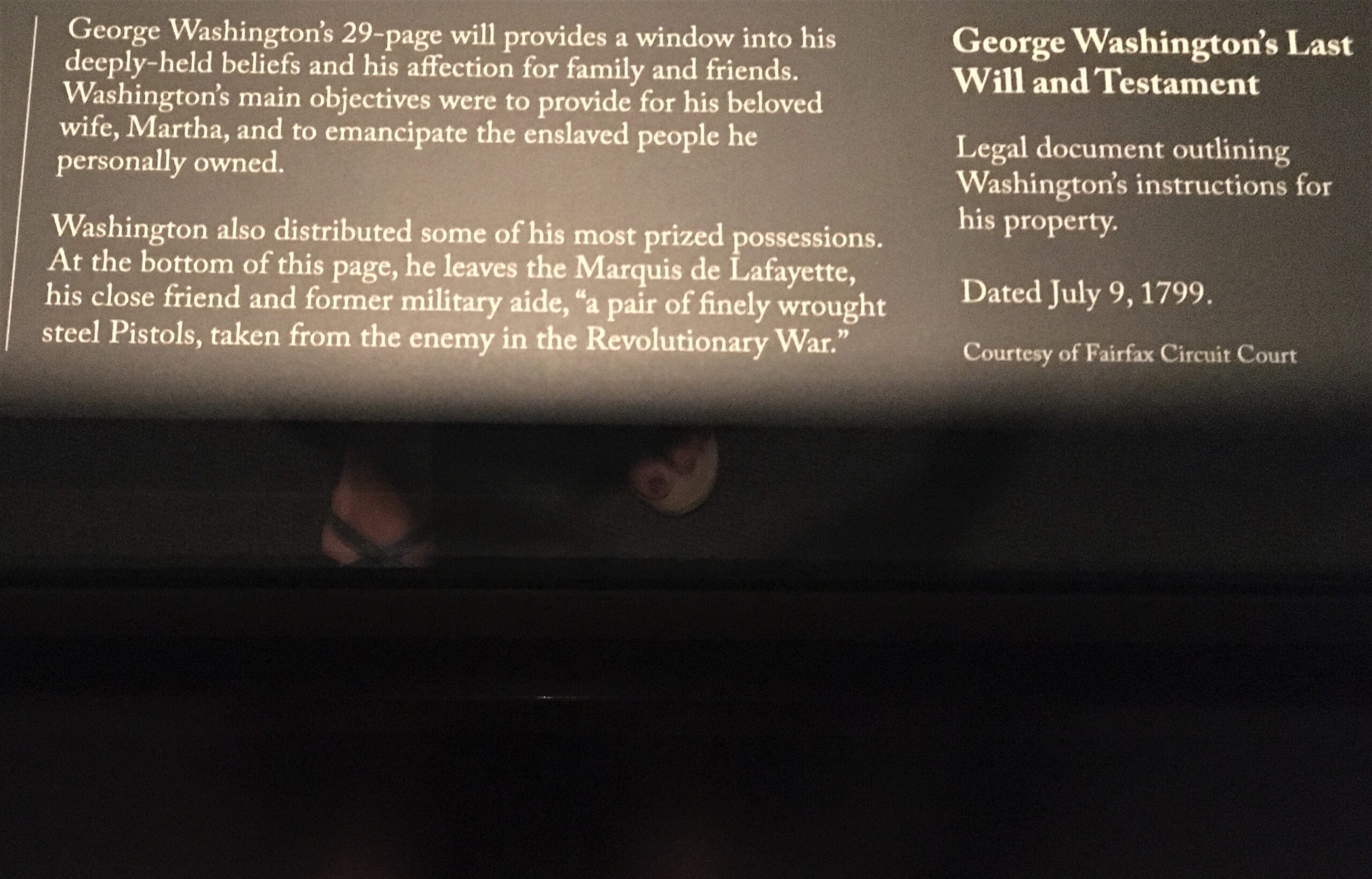

And yes. Our first president owned slaves – 317 at the time of his death in 1799. But he didn’t like enslaving people and wrote of his desire to stop the practice. When he died in 1799, 123 of them belonged to him and were freed upon his death. The rest came from Martha’s deceased husband’s estate and by law had to be returned to the Custis family upon her death in 1802.

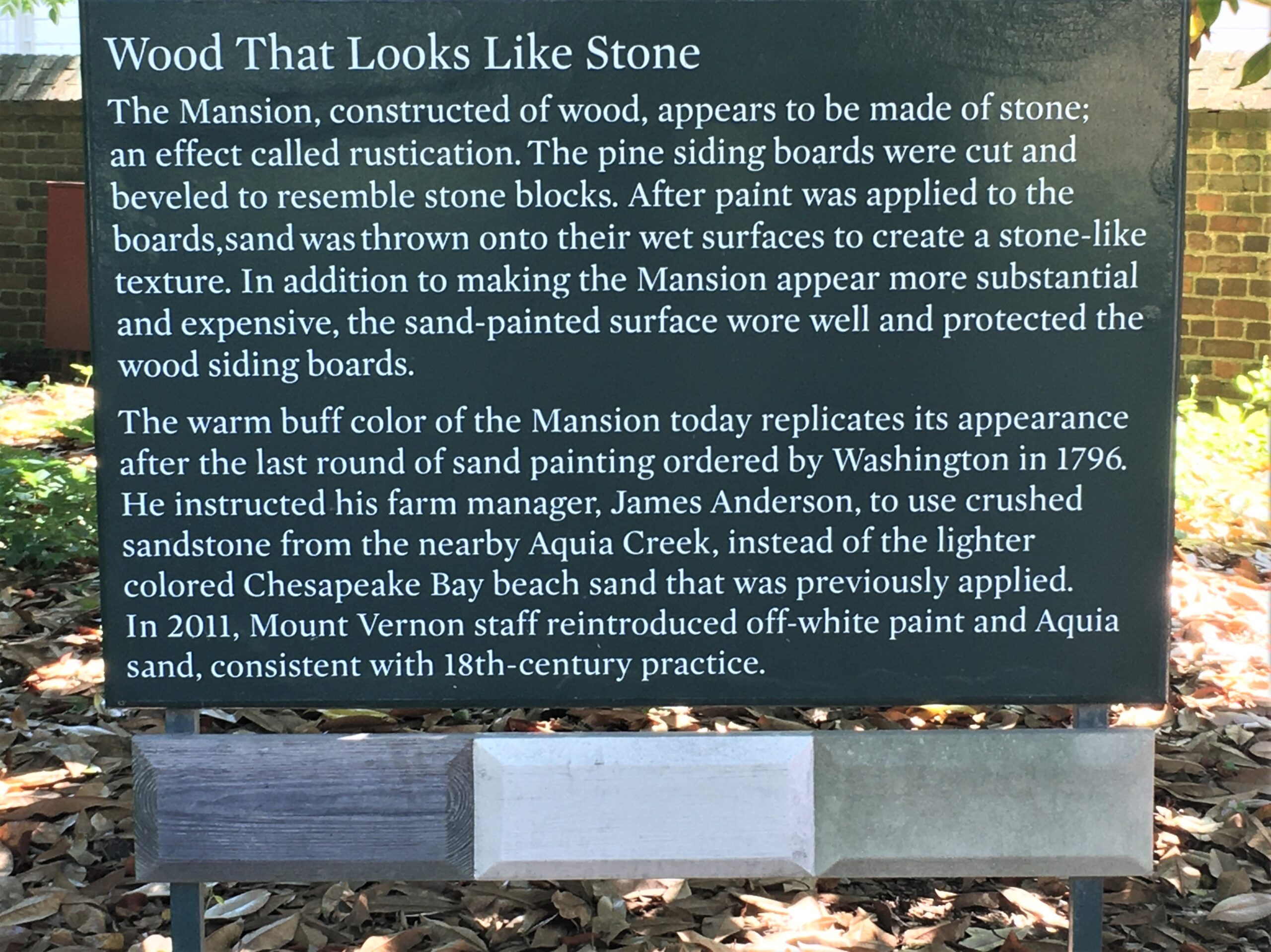

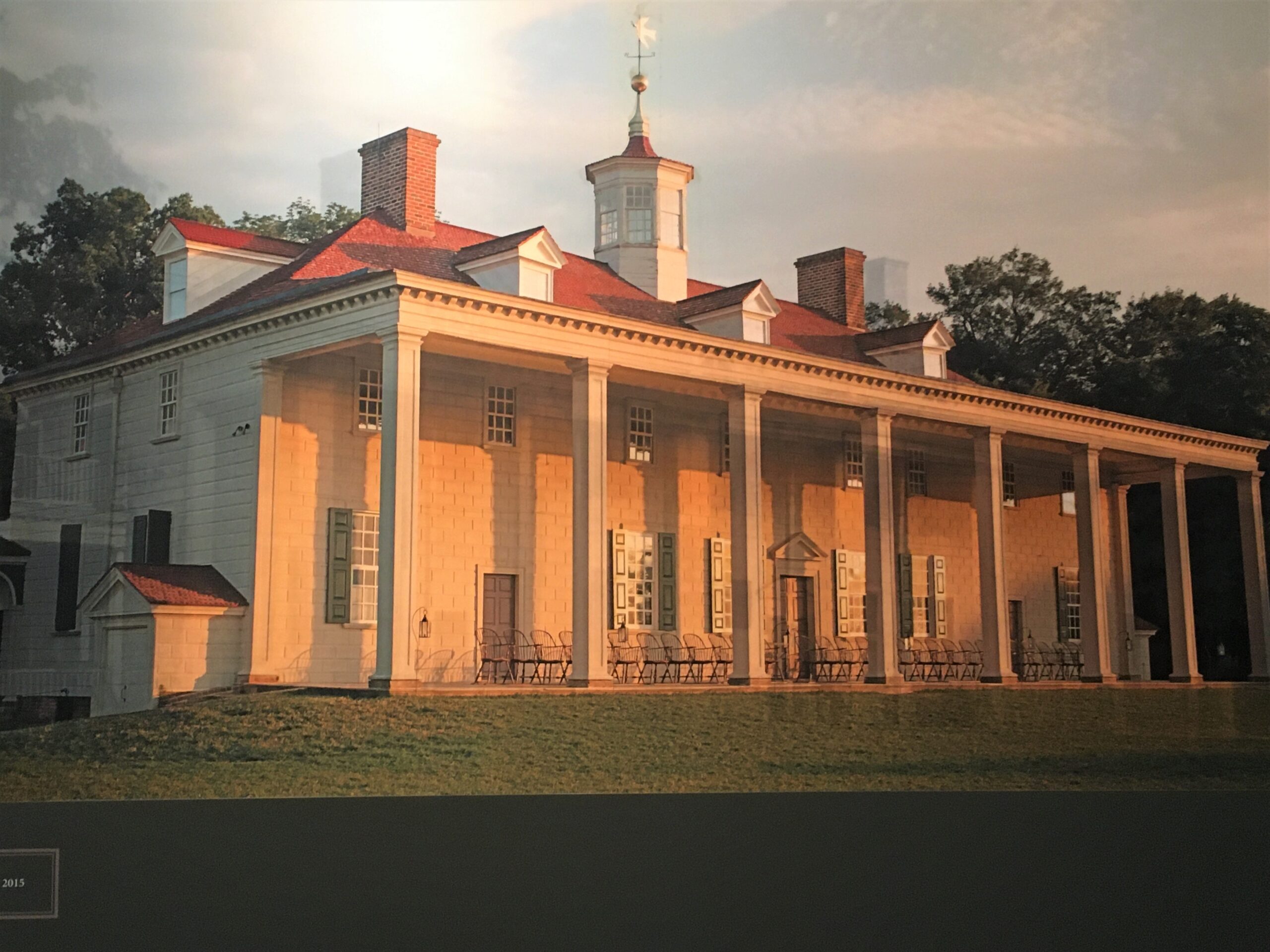

One of the things that surprised us is that the mansion isn’t white. It’s more sand-colored, and for good reason, as you’ll see when you get to the pictures.

You need timed tickets to tour the mansion. When your time comes, you get in line where they send through about twenty bodies at a time. This goes on all day, nearly every day. And yet, the place looks like George and Martha could come around the corner at any time. They post docents at each area who take over managing the groups, sharing information, and answering questions. I don’t know if these people are on staff or volunteers, but they all seemed knowledgeable and were all very congenial.

There are all kinds of paths around the estate to explore, and a large (air conditioned!) museum, and when you finish here, there’s also his distillery, which is off the premises. Unfortunately, it’s temporarily closed, but that didn’t stop us from visiting. 😊

Enjoy the tour! But better yet, come see it for yourselves!

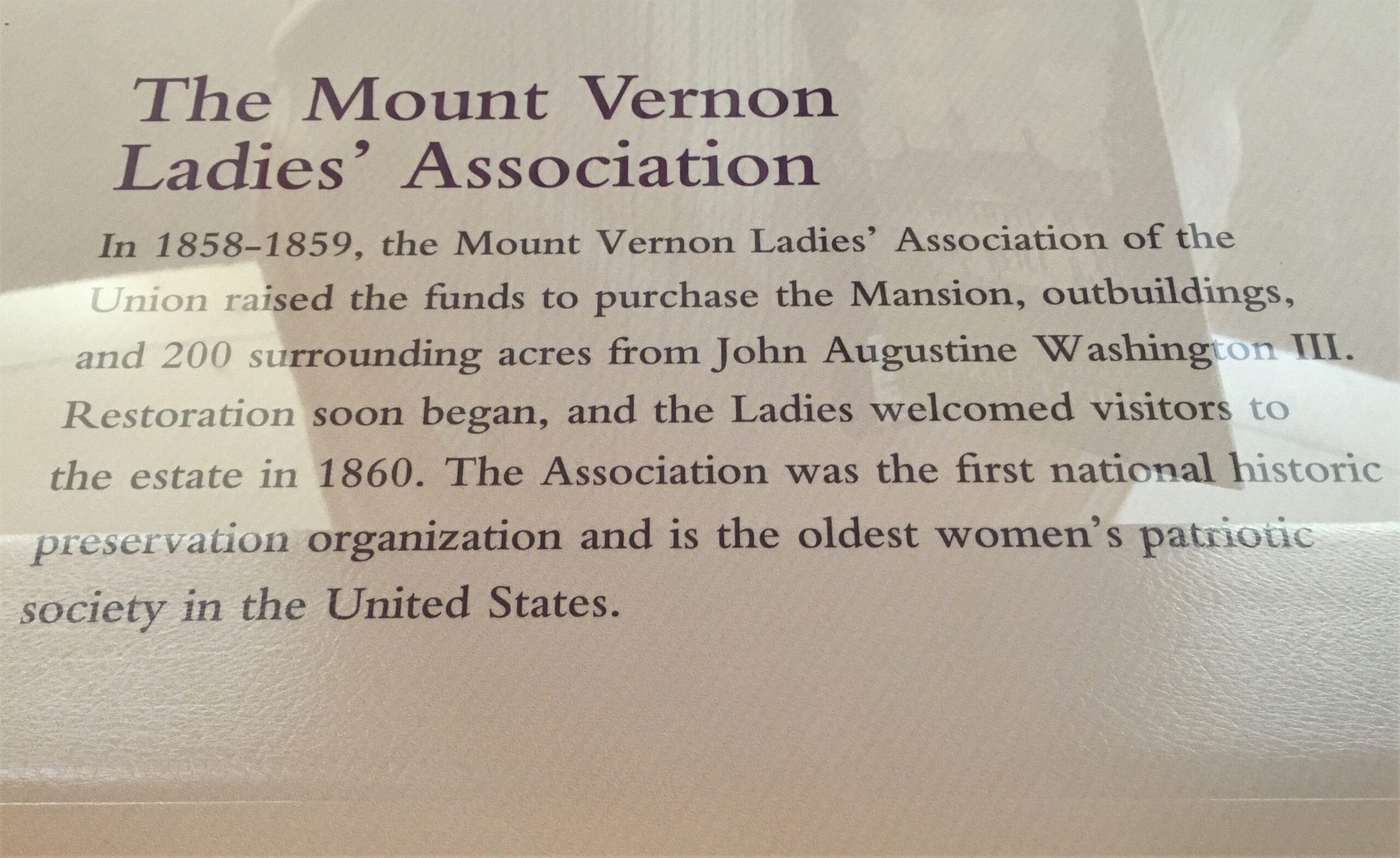

All expenses are covered solely from ticket sales, concessions, the gift shop and donations.

You’ll read more about them if you read the Mount Vernon Special Edition.

This revelation was fascinating!

Taken later in the day because they have things roped off along the front.

So called because that’s what George and Martha called it – – because it was new. : )

There’s a lot of renovation going on to the outside.

They moved the chairs that normally line the porch, out onto the lawn.

I understand that, but this is really green!

They have that here, but you can’t get a picture because you can’t get a good angle.

Wanna guess what that contraption is that’s hovering over the chair?

It’s a fan! Operated by the foot pedals under the desk!

Repairs and archeology going on out back.

Too bad we can’t get a good picture.

But if you want to see it, I’m certain there are plenty of excellent pictures on-line. : )

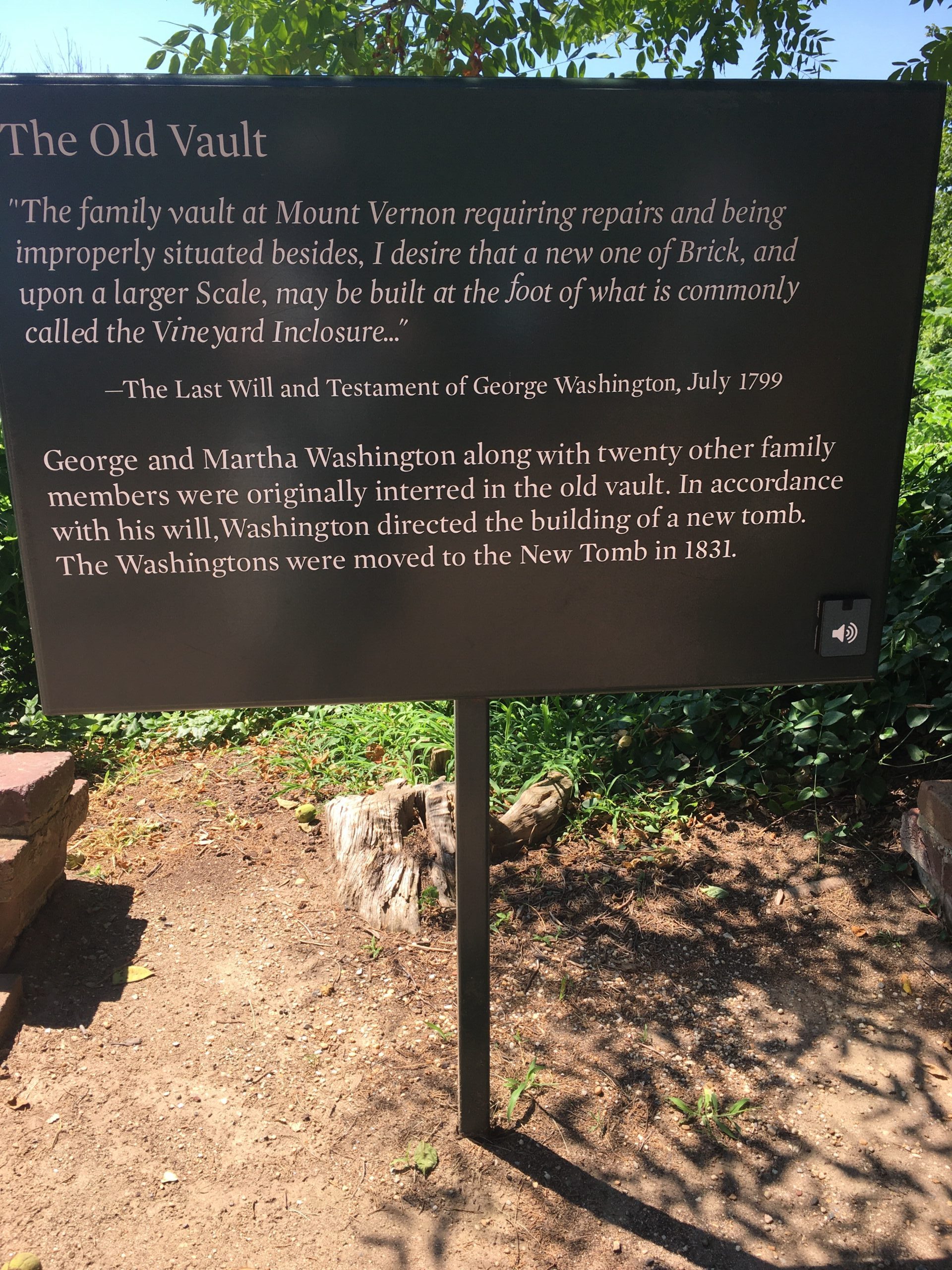

Since no one followed George’s wishes to build a new crypt,

tourists were stealing souvenirs, if you can believe it!

It’s a large vault with 25 additional family members also interred inside.

There’s also one at George and Martha’s vault. We missed both. : (

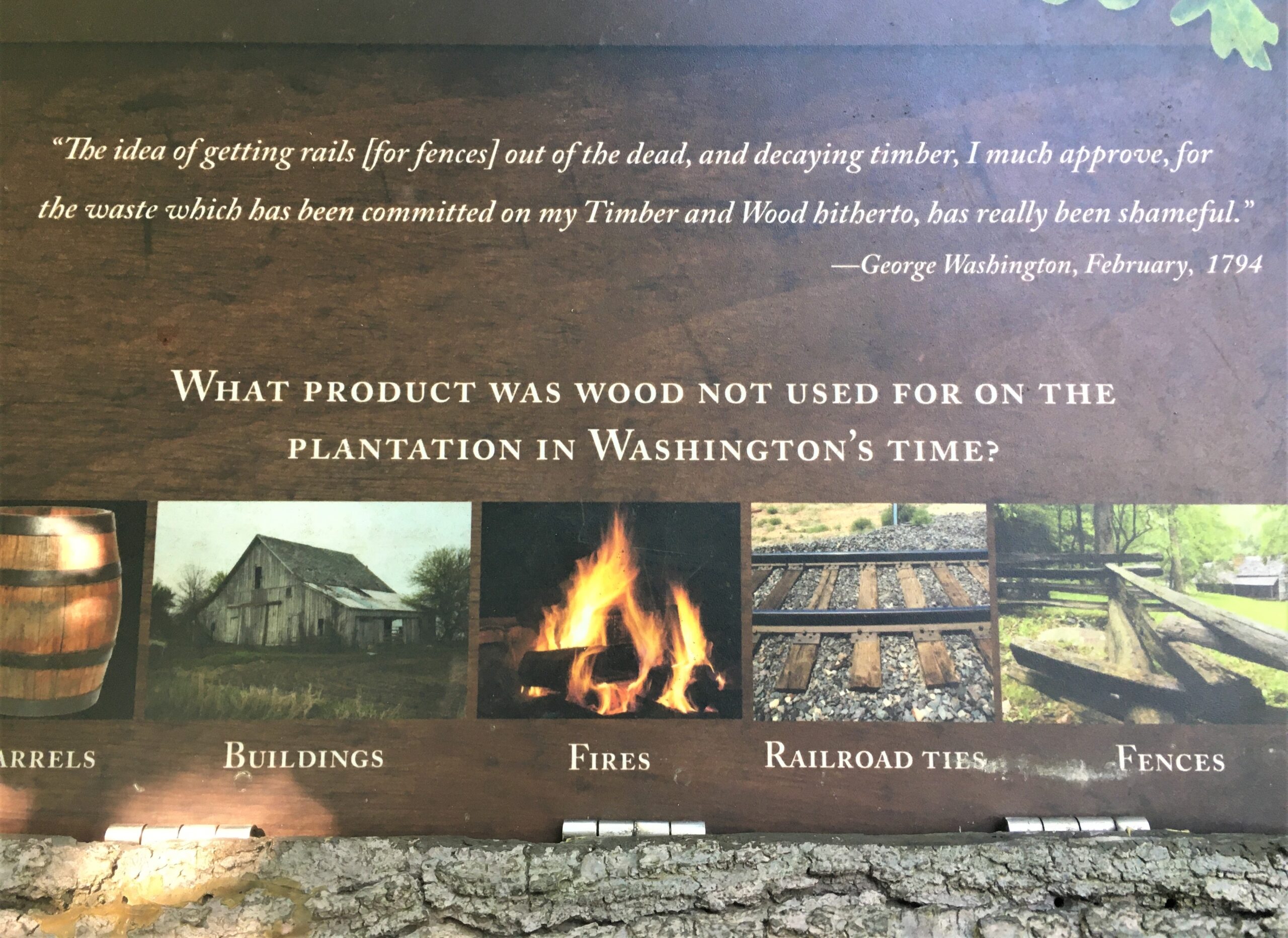

It’s the railroad ties. No trains on the plantation.

There is soooo much information in here!

See what you think . . .

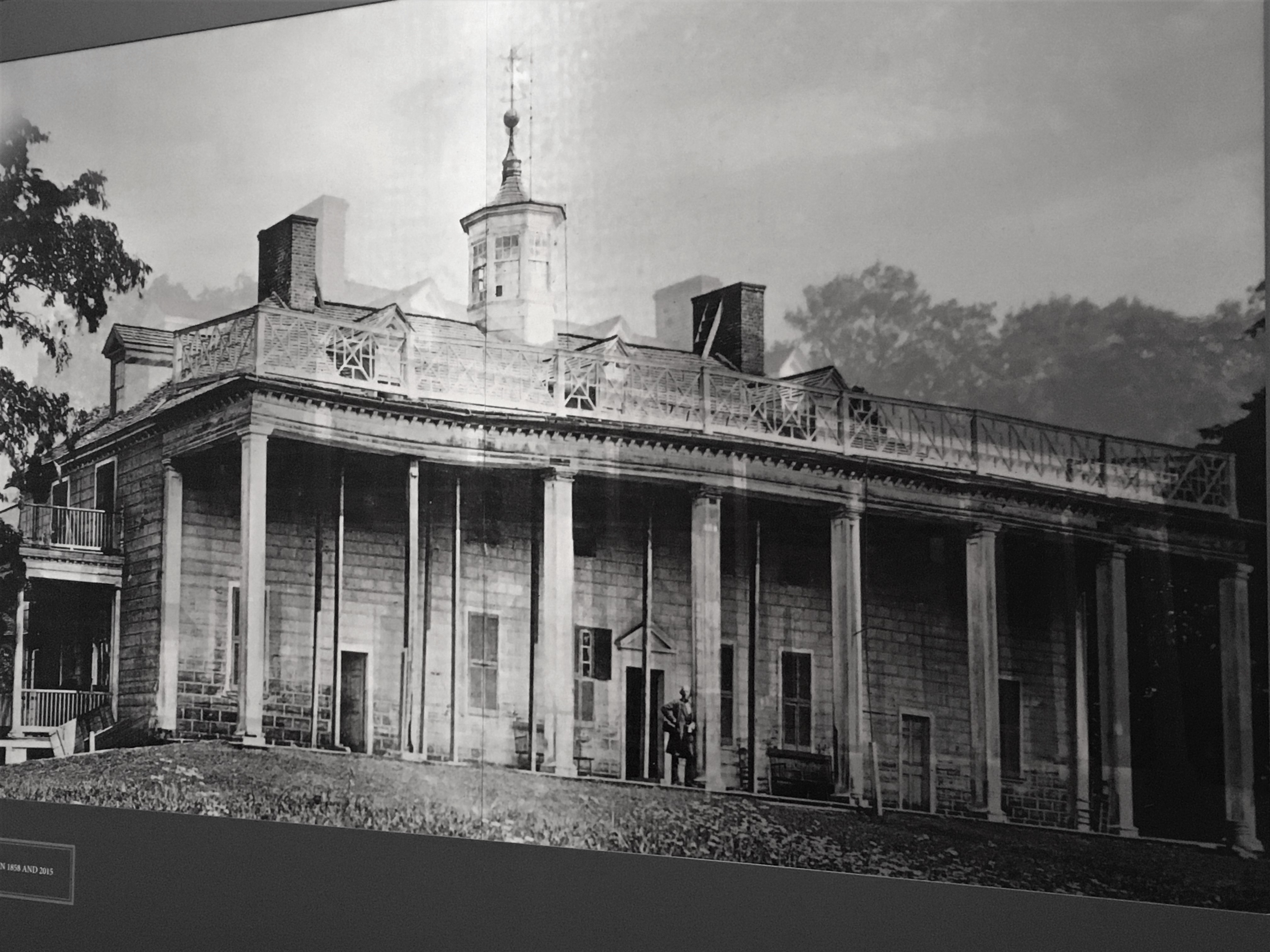

When you walked one way, you saw the mansion as it appeared in 1860 . . .

The shadows you see on both pictures are the remnants of the other picture.

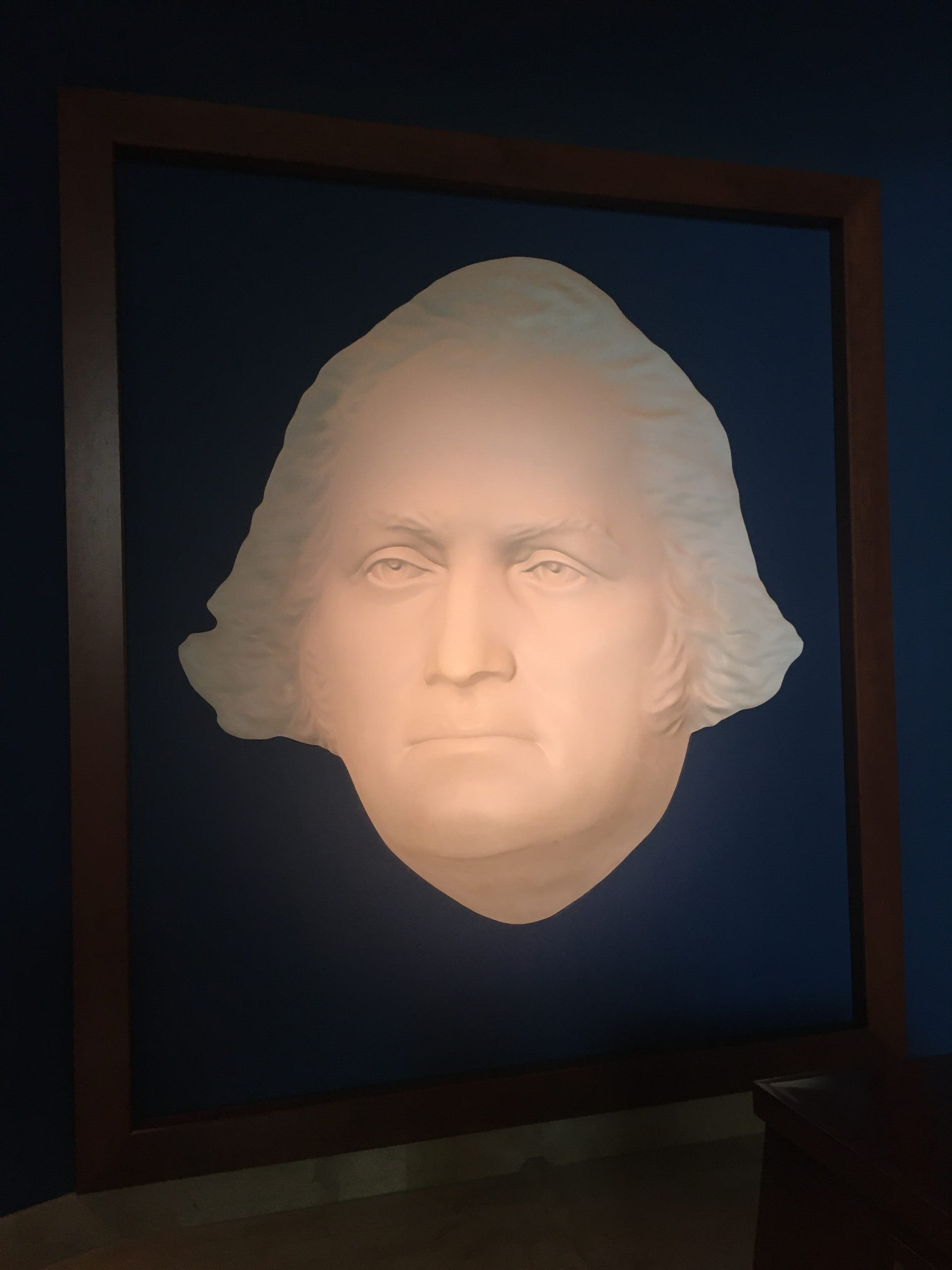

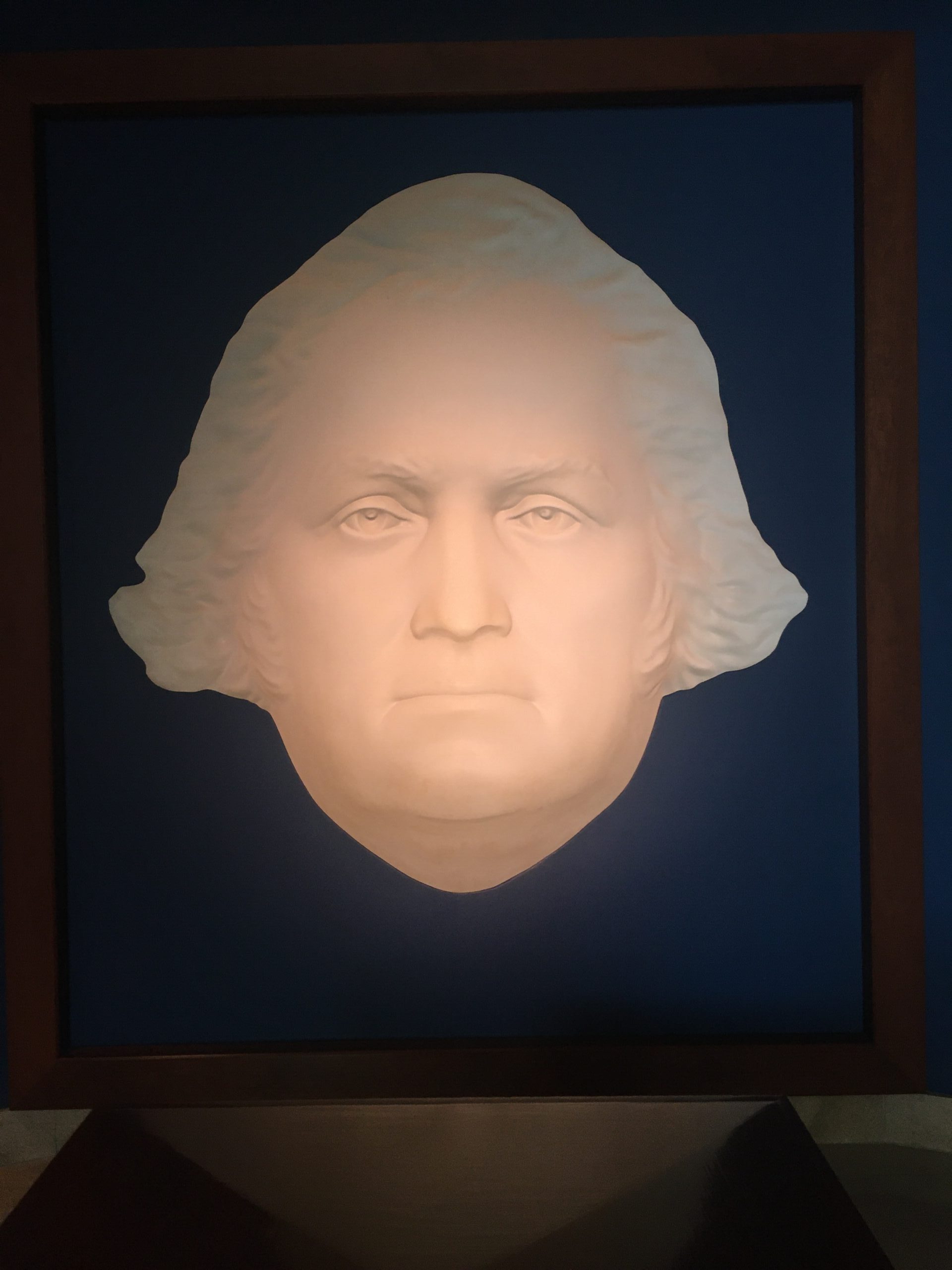

It’s one of those concaved sculptures that follows you wherever you go!

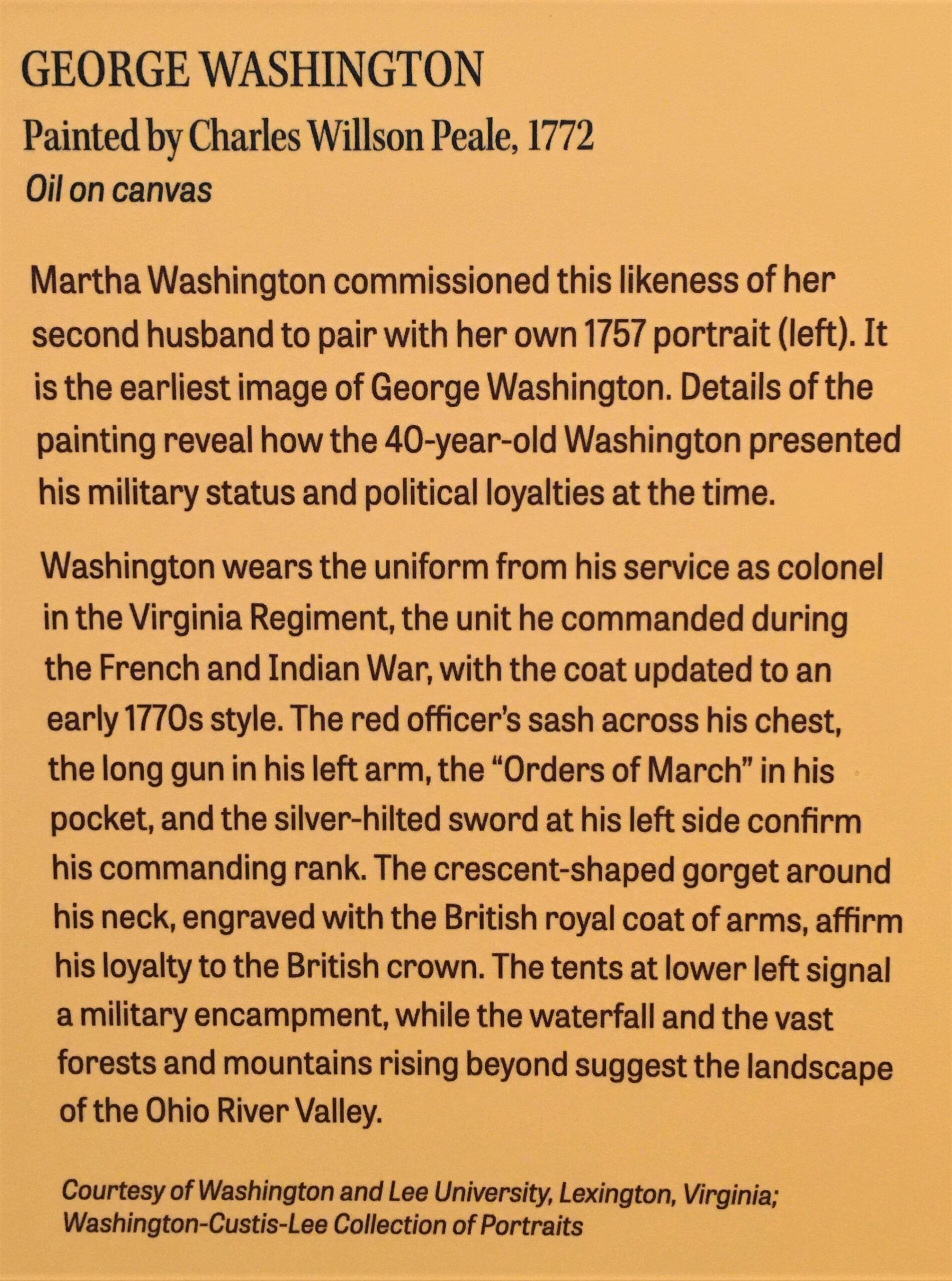

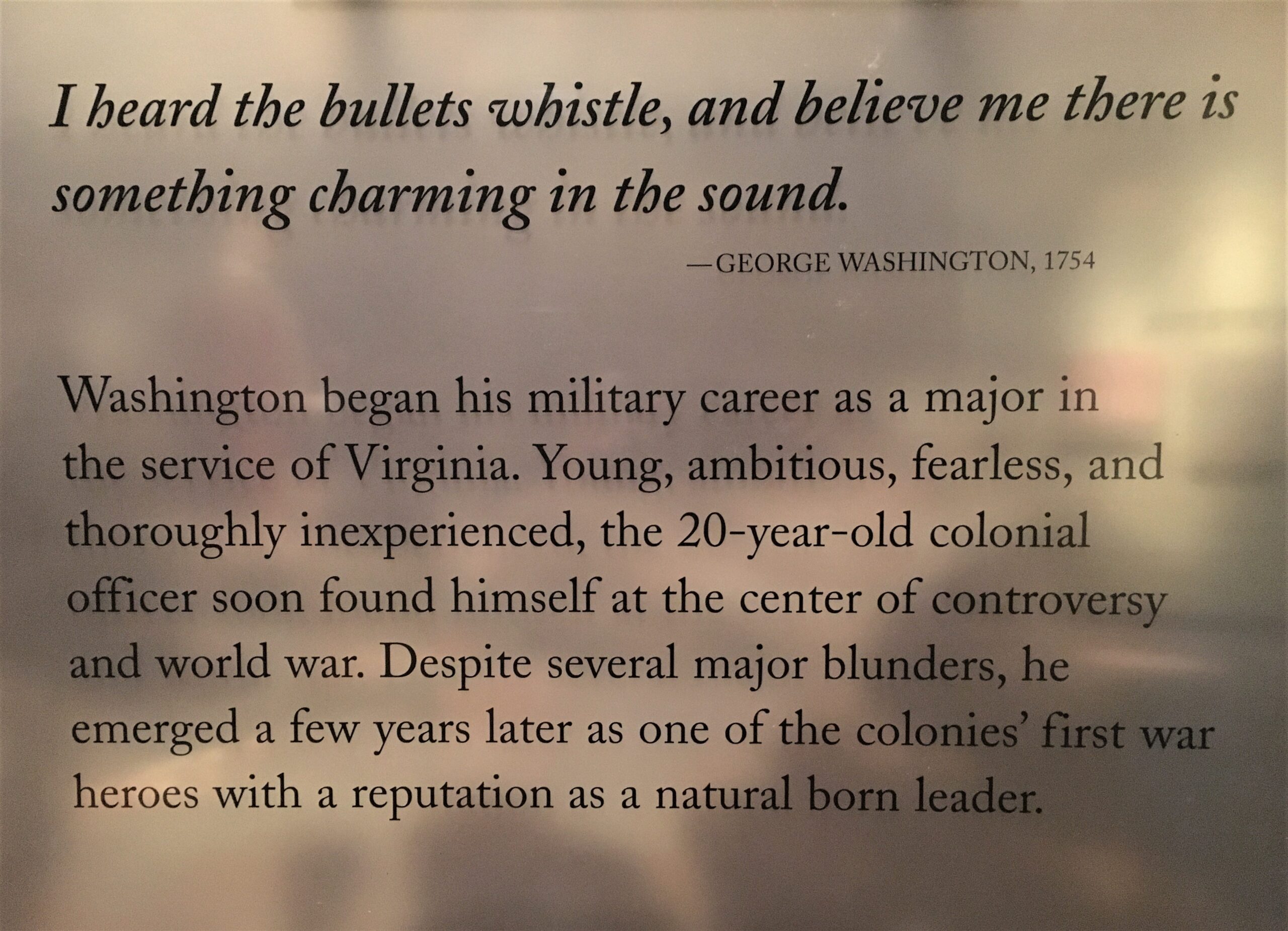

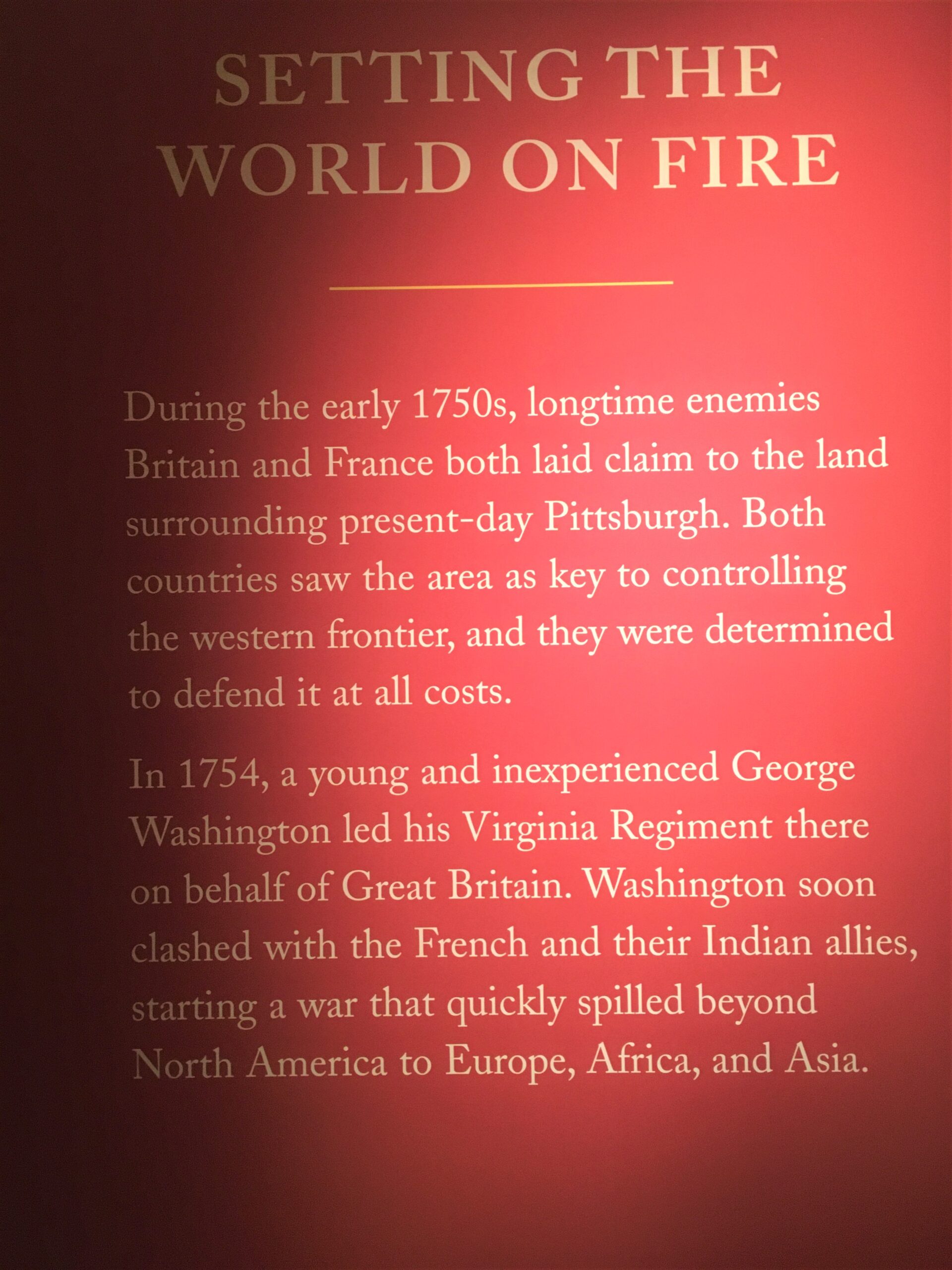

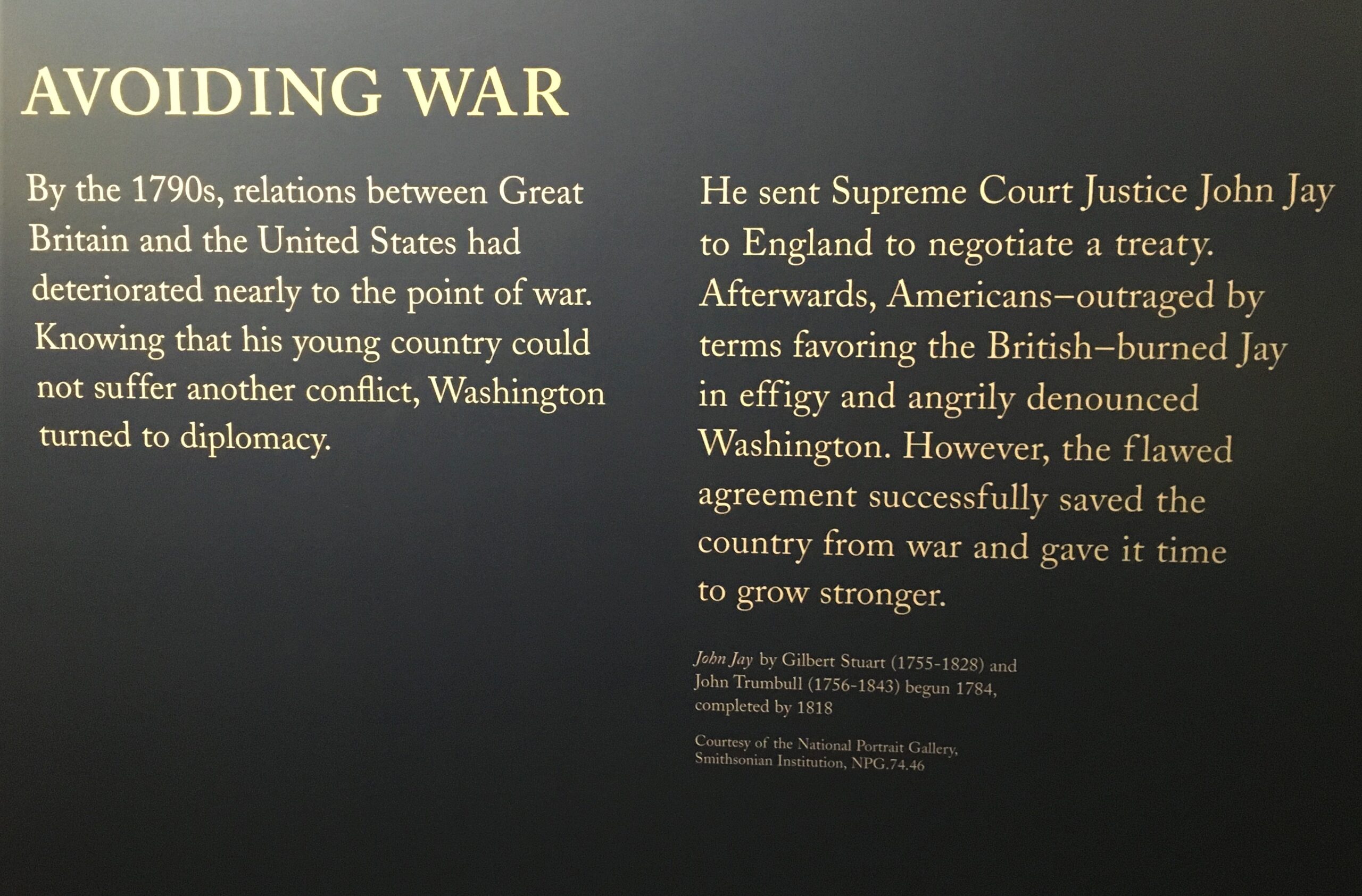

I don’t know about you, but we certainly never learned in school

that George Washington started the French and Indian War!!

It lasted for seven years!

President George Washington died an excruciating death at 67 years old. There were a few signs up in the museum recalling it, but it was dark and many came out blurry and they didn’t share the full story, so I’ve added the following I discovered at pbs.org:

It was a house call no physician would relish. On Dec. 14, 1799, three doctors were summoned to Mount Vernon in Fairfax County, Va., to attend to a critically ill, 67-year-old man who happened to be known as “the father of our country.”

On the afternoon of Dec. 13, a little more than 30 months into his retirement, George Washington complained about a cough, a runny nose and a distinct hoarseness of voice. He had spent most of the day on horseback in the frigid rain, snow and hail, supervising activities on his estate. Late for dinner and proud of his punctuality, Washington remained in his damp clothes throughout the meal.

By 2 a.m. the following morning, Washington awoke clutching his chest with a profound shortness of breath. His wife Martha wanted to seek help but Washington was more concerned about her health as she had only recently recovered from a cold herself. Washington simply did not want her leaving the fire-warmed bedroom for the damp, cold outside. Nevertheless, Martha asked her husband’s chief aide, Col. Tobias Lear, to come into the room. Seeing how ill the general was, Col. Tobias immediately sent for Dr. James Craik, who had been Washington’s physician for more than 40 years, and the estate’s overseer, George Rawlins, who was well practiced in the art of bloodletting.

Only a few hours later, 6 a.m., Washington developed a pronounced fever. His throat was raw with pain and his breathing became even more labored.

At 7:30 a.m., Rawlins removed 12 to 14 ounces of blood, after which Washington requested that he remove still more. Following the procedure, Col. Lear gave the patient a tonic of molasses, butter and vinegar, which nearly choked Washington to death, so inflamed were the beefy-red tissues of his infected throat.

American history buffs know so much about George Washington’s final illness because of a wealth of primary source documents as well as the herculean efforts of Dr. David Morens, an epidemiologist and the Senior Advisor to the Director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Morens wrote about these harrowing last hours for the New England Journal of Medicine in 1999. (1999; 341: 1845-1849). Another fascinating account of Washington’s medical history can be found in a 1933 issue of the Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine written by Dr. J.H. Mason Knox Jr. (1933; 1: 174-191). And even more intriguing is a long letter about Washington’s last illness, written by Col. Tobias as the events unfolded.

This 12-page letter is a treasured document at the William Clements Library at the University of Michigan. Another handwritten copy of these notes reposes in the University of Virginia Library.

Dr. Craik entered Washington’s bedchamber at 9 a.m. After taking the medical history, he applied a painful “blister of cantharides,” better known as “Spanish fly,” to Washington’s throat. The idea behind this tortuous treatment was based on a humoral notion of medicine dating back to antiquity called “counter-irritation.” The blisters raised by this toxic stuff would supposedly draw out the deadly humors causing the General’s throat inflammation.

At 9:30 a.m., another bloodletting of 18 ounces was performed followed by a similar withdrawal at 11 a.m. At noon, an enema was administered. Attempts at gargling with a sage tea, laced with vinegar were unsuccessful but Washington was still strong enough to walk about his bedroom for a bit and to sit upright in an easy chair for a few hours. His real challenge was breathing once he returned to lying flat on his back in bed.

Dr. Craik ordered another bleeding. This time, 32 ounces were removed even though Elisha Cullen Dick, the second physician to arrive at Mount Vernon, objected to such a heroic measure. A third doctor, Gustavus Richard Brown, made it to the mansion at 4 p.m. He suggested a dose of calomel (mercurous chloride) and a tartar emetic (antimony potassium tartrate), guaranteed to make the former president vomit with a vengeance.

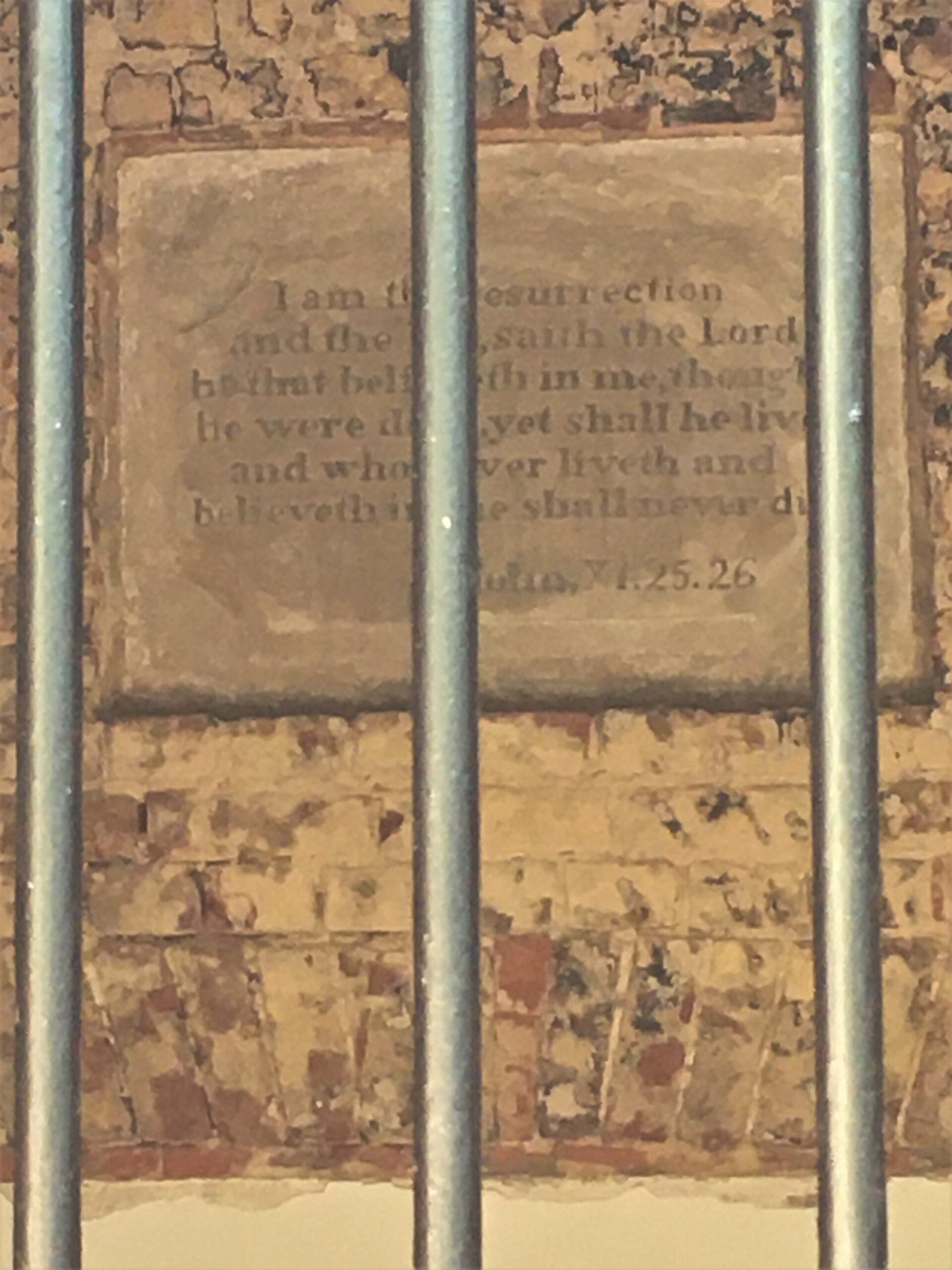

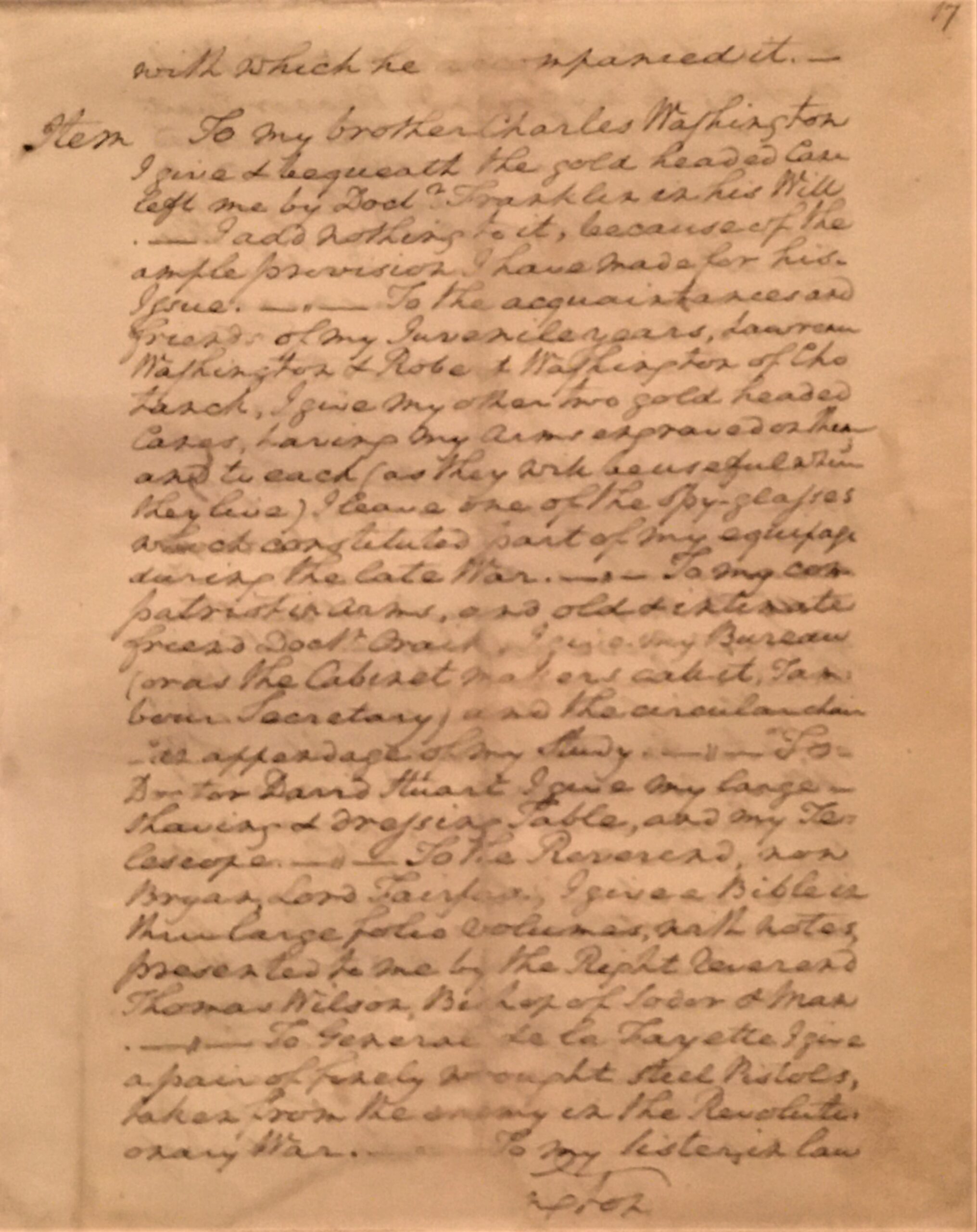

After the fourth bloodletting, Washington appeared to rally somewhat. At 5 p.m., he was having an easier time swallowing and even had the energy to examine his last will and testament with Martha. Soon enough, he was again struggling for air. He told Dr. Craik: “Doctor, I die hard; but I am not afraid to go; I believed from my first attack that I should not survive it; my breath can not last long.” Ever the gentleman, even in extremis, the General made a point of thanking all three doctors for their help.

By 8 p.m., blisters of cantharides were applied to his feet, arms and legs while wheat poultices were placed upon his throat with little improvement. At 10 p.m., Washington murmured some last words about burial instructions to Col. Lear. Twenty minutes later, Col. Lears’ notes record, the former president settled back in his bed and calmly took his pulse. At the very end, Washington’s fingers dropped off his wrist and the first president of our great Republic took his final breath. At the bedside were Martha Washington, his doctor, James Craik, Tobias Lear, his valet, Christopher Sheels, and three slave housemaids named Caroline, Molly and Charlotte.

Washington’s physicians, as doctors are wont to do, argued heatedly over the precise cause of death. Dr. Craik insisted that it was “inflammatory quinsy,” or peritonsillar abscess. Dr. Dick rejected such a possibility and offered three alternative diagnoses: stridular suffocatis (a blockage of the throat or larynx), laryngea (inflammation and suppuration of the larynx), or cynanche trachealis. The last arcane medical diagnosis (from the Latin, for “dog strangulation”), which prevailed as the accepted cause of Washington’s death for some time, referred to an inflammation and swelling of the glottis, larynx and upper trachea severe enough to obstruct the airway.

Back in 1799, Washington’s physicians justified the removal of more than 80 ounces of his blood (2.365 liters or 40 percent of his total blood volume) over a 12-hour period in order to reduce the massive inflammation of his windpipe and constrict the blood vessels in the region. Theories of humoralism and inflammation aside, this massive blood loss — along with the accompanying dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and viscous blood flow — could not have helped the president’s dire condition.

A fourth physician, William Thornton (who also designed the U.S. Capitol building), arrived after Washington succumbed. Thornton had expertise in the tracheotomy procedure, an extremely rare operation at the time that was performed only in emergencies and with occasional success. Dr. Dick, too, advocated this procedure — rather than the massive bloodletting — but given the primitive nature of surgical science in 1799, it is doubtful it would have helped much.

In the 215 years since Washington died, several retrospective diagnoses have been offered ranging from croup, quinsy, Ludwig’s angina, Vincent’s angina, diphtheria, and streptococcal throat infection to acute pneumonia. But Dr. Morens’s suggestion of acute bacterial epiglottitis seems most likely. In the end, we will never really know, which constitutes half of the fun enjoyed by doctors who argue over the final illnesses of historical figures.

At this late date, it is all too easy to criticize Washington’s doctors. Indeed, even in real time and for decades thereafter, critics complained that the physicians bled Washington to death. But the truth of the matter is that they did the best they could, against a pathologically implacable foe, using now antiquated and discredited theories of medical practice.

The president’s last hours must have been agonizing to watch and, of course, to experience. Like any human being, General Washington hoped his physicians would help him to an easy death. Between the massive bloodletting, the painful blistering treatments, and the awful sensation of suffocation, this was not at all possible.

What a horrific way for the Father of our Country to end his life!

If you can read it, you’re better than me. : )

There was nothing and no one telling us that the place was closed until we started walking up to it!

It was hot. There wasn’t much to see in Old Town,

but the restaurant was cool and the Reubens were excellent!

Isn’t the street pretty?

That’s the real reason for the picture. : )

And there was nothing to indicate why it’s here.