George’s great grandfather, John Washington, was the first of the family to come to ‘America’ (what was then the British Colonies) when he and another family were granted 5,000 acres by the then ruling government of Virginia in 1674. John named his small house and the surrounding land, Little Hunting Creek Plantation. John bequeathed the home to his son Lawrence in 1677, who in turn, passed it to his daughter Mildred in 1698.

In 1726, Mildred sold the estate to her brother, Augustine, George Washington’s father (George was two years old). By then, the original house was no more, so Augustine built the main part of the current plantation house (one-and-a-half stories).

In 1740, Augustine left the estate to his older son (also named Lawrence, lest you get confused as I did 😊); who was George’s older half-brother by 14 years. It was this second Lawrence who renamed the estate Mount Vernon, after a famed English naval officer whom he greatly admired – Admiral Edward Vernon.

Owned the home from 1740 until 1752 when he died at 34 of TB

Mount Vernon came into George’s hands in 1761, following the deaths of his brother, Lawrence and Lawrence’s two heirs – his widow and their daughter.

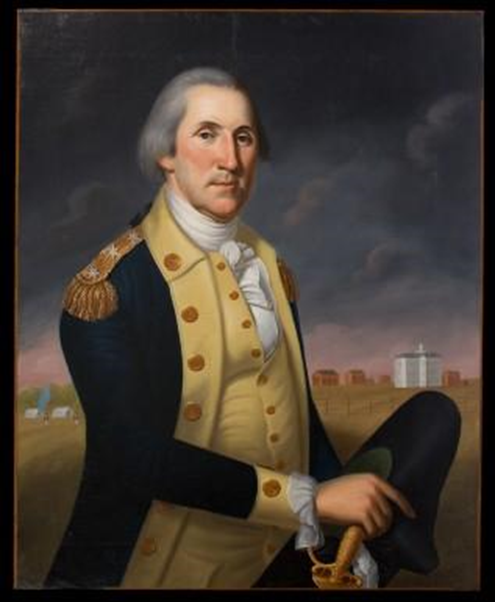

George lived most of his life on Mount Vernon, learning farming and how to be a cultured member of society from his brother. Then, in 1753, at age 27, George began his military career.

He didn’t make Mount Vernon his home until 1759, after he married widow and mother of two, Martha Dandridge Custis (one of the wealthiest men in Virginia who died seven years into the marriage when Martha was but twenty-six years old) – the future first First Lady of the United States of America. Fun Fact! Her first husband’s home was named “The White House”! She brought along two children from her first marriage. Did you notice the seeming discrepancy in dates? That’s because George leased the house from his sister-in-law for two years, until she passed in 1761 and he inherited.

Owned the home from 1761-1799 when he died

During those years he leased the home, he went ahead and began expanding, first by raising the roof and adding a story, making it 2 ½ stories. It wasn’t until 1774, that he began the tasks of adding the north and south wings, the cupola and piazza, eventually making the home as we see it today. It’s 11,028 square feet and boasts 21 rooms, and he supervised nearly every detail, even as he was serving in the Revolutionary War and as our first president.

When George died in 1799, the estate fell to Martha. George left behind no children, so consequently there were no heirs. Did you know he never fathered a child? The two Martha brought into their marriage from her first husband, Martha Parke Custis (known as Patsy) and John Parke Custis (known as Jacky). Patsy was two when her mother remarried, but suffered from seizures and died suddenly at age 17 in 1773. Jacky was four at the time of the marriage, but Jack basically left the family in favor of creating his own family. He eventually met up with George at Yorktown at the end of the Revolutionary War, but died of ‘camp fever’ along with hundreds other men. It was 1781.

Owned the home from 1799-1802 when she died

Martha lived at the mansion until 1802, at which time, the estate was passed to Bushrod Washington, the eldest son of George’s brother, John Augustine. Bushrod was an accomplished judge who served on the US Supreme Court beginning in 1798. He wasn’t really interested in the place and it began to fall into disrepair. Sightseers also contributed to the physical decline of the mansion and grounds.

Owned the home from 1802-1829.

In 1829, Bushrod died without heirs and bequeathed the estate to his nephew, John Augustine Washington II, who owned the home until 1832, when he died, leaving the estate to his wife, Jane Charlotte Blackburn Washington.

I was unable to find a picture of John, II ☹

Jane was active in managing Mount Vernon, even beyond a devastating fire in 1835 that destroyed George’s greenhouse and a portion of the enslaved living quarters. In 1841, she began to lease the estate to her son, John Augustine Washington III for $500/year.

She owned the home from 1832-1850

Jane’s son, John III owned the estate from 1850-1858, but he’d been running it for at least ten years prior to that. He was George Washington’s great-grand nephew. Even though he was very interested in the agricultural aspect of the estate, the estate’s total acreage had dropped from 8,000 during George’s lifetime to 1,200 over the years and wasn’t enough to sustain the family.

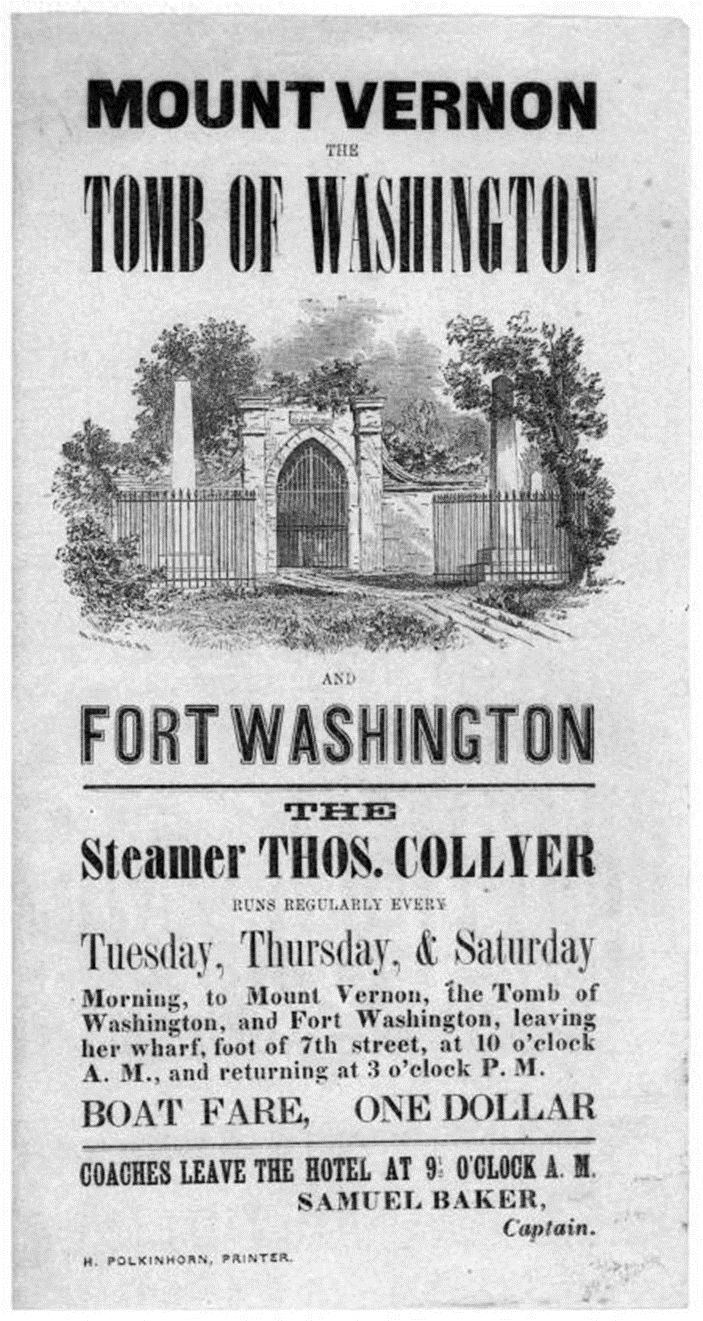

He attempted several things to bring in more money, including contracting with a steamboat company providing regular trips from Washington, DC three days a week, but the tourists only served to speed the deterioration of the mansion and grounds – even stealing wood and things as mementos.

Consequently, John made several unsuccessful attempts to sell Mount Vernon to the federal government and also the state of Virginia.

Owned the home from 1850-1858 when he sold it

Which brings us to the next piece of history.

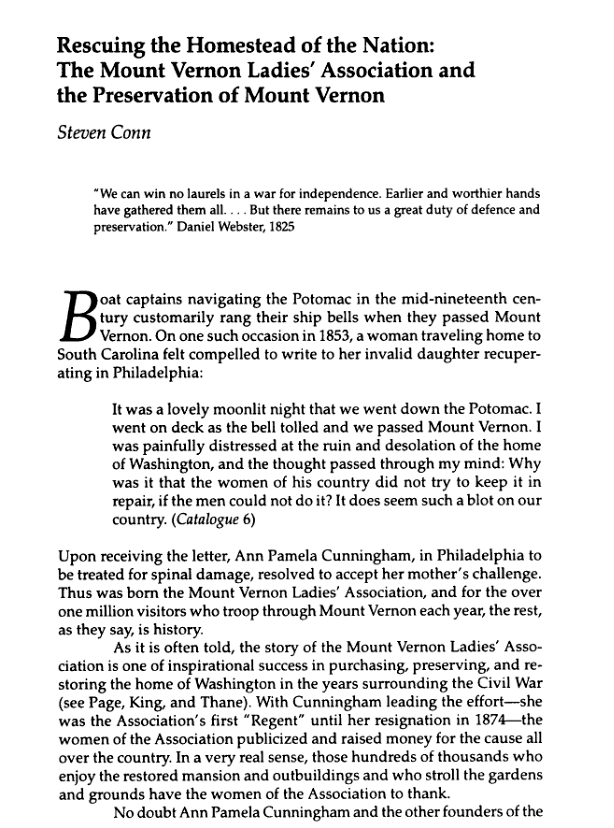

The forming of The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, who will own and run the estate from 1858 until the present. It started with a single innocent comment in a letter from mother to daughter:

The following article found on jstor.org describes how Ann Pamela Cunningham felt led to find a way to save Mount Vernon:

Initially writing under the pseudonym, “A Southern Matron,” Ann Pamela Cunningham challenged first the women of the South, and later the women of the entire country, to save the home of George Washington from dilapidation. After convincing John Augustine Washington III to sell the property, Cunningham and the organization she had founded, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, raised $200,000 (7.5 million today) to purchase the mansion and two hundred acres. The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association took over operation of the estate in 1860.

This is powerful evidence of how one person, in the right place, at the right time, speaking to the right person, can make an astonishing difference, that in this case carries on nearly 170 years later! What if Ann’s mother hadn’t been on that boat? What if she hadn’t written to her daughter? What if the letter got lost in the mail? What if Ann (did you catch that she was an invalid being treated for spinal damage at the time?) had simply sighed and said, “Oh, that’s too bad” when she read about the decomposing home of our first president? What if – – – we stepped up when God called to us? Sometimes, His Call is to write a simple letter. Sometimes, His Call involves much more.

During the Civil War (1861-65), it was the efforts of Ann Pamela Cunningham and her newly founded “Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union” who managed to save and preserve Mount Vernon from the ravages of war. According to mountvernon.org, Their efforts were helped by the fact that George Washington’s legacy was revered by soldiers fighting on both sides of the Civil War. Those fighting for the Confederacy viewed him as a native son of Virginia, which formally voted to secede from the United States in a referendum held on May 23, 1861. Soldiers fighting for the Union viewed Washington as the father of the country they were fighting to preserve.

Here are some facts about the house during George Washington’s time, I borrowed from mountvernon.org:

The Mansion is ten times the size of the average home in colonial Virginia.

At just over 11,000 square feet with two and a half stories and a full cellar, the Mansion dwarfed the majority of dwelling houses in late 18th-century Virginia. Most Virginians lived in one- or two-room houses ranging in size from roughly 200 to 1,200 square feet; most of these houses could have fit inside the 24×31 foot New Room. The ceilings of the Mansion vary in height—the average height on the first floor is 10’ 9”, while on the third floor it is 7’3”.

The expansions of the Mansion have preserved priceless information about the history of the structure and informed its preservation.

The south and north additions to the Mansion were built right up against the outside of the 1758 house. The 1758 siding was not removed and it is still visible in some of the hard-to-reach crawlspaces of the house. In these spaces, the original rusticated siding has been protected for over 230 years, as well as evidence for second-floor doors that led to porches on top of the one-story “closets” that were removed in the 1770s. The piazza roof covers part of the original shingles on the east slope of the 1770s roof.

Since the piazza roof was built just a year after the New Room addition roof was installed, the preserved shingles are brand new and still have their original red paint!

The cupola is topped with a weathervane in the shape of a dove of peace.

George Washington commissioned a weathervane for the Mansion’s new cupola while he was presiding over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. In his order to Philadelphia architect Joseph Rakestraw, Washington specified that the weathervane should

have a bird…with an olive branch in its Mouth…that it will traverse with the wind and therefore may receive the real shape of a bird.

Rakestraw constructed the weathervane from copper with an iron frame and lead head. Unfortunately, because of the increased air pollution around the Washington, D.C. area, the original dove of peace had to be permanently removed in 1993. Today an exact replica rests in its place.

The exterior of the Mansion is rusticated to look like stone – but it is actually made of yellow pine siding.

Rustication is a technique designed to shape wooden siding to appear to be stone. This is done first by notching the faces and beveling the edges of weatherboards to give them the appearance of cut stone blocks. Next, the siding was painted with oil paint. Finally, sand was thrown onto the wet paint, creating a rough stone-like texture.

Washington first rusticated the Mansion in 1758 to make it appear constructed of structural sandstone blocks, which were more expensive than wood or brick. In doing so, Washington preserved the house his father built, while making it appear in the same league with other more substantially-built—and expensive—houses.

The Washingtons hosted as many as 677 guests at the Mansion in 1798.

The Washingtons had many visitors at Mount Vernon, particularly after the Revolutionary War as Washington’s political stature grew. Many of these visitors were close friends, family members, or neighbors, but others were unknown to the Washingtons’. In 1797, Washington commented about a recent dinner “at which I rarely miss seeing strange faces; come, as they say, out of respect to me. Pray, would not the word curiosity answer as well?”

The steady pace of visitors continued after George Washington’s death in 1799. Martha Washington subsequently moved out of their shared bedchamber to a small room on the third floor. This room afforded her some privacy from the steady stream of visitors who continued to travel to Mount Vernon.

Today, as always, Mount Vernon receives no federal or state funding. It’s maintained in trust for the people of the United States by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, a private, non-profit organization (501c3) founded in 1853 by Ann Pamela Cunningham. They rely solely on ticket sales retail and dining purchases and donations.

The estate has hosted more than 80 million visitors over the past 162 years.