Lums Pond State Park, Bear, Delaware

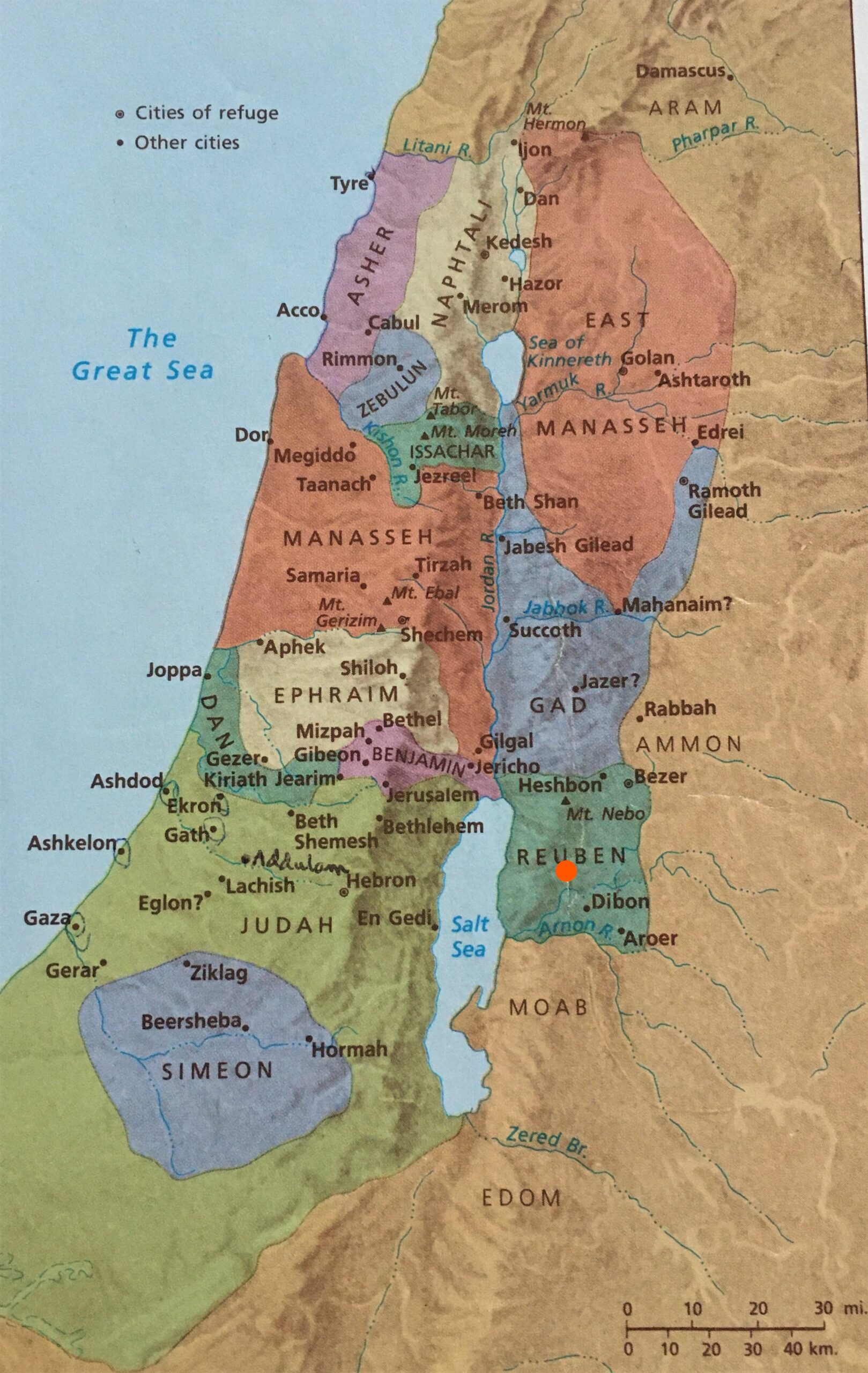

Reuben, you are my firstborn, my might, the first sign of my strength, excelling in honor, excelling in power. Turbulent as the waters (boiling water), you will no longer excel, for you went up onto your father’s bed, onto my couch and defiled it. ~ Genesis 49:1-4 My chronological Bible has given titles to each of the sons, and I’ll share them, just because. ‘Reuben the Unstable’. We’ve been reading about Reuben (son #1) and the high cost of his decision to spend one night with his father’s concubine, Bilhah, off and on for quite some time. As firstborn, he was entitled to become the leader of his family upon his father’s death, as well as receiving a double portion of the inheritance. In the end, Reuben’s descendants ended up playing only a secondary role in Jewish history, and finally, after forming a separate nation with nine other tribes, were conquered by the Assyrians and lost their identity forever through intermarriage. We don’t often stop to think about our actions. We don’t usually consider that one careless and/or selfish attitude of defiance or pride could change the course of our entire history – and beyond. Or that it could change the lives of others. One moment’s pleasure and suddenly, we’ve lost our way. Thank God, He is willing to forgive us and can still use us, if we but turn to Him in repentance!

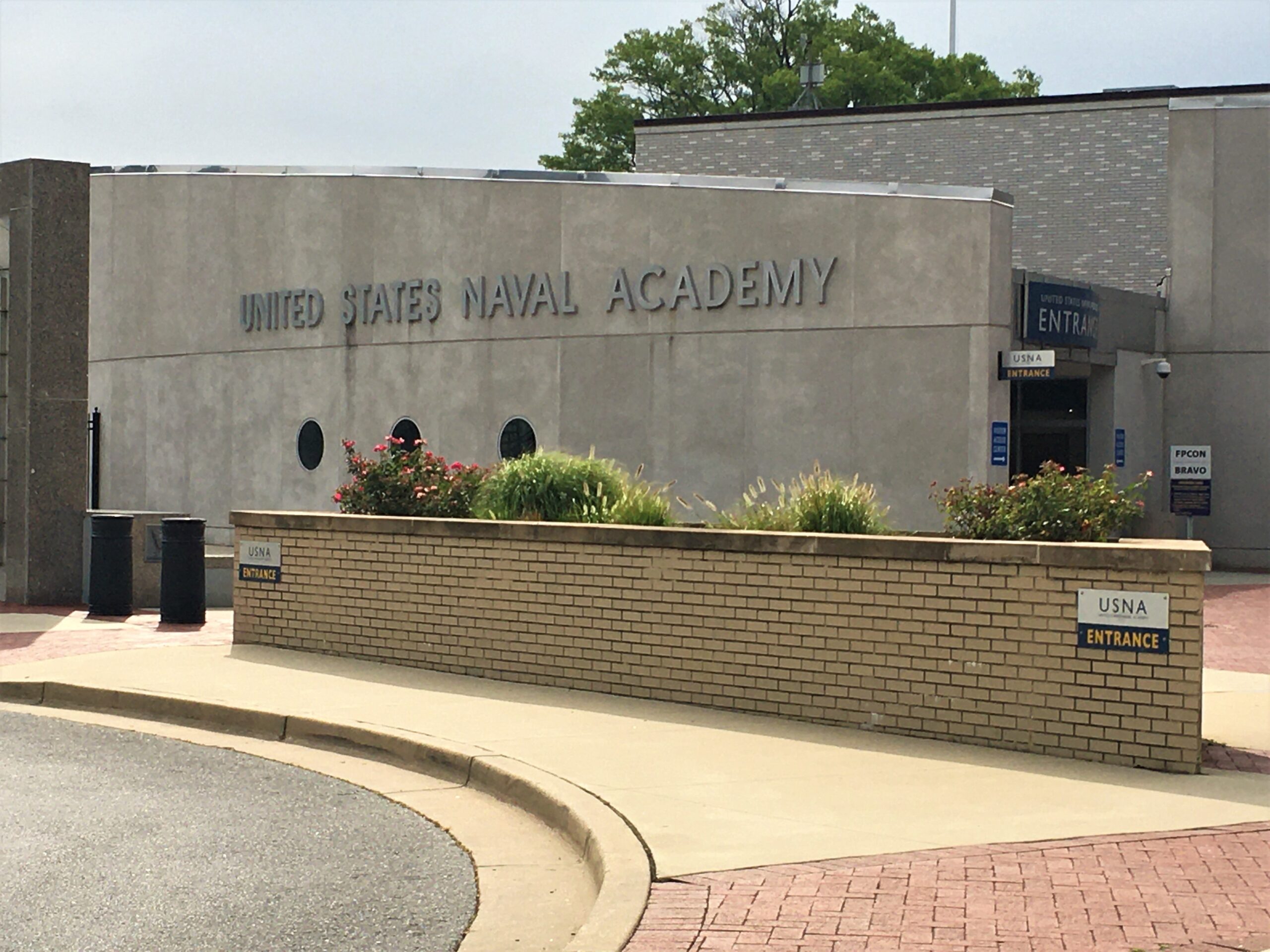

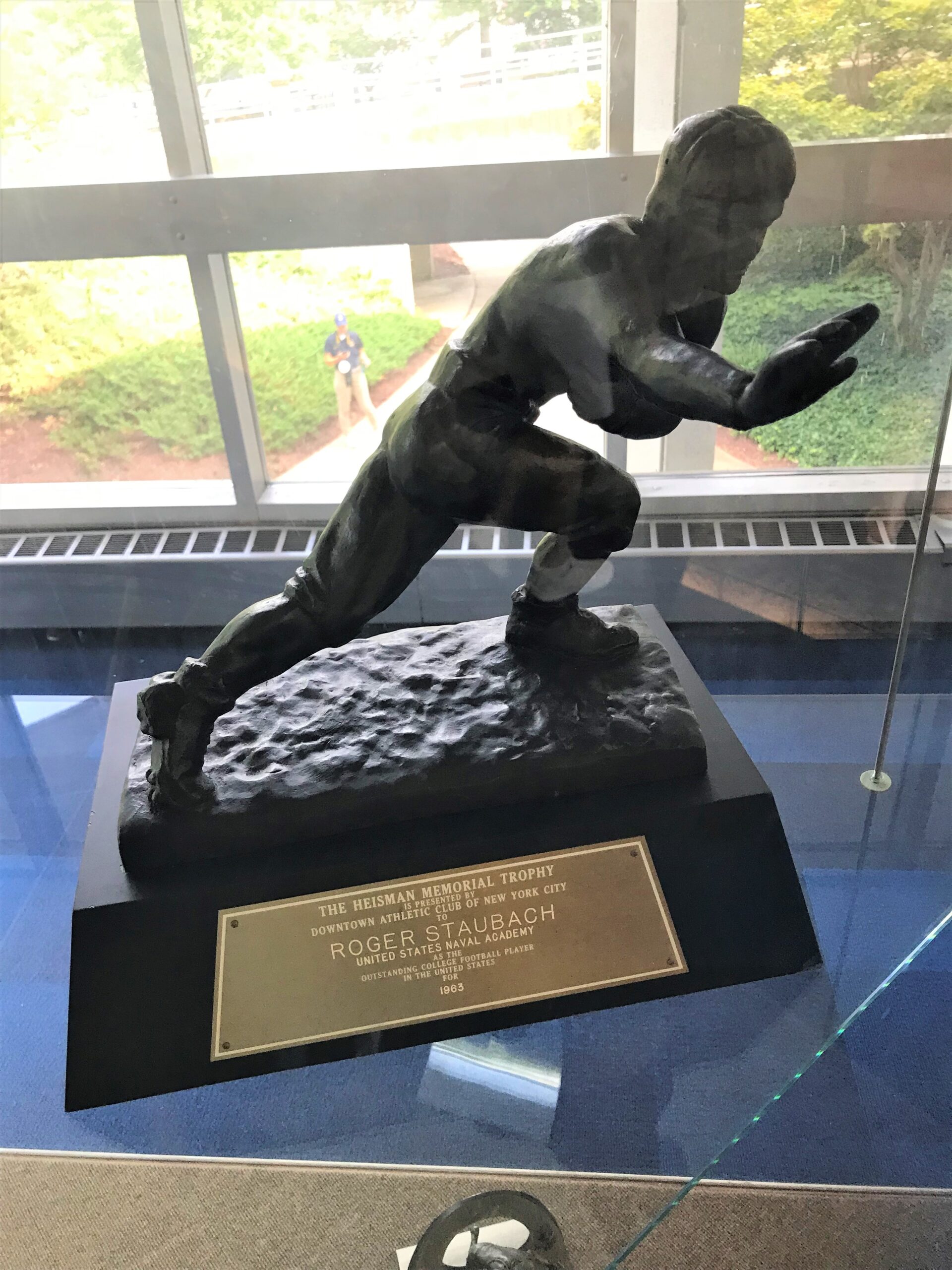

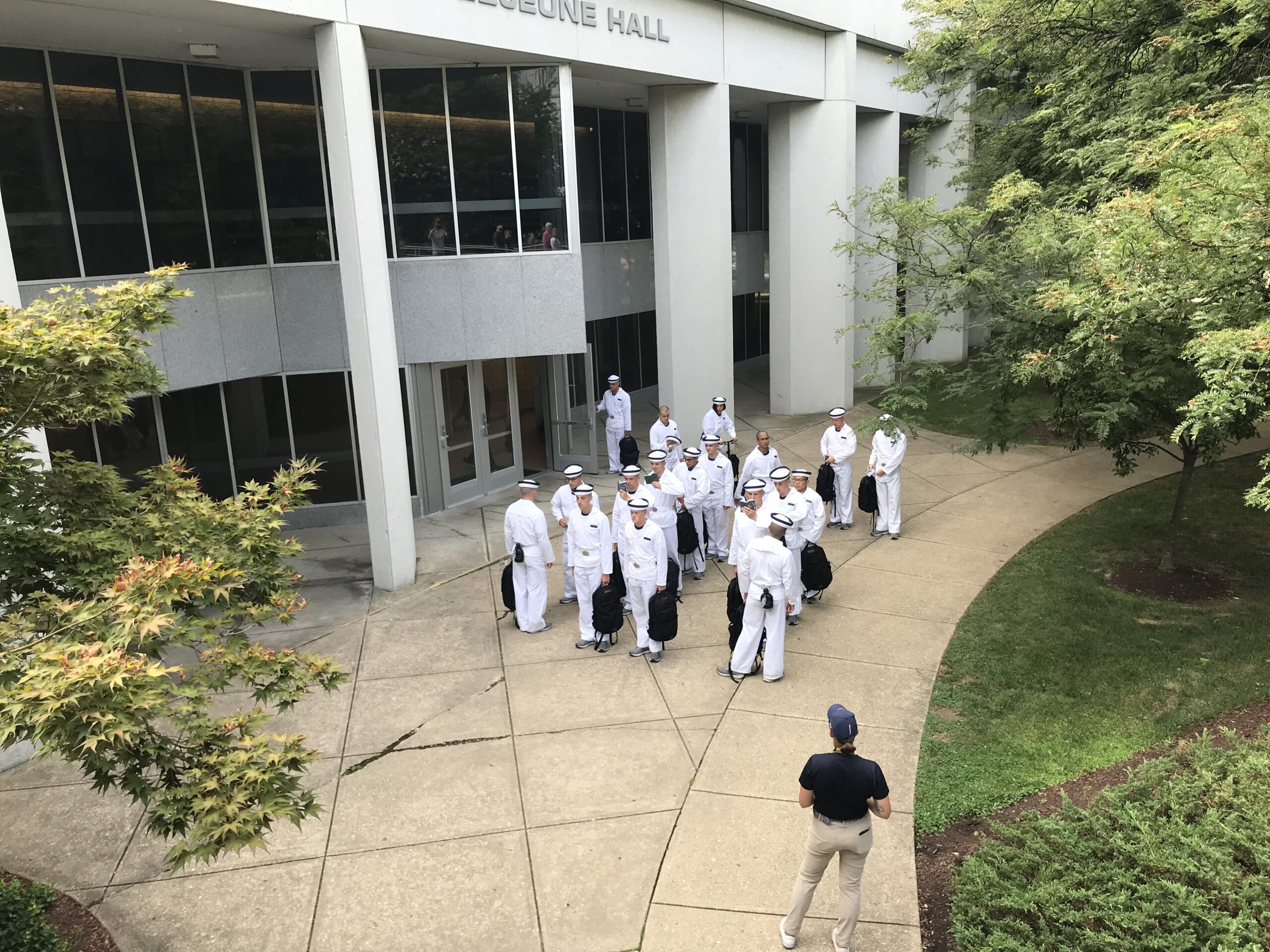

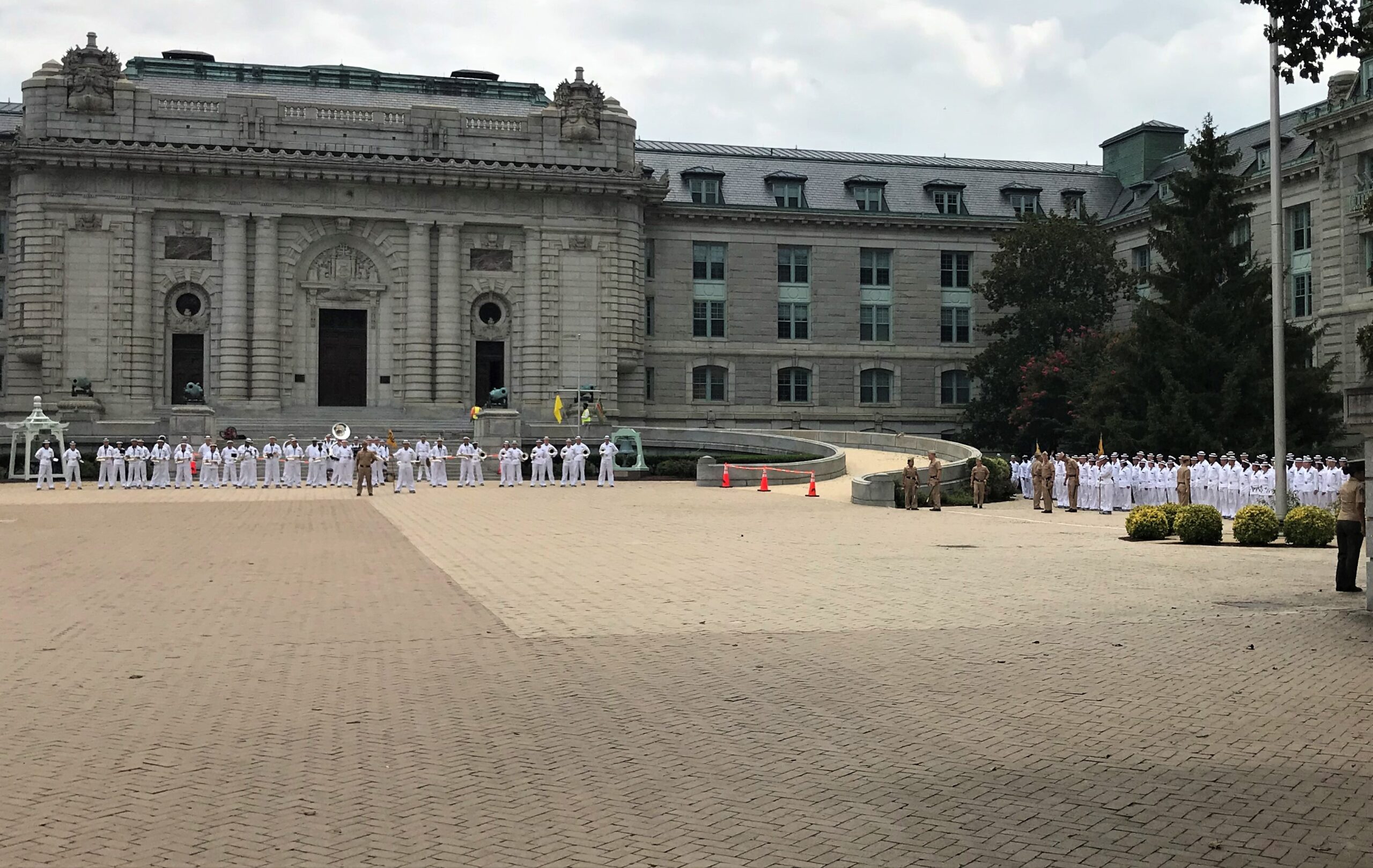

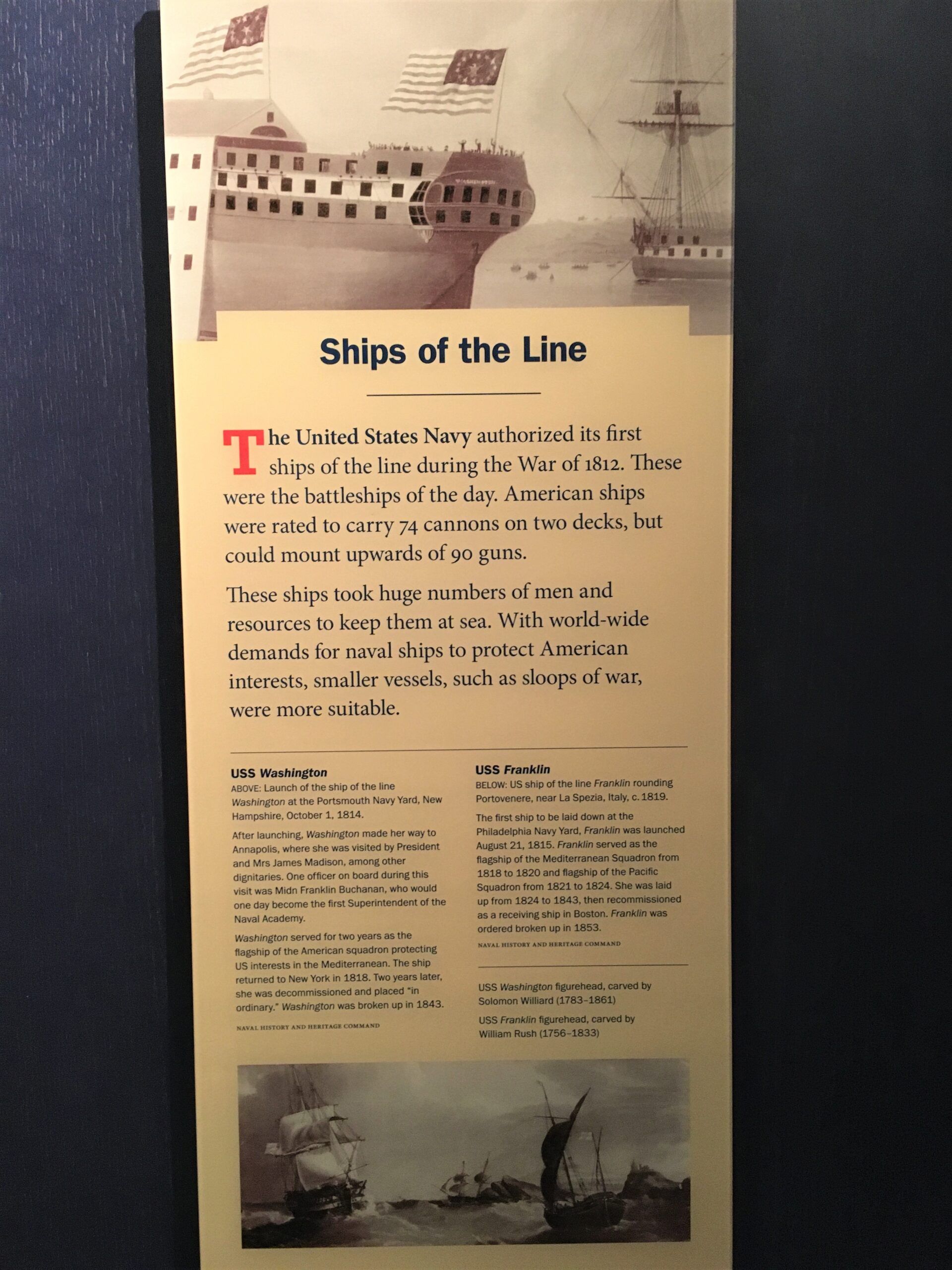

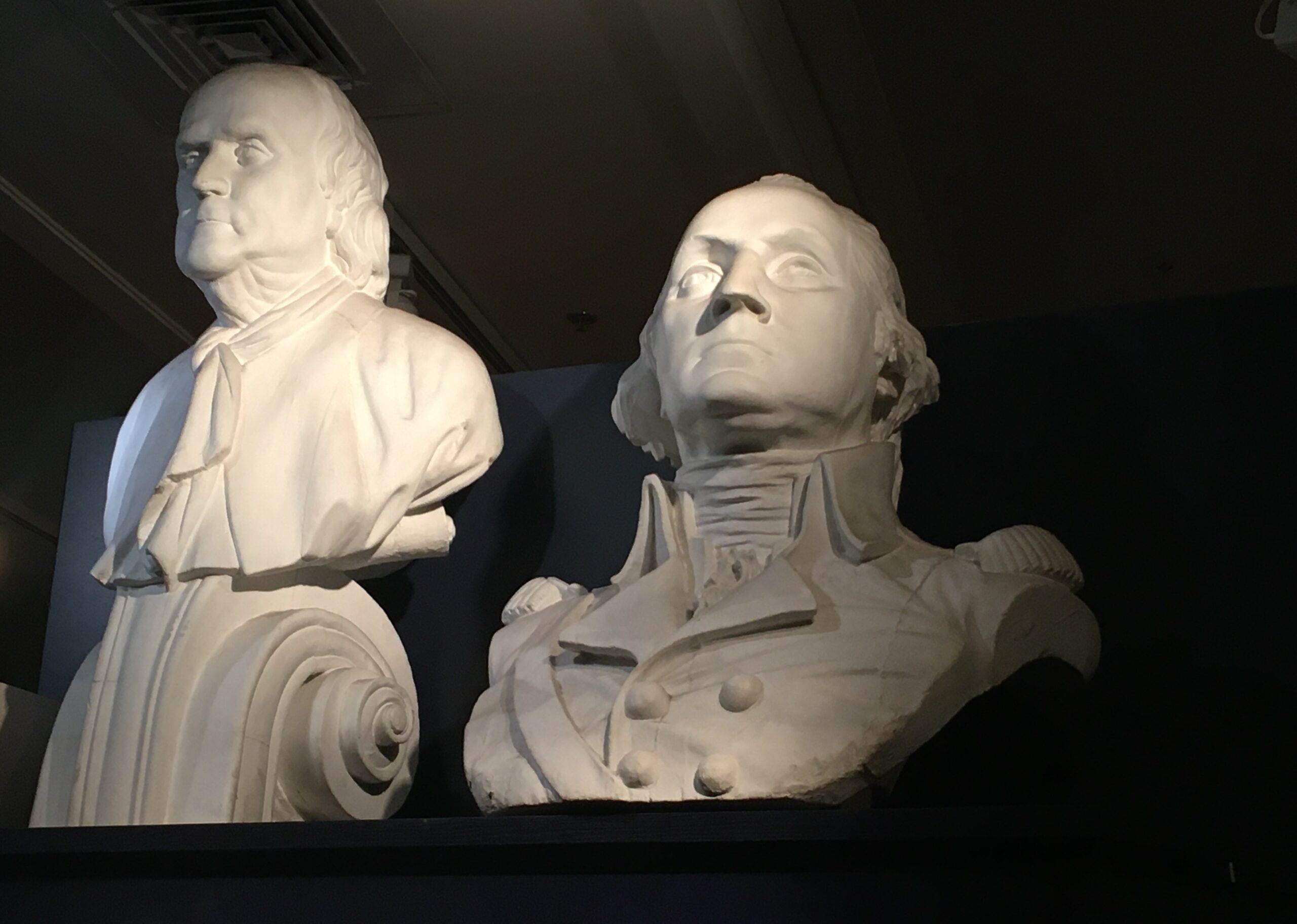

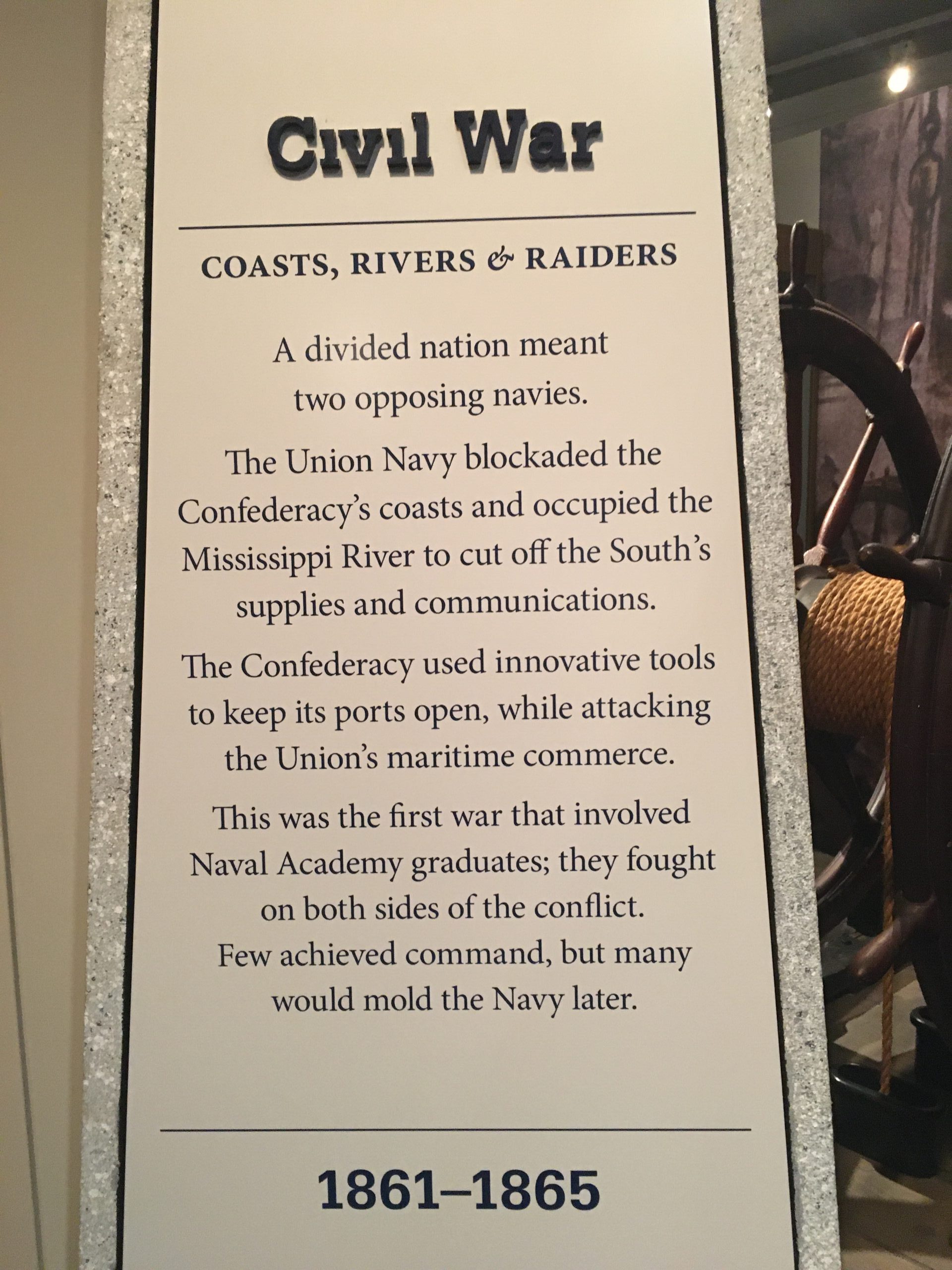

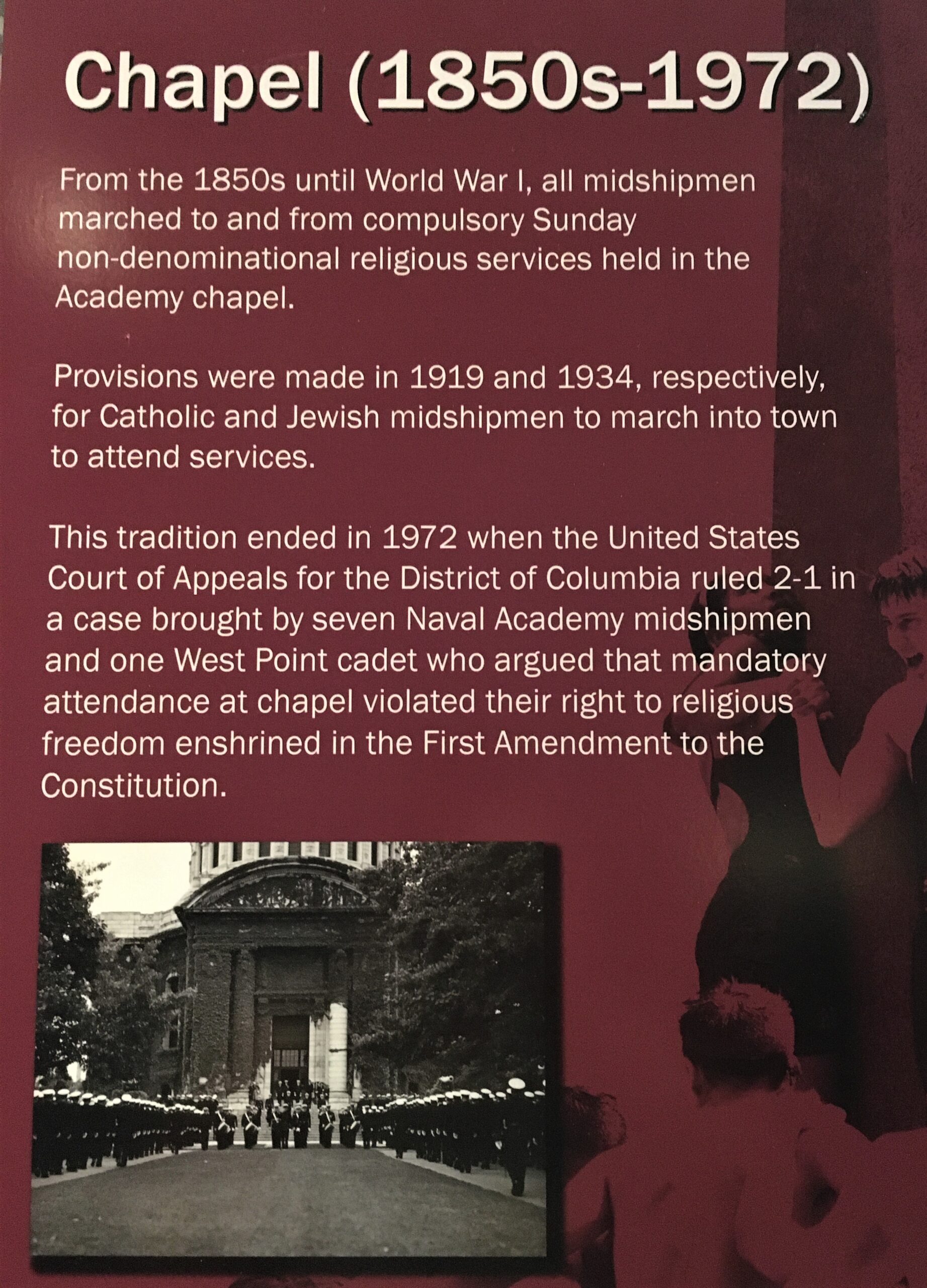

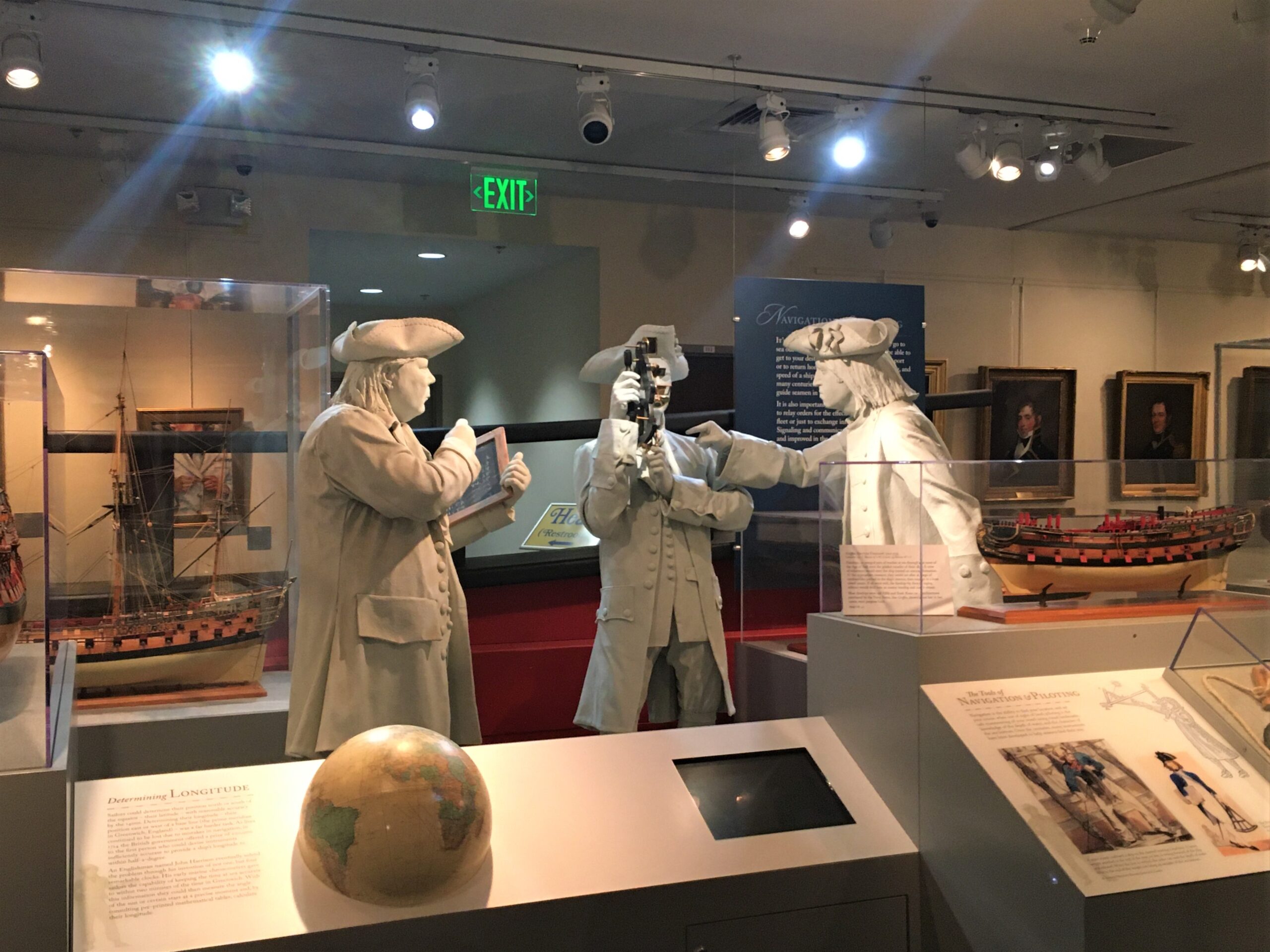

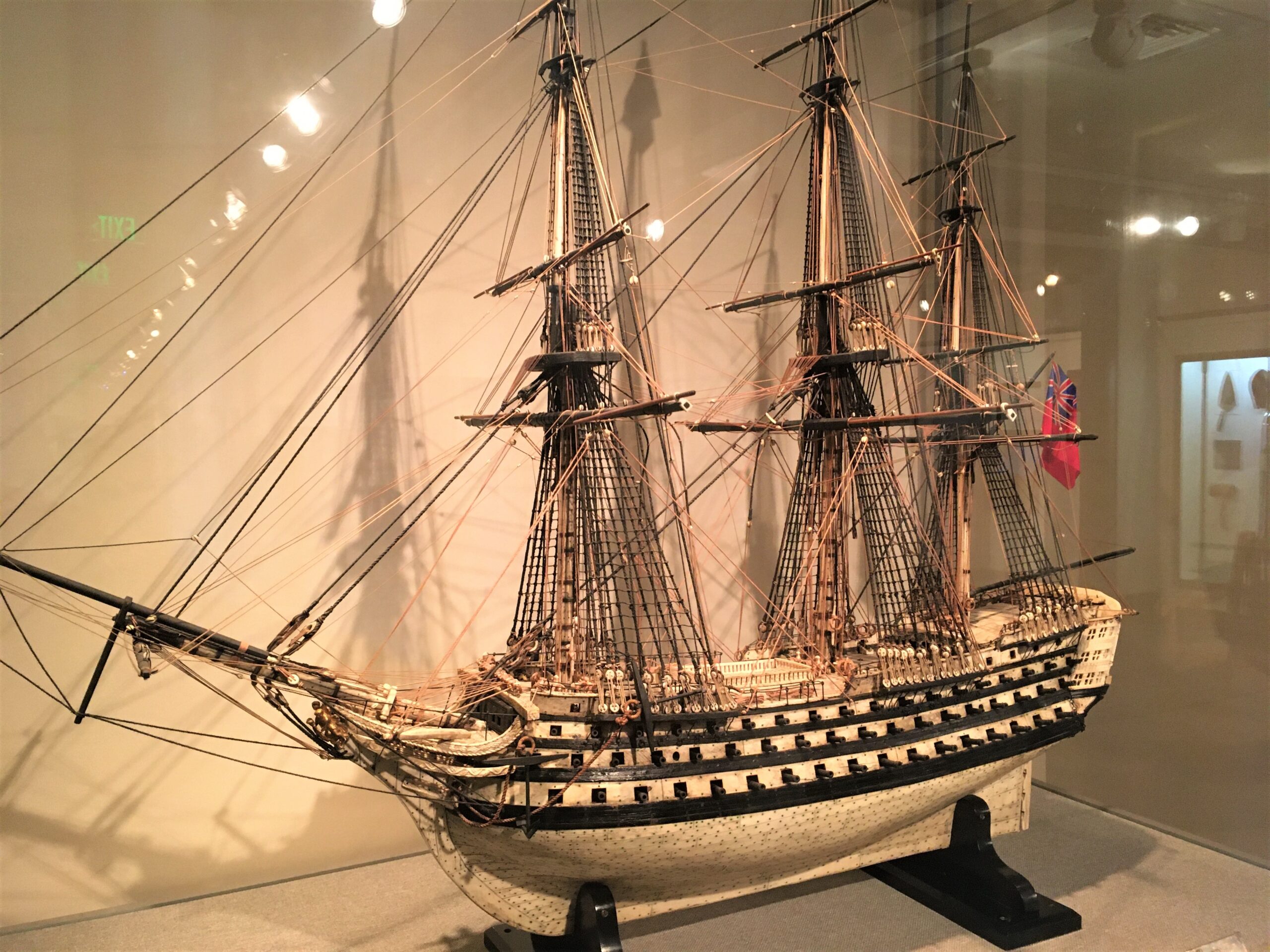

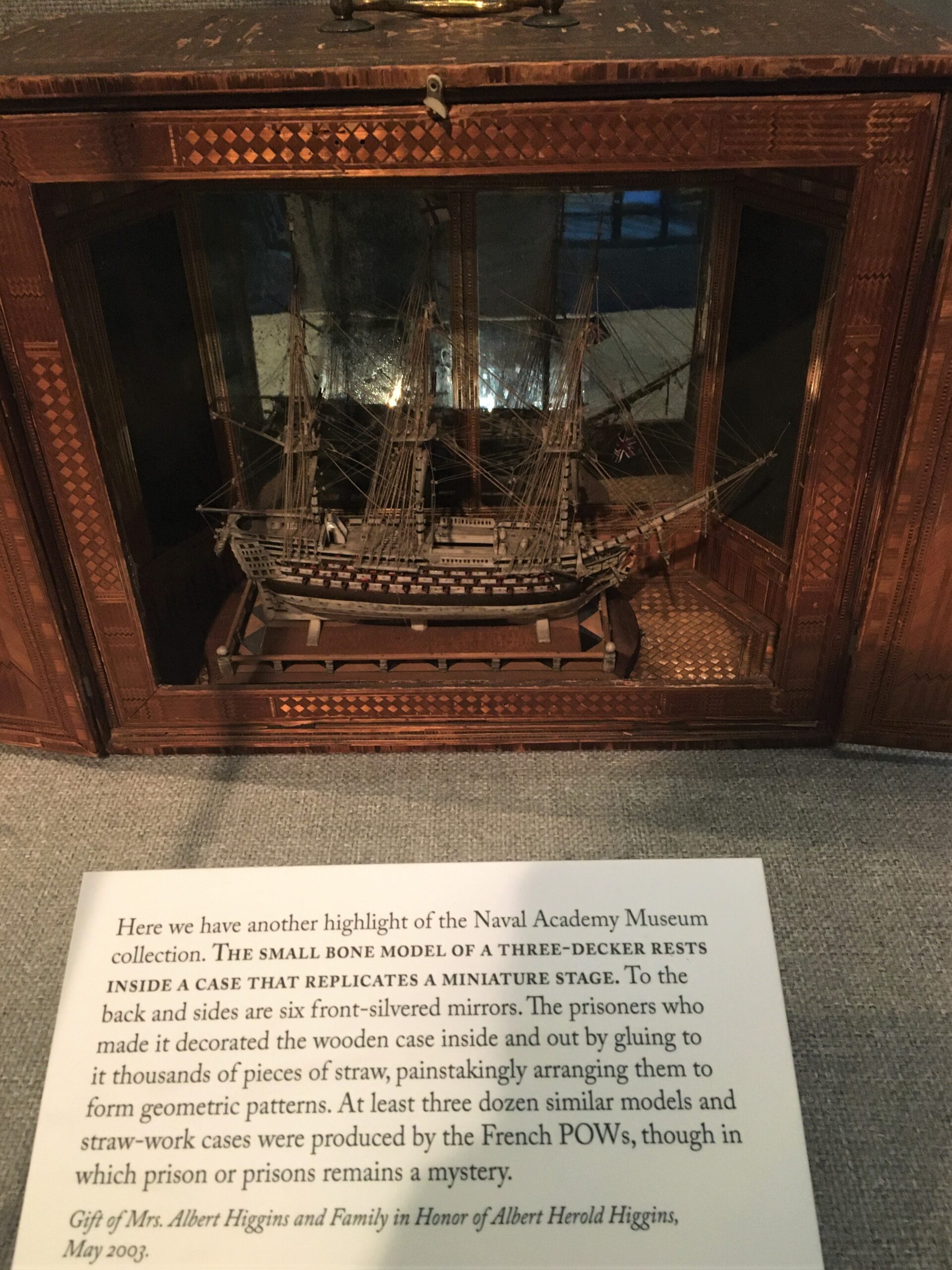

Blaine presented me with an option to take an overnight trip,and I accepted–immediately. 😊 So this morning, we drove over to Annapolis where we took a US Naval Academy guided tour, looked at their museum, a walk-about on our own, and watched the plebes (Freshmen) go through a drill. We had a wonderful time!

There was a row of them, all the same.

Still do sometimes, but today the downstairs was being used as sick bay.

No beds, just exams and some treatments.

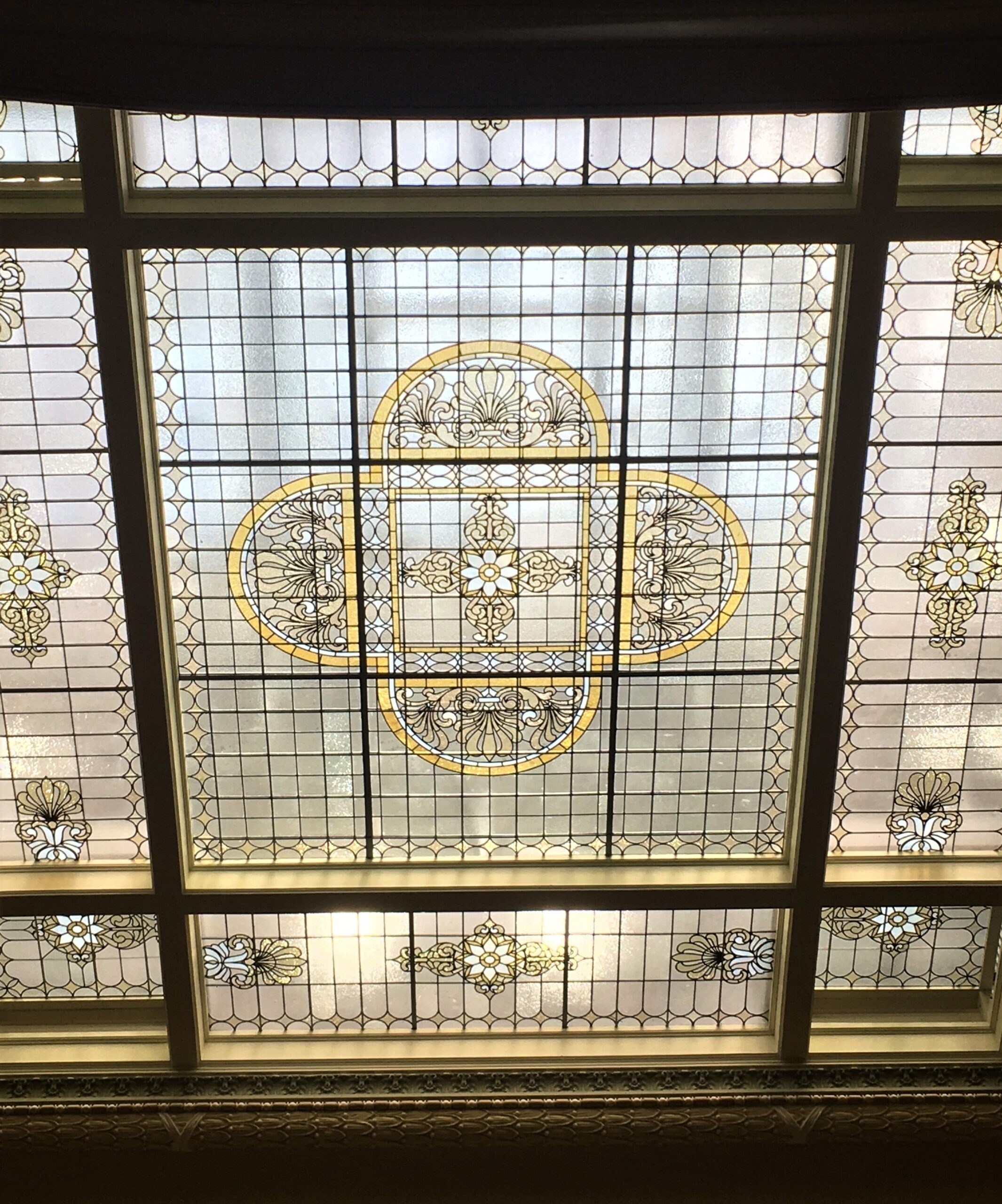

We got to go inside – Beautiful!!

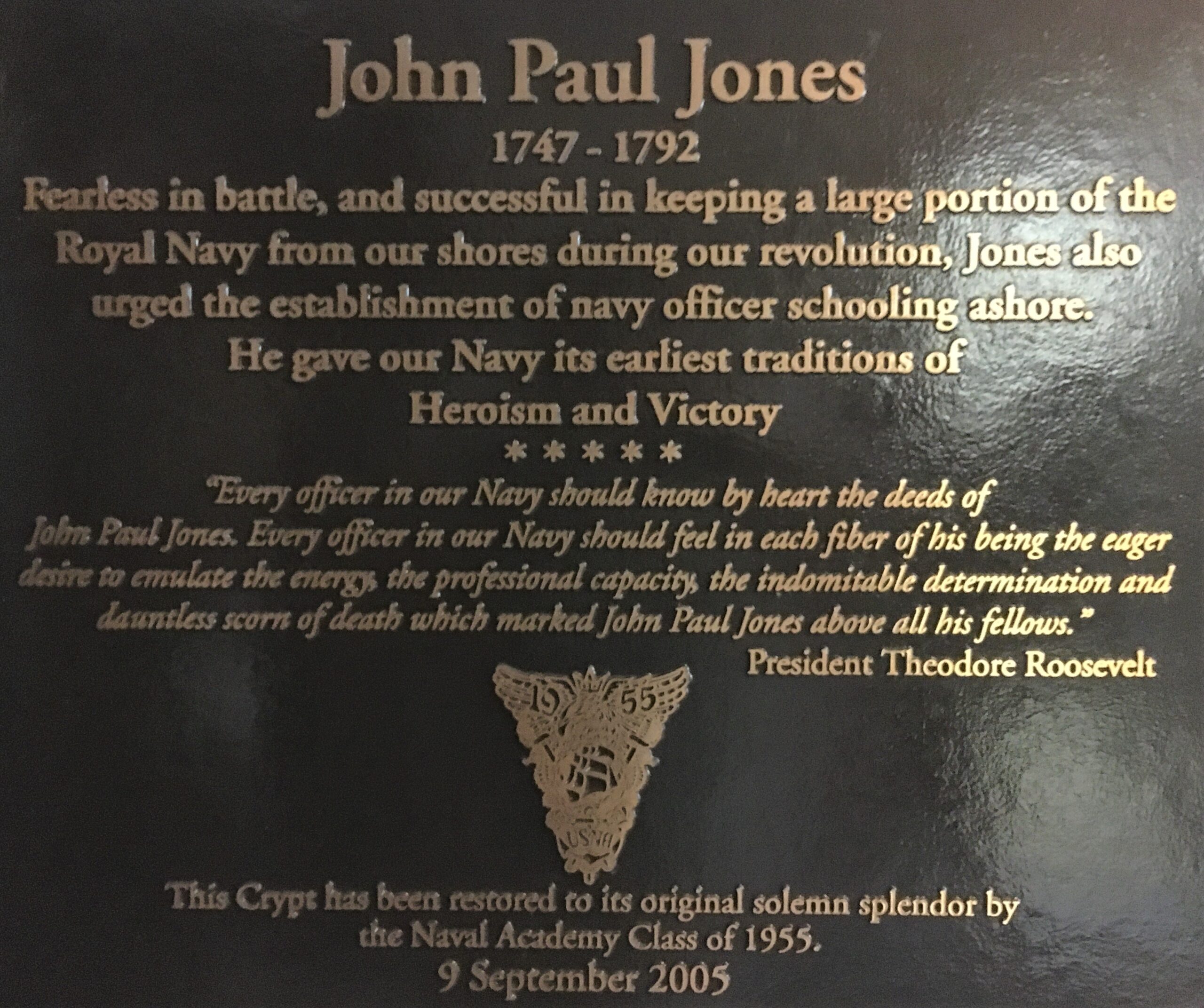

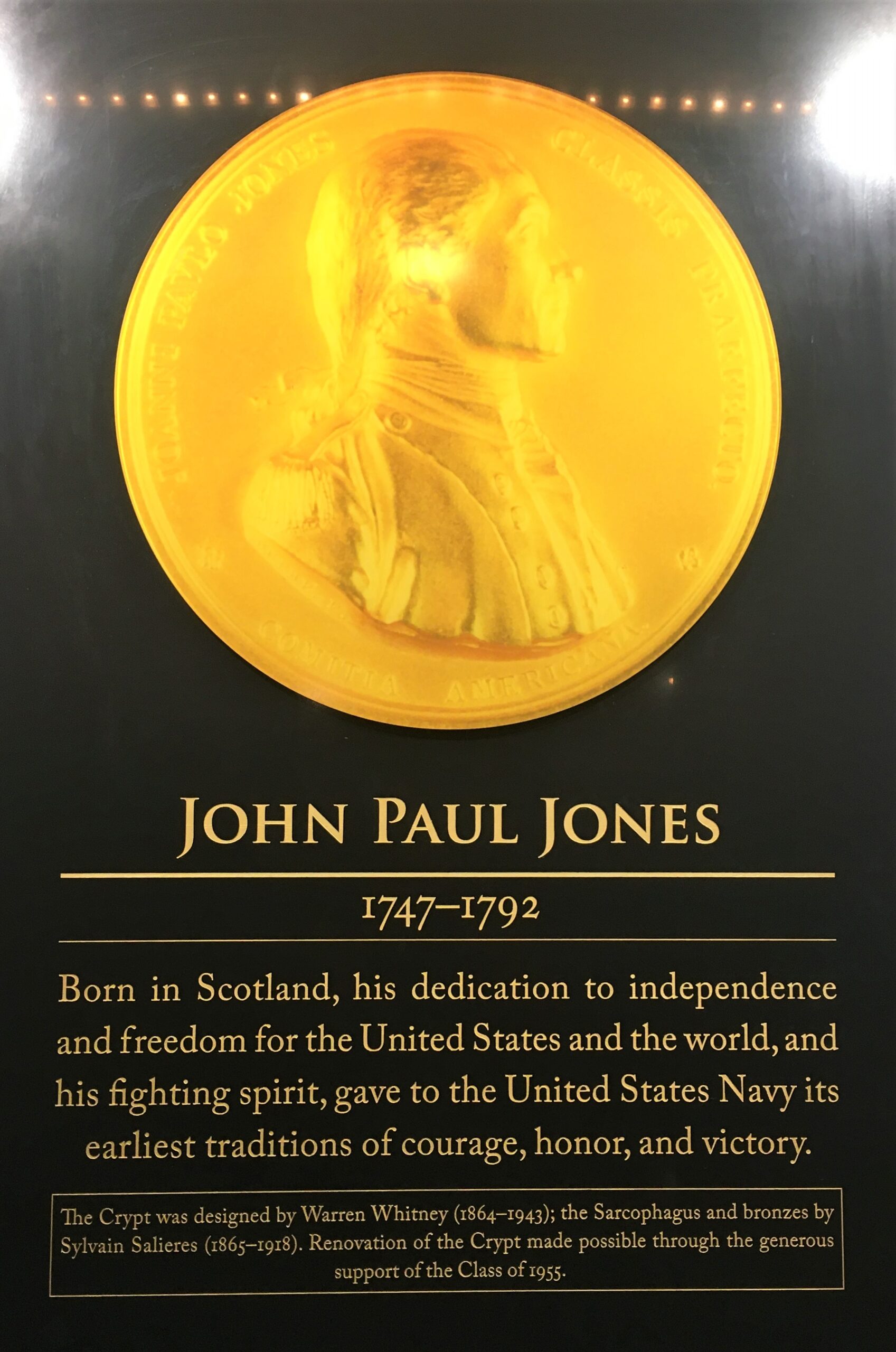

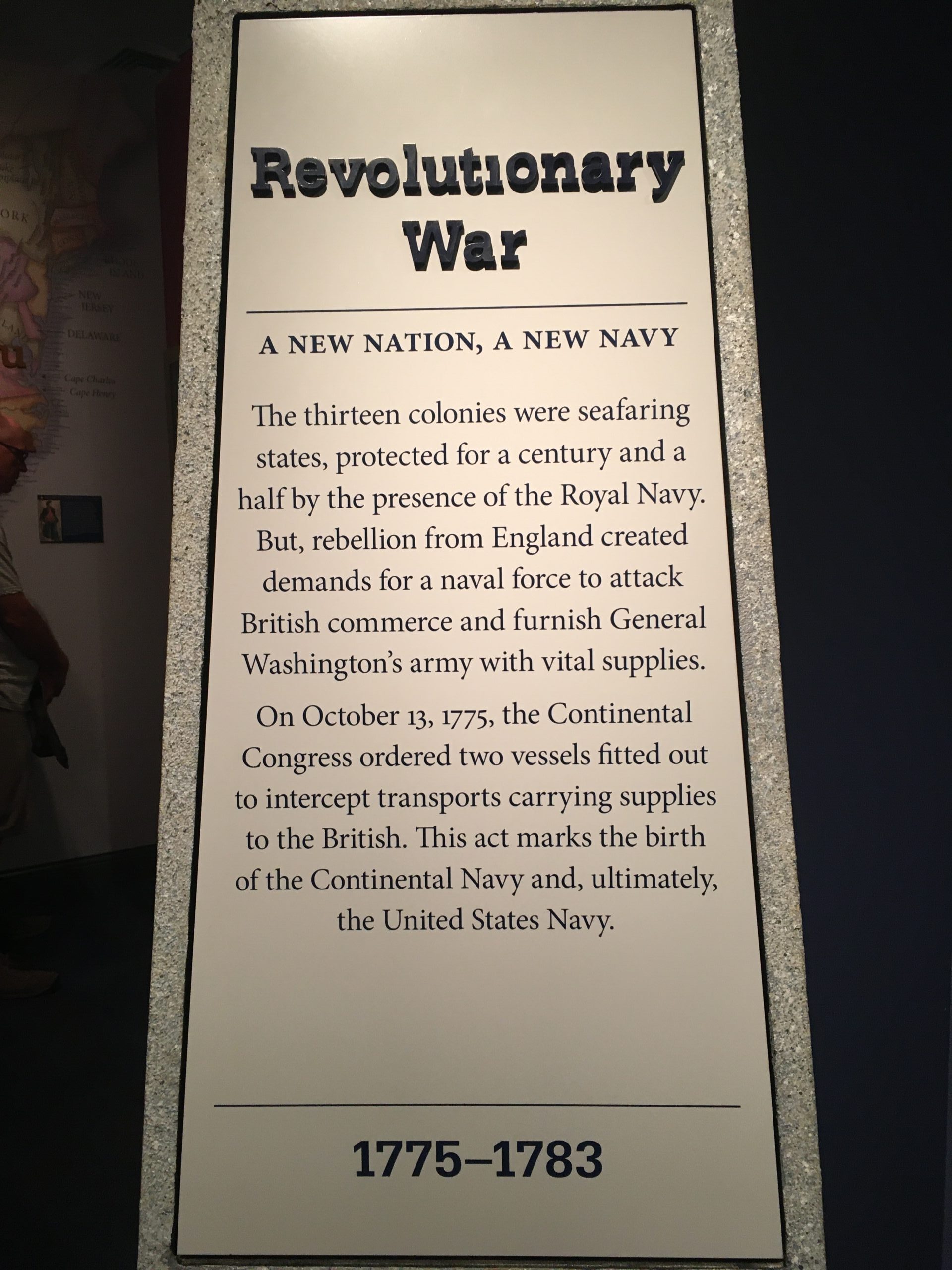

John Paul Jones is big on this campus. He’s one of those people from our history that school no longer teaches us about, despite the fact that he was extremely important to the Revolutionary War effort.

NPS believes this portrait was done around 1781

by Charles Willson Peale (yes, I spelled it right)

The National Archives website had a short blurb about him, and ended with the following:

This is a comprehensive edition of 6,000 pages of originals and 5,000 pages of transcriptions including correspondence, miscellaneous writings, ships papers, financial accounts, judicial proceedings, and other papers collected by Jones. These documents reveal much about the Continental Navy, American diplomatic relations with Europe, and the Russo-Turkish War in the Black Sea.

Holy cow!! That’s a lot of papers for one guy! Here’s a miniscule portion of information about him posted by our National Park Service and the Naval Academy:

John Paul (he added “Jones” later) was born in Kirkbean, Scotland. He attended parish school and then went to sea as an apprentice. Within four years, he captained his own trading ship, sailing between English ports and the West Indies. During the early 1770s, he was involved in a series of controversial command decisions that resulted in the deaths of two crewmembers. He fled to America. In 1775, he moved to Philadelphia under the name of John Paul Jones. There, he obtained a Continental navy appointment and captained several ships in raids against the British. In 1776, he commanded a worn-out French merchant ship, which he renamed the Bonhomme Richard (after Benjamin Franklin’s nom de plume ;Poor Richard”), against the British frigate Serapis. Jones’s refusal to accept defeat in this battle, even as his ship sank with nearly all her guns disabled, was one of the Continental navy’s most celebrated victories during the Revolution.After the Revolution, Jones lived in France, where his naval exploits gained him the reputation of a romantic, swashbuckling privateer. Despite his appointment as commander of the Russian fleet against the Turks in 1788, he continued to consider himself an American citizen. ~nps.gov

He was commissioned a lieutenant on the first American flagship, Alfred. Jones was quickly promoted to captain in 1776, and was given command of the sloop Providence. While on his first cruise aboard Providence, he destroyed British fisheries in Nova Scotia and captured sixteen prize British ships.

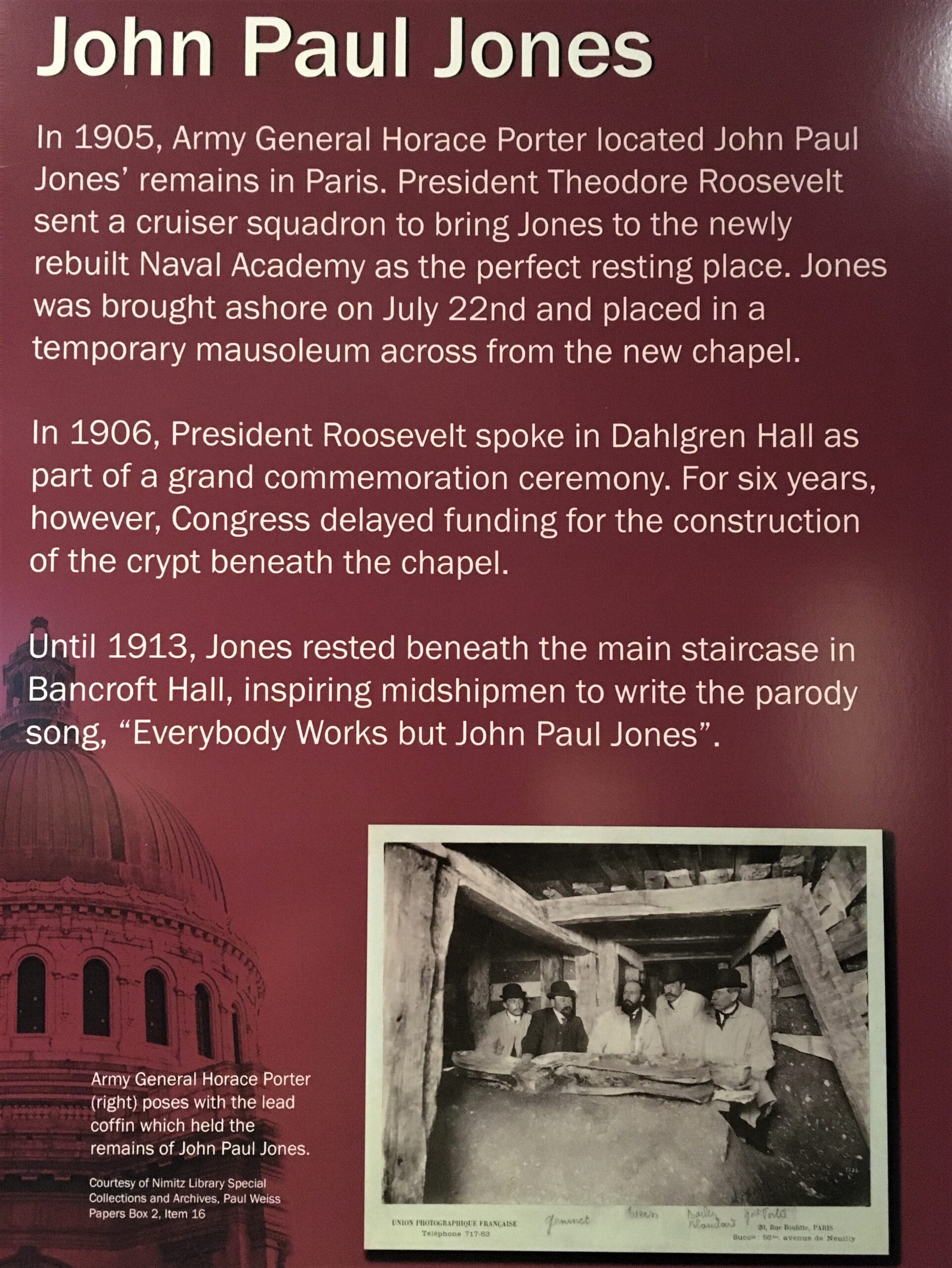

During the French Revolution, Commodore John Paul Jones, the great naval leader of the American Revolution, died in Paris at the age of 45. Lacking official status and without financial security, Jones died alone in his apartment on July 18, 1792. An admiring French friend arranged for his funeral and provided for a handsome lead coffin. John Paul Jones was buried in St. Louis Cemetery, the property of the French royal family. Four years later France’s revolutionary government sold the property and the cemetery was forgotten.

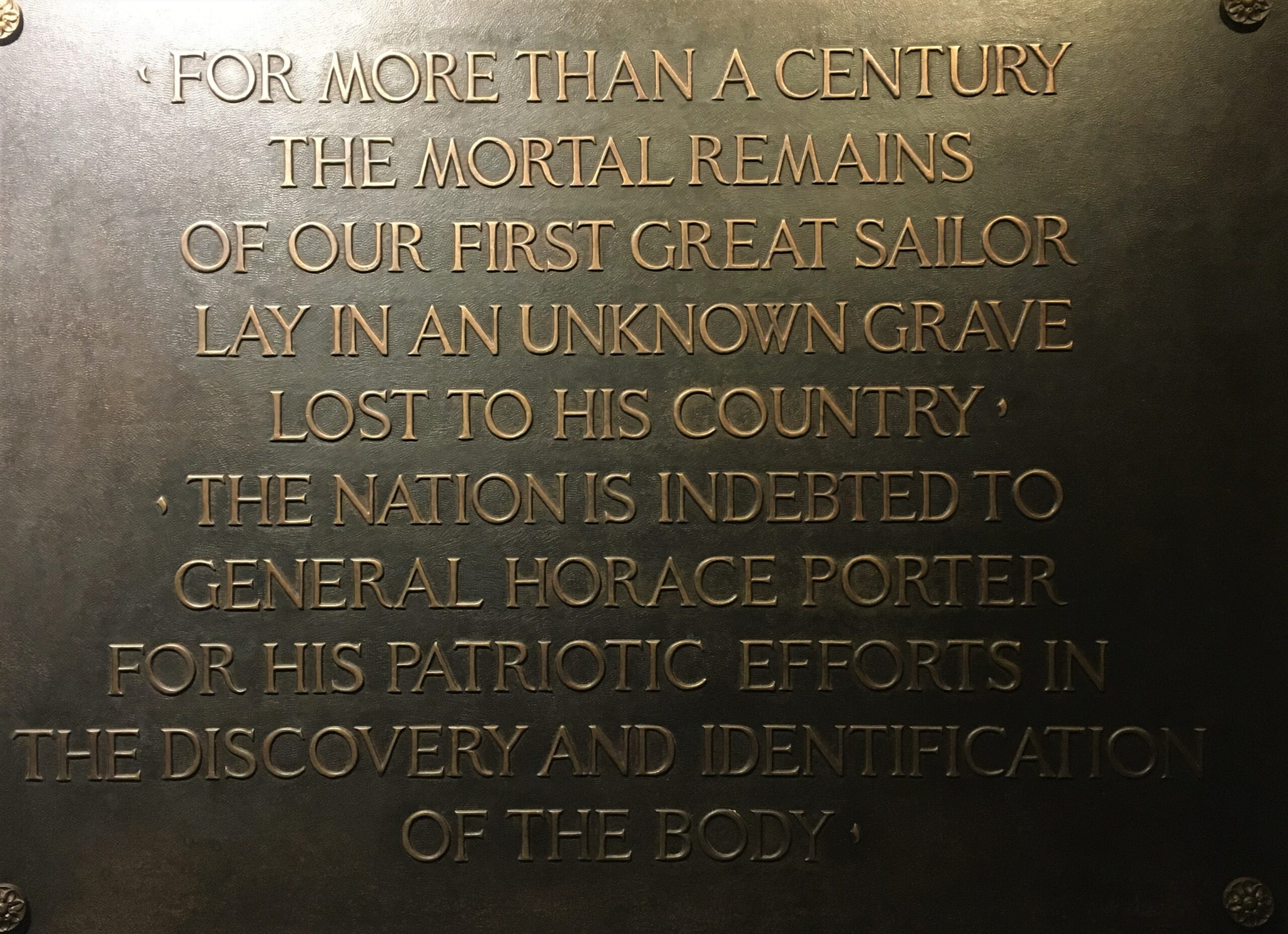

Over a century later, a search began to find the body of John Paul Jones for the purpose of returning his remains to the United States. The American Ambassador to France, General Horace Porter, personally led in the research to relocate the forgotten cemetery, provided the funds to excavate the casket and coordinated the efforts to repatriate the mortal remains of the great naval hero. Correspondence, antique maps and other records in the French national library and archives provided Ambassador Porter the information which helped in the discovery of the built-over cemetery. After weeks of tunneling through basement walls and streets, the casket of Jones was found and disinterred.

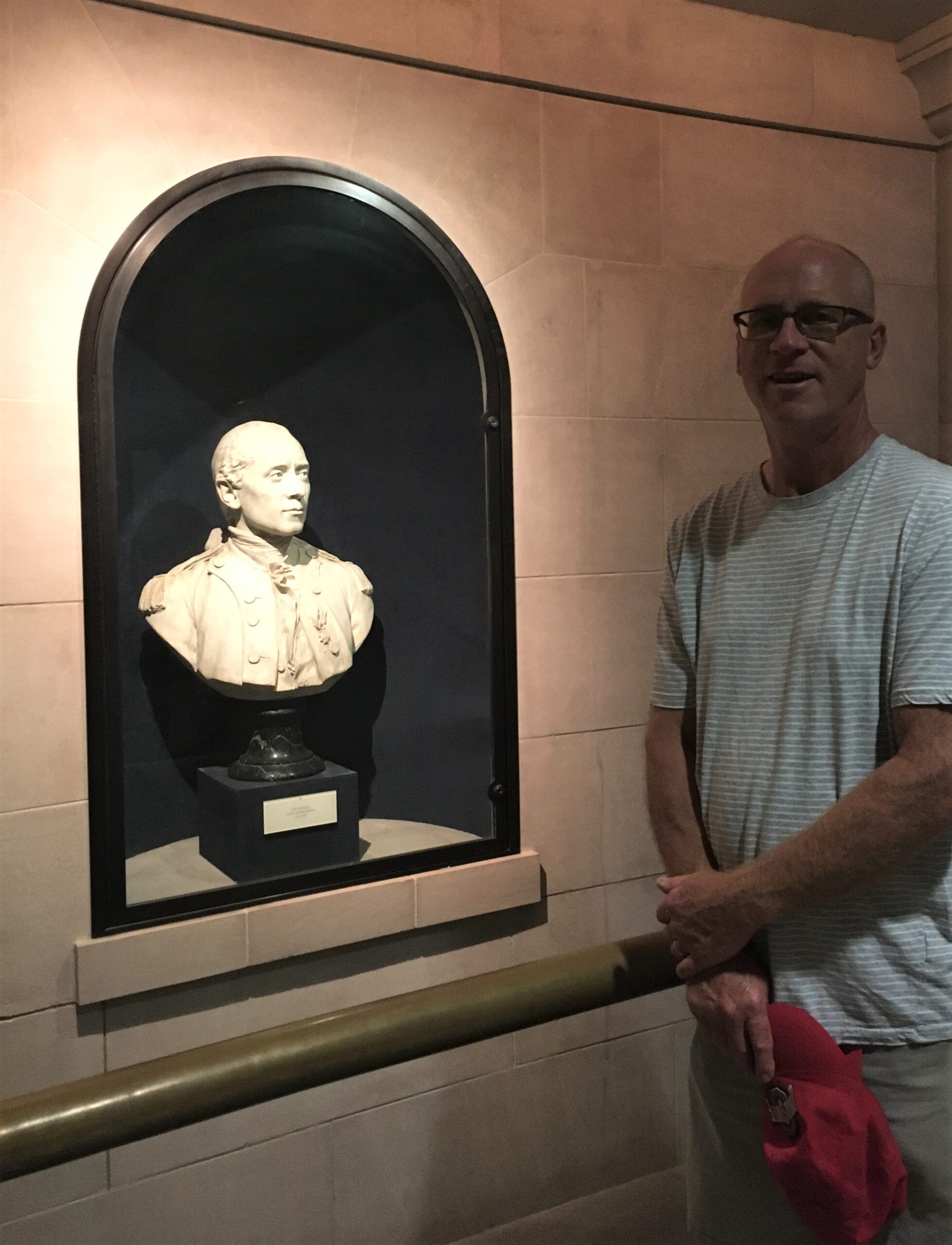

Remarkably, his corpse, which had been wrapped in a winding cloth and placed in straw and alcohol in a tightly sealed lead casket, was nearly perfectly preserved. He was taken to the University of Paris where a complete autopsy was performed. There the head of the corpse was compared to the sculptured portrait bust of Jones executed in 1780 by Jean Antoine Houdon, who had taken a plaster impression directly for his subject’s head. The autopsy and forensic study proved conclusively that the body was John Paul Jones. He had died of the kidney ailment nephritis, complicated by pneumonia.

Following an impressive parade, a religious service in Paris and a special train arranged by the French government to the port of Cherbourg, the remains of John Paul Jones were transferred to the USS Brooklyn, flagship of a special naval squadron sent by President Theodore Roosevelt to bring Jones home to his “country of fond election” and to the nation for which he immeasurably helped gain independence. On July 24, 1905, the naval tug Standish carried the casket ashore at Annapolis, Md., for placement in a temporary vault across the street from the new U.S. Naval Academy Chapel, which was under construction.

On April 24, 1906, elaborate and impressive ceremonies in commemoration of John Paul Jones were held in Dahlgren Hall, the new Naval Academy armory. Incidentally, this day was the anniversary of the battle between the Jones’s Ranger and HMS Drake, fought in the Irish Sea in 1778. It had been the first major naval battle fought under the newly adopted “starred and striped” flag and had resulted in Jones’ capture of an important warship in Great Britain’s home waters. President Roosevelt, Ambassador Porter, Admiral George Dewey and many other dignitaries attended the ceremonies. France sent an entire naval fleet up the Chesapeake Bay to mark the occasion. Afterwards the casket of John Paul Jones was placed in the Academy’s Bancroft Hall to await completion of his permanent tomb, in the new Naval Academy Chapel.

Jones was bid to rest in the crypt of the Naval Academy Chapel on Jan. 26, 1913. The crypt was designed by Beaux Arts architect Whitney Warren, and the 21-ton sarcophagus and surrounding columns of black and white Royal Pyrenees marble were the work of sculptor Sylvain Salieres. The sarcophagus is supported by bronze dolphins and is embellished with cast garlands of bronze sea plants. Inscribed in set-in brass letters around the base of the tomb are the names of the Continental Navy ships commanded by John Paul Jones during the American Revolution: Providence, Alfred, Ranger, Bonhomme Richard, Serapis, Alliance and Ariel. American national ensigns (flags) and union jacks are placed between the marble columns.

Quotes:

“An honorable Peace is and always was my first wish! I can take no delight in the effusion of human Blood; but, if this War should continue, I wish to have the most active part in it.”

“I have not yet begun to fight!”

“I wish to have no connection with any ship that does not sail fast; for I intend to go in harm’s way.”

“If fear is cultivated it will become stronger, if faith is cultivated it will achieve mastery.”

“It seems to be a law of nature, inflexible and inexorable, that those who will not risk cannot win.”

“Whoever can surprise well must conquer.” ~usna.edu

If you’d like to know more about this remarkable and important man from our history, check out:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Paul-Jones-United-States-naval-officer

here’s a picture of him. : )

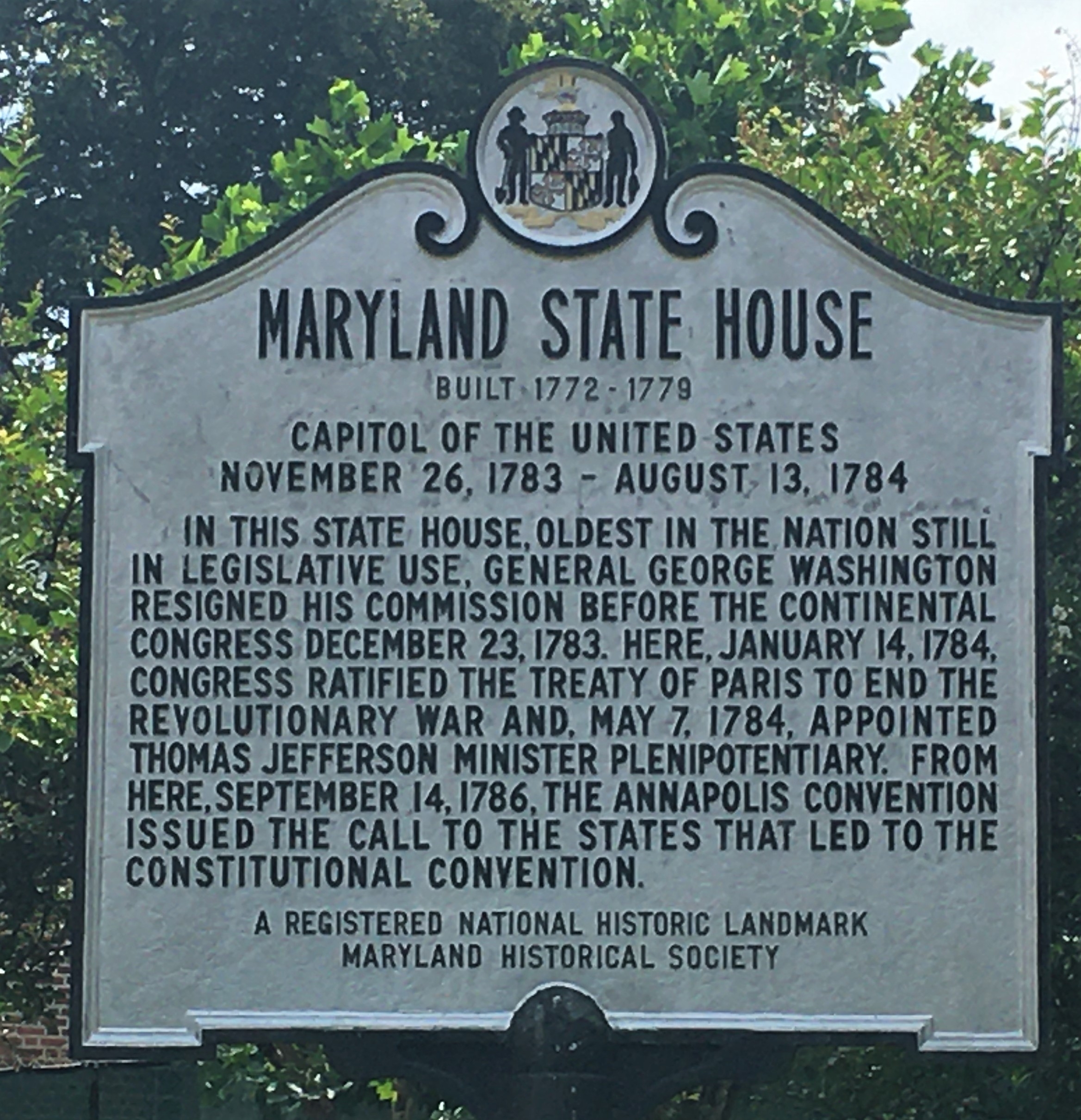

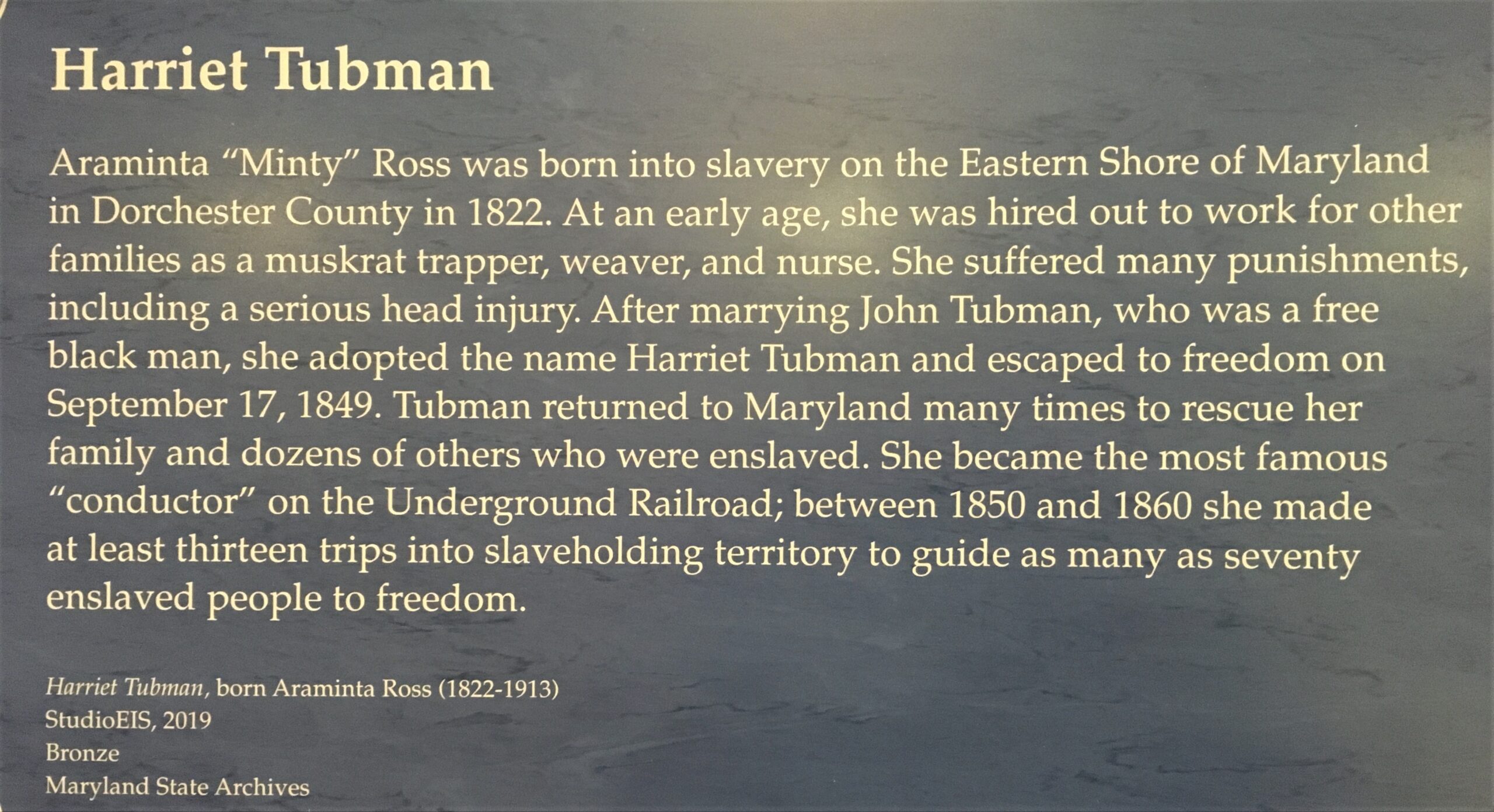

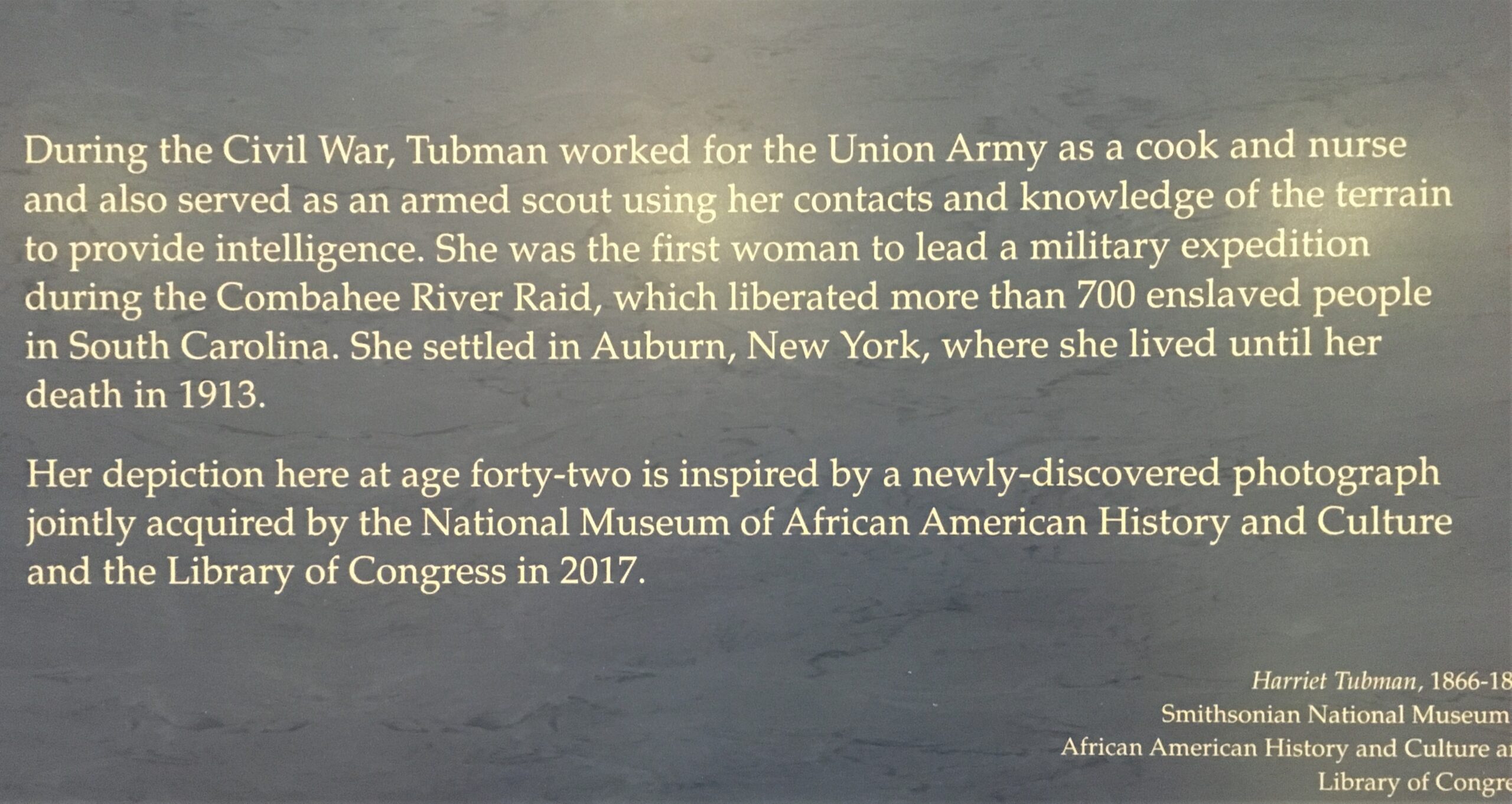

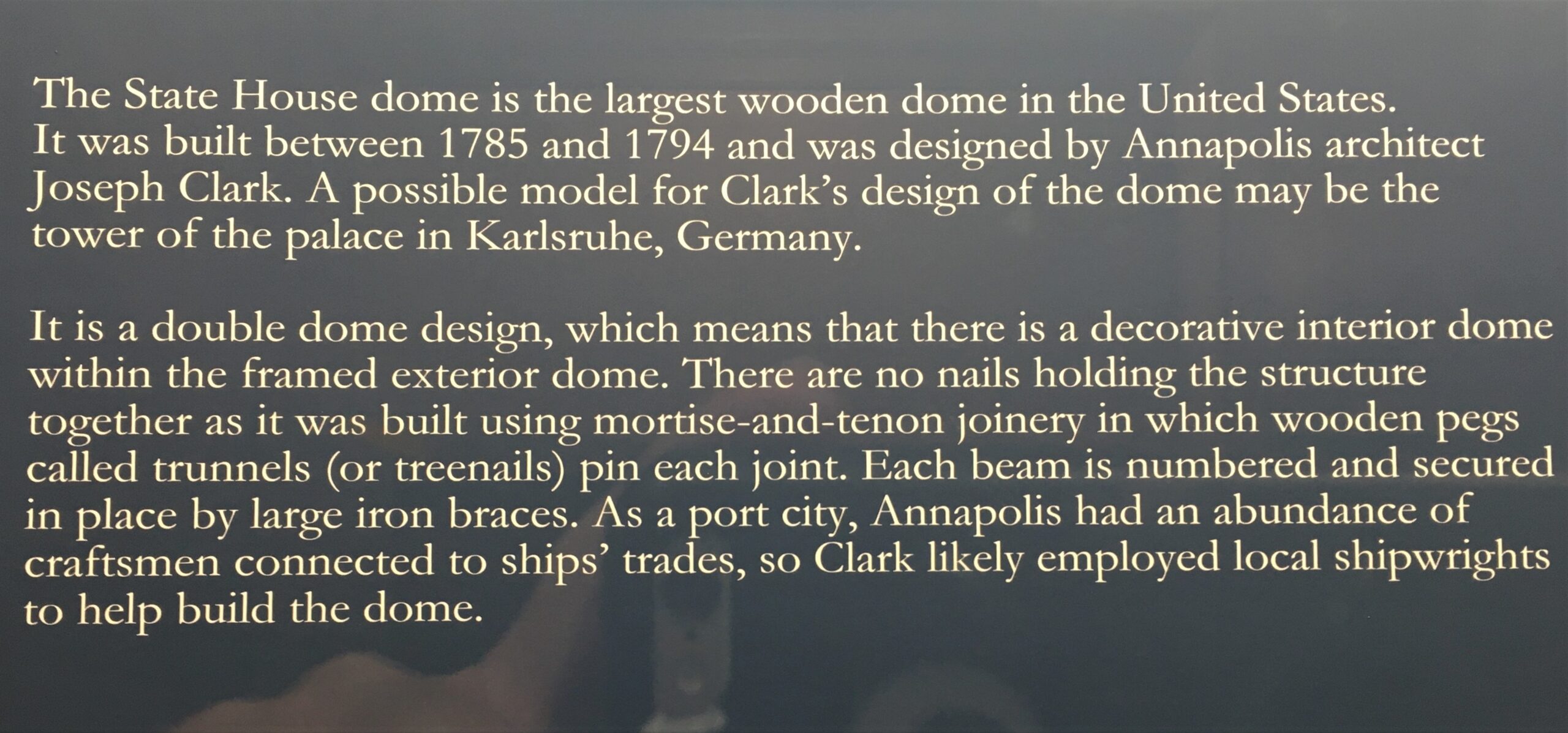

Once we completed our time at the academy, we walked through town to the State House (aka Maryland’s Capital Building). They’re working on repairs and renovations on their tower, but you can walk around inside, just like the other capital buildings we’ve been in. Most we’ve been to are quite grand, especially compared to this one. Maryland’s capital building looks more like Independence Hall. It is most notably the place where Washington resigned his military commission. And they have his actual speech in his handwriting! Read about that, and it’s importance taken from msa.maryland.gov:

George Washington’s Resignation Speech Annapolis, December 23, 1783 (One of the most important documents in American history)

Mr. President,

The great events on which my resignation depended, having at length taken place, I have now the honor of offering my sincere congratulations to Congress, and [&] of presenting myself before {Congress} them, to surrender into their hands the trust committed to me, and to claim the indulgence of retiring {request permission to retire} from the Service of my Country. Happy in the confirmation of our Independence and Sovereignty, and pleased with the opportunity afforded the United States, of becoming a respectable Nation {as well as in the contemplation of our prospect of National happiness}, I resign with satisfaction the appointment I accepted with diffidence— A diffidence in my abilities to accomplish so arduous a task, which however was superseded by a confidence in the rectitude of our Cause, the support of the supreme Power of the Union, and the patronage of Heaven. The successful termination of the War has verified the most sanguine expectations- and my gratitude for the interposition of Providence, and the assistance I have received from my Countrymen, increases with every review of the momentous Contest. While I repeat my obligations to the Army in general, I should do injustice to my own feelings not to acknowledge in this place the peculiar Services and distinguished merits of the Gentlemen who have been attached to my person during the War. —It was impossible the choice of confidential officers to compose my family should have been more fortunate. —Permit me Sir, to recommend in particular those, who have continued in service to the present moment, as worthy of the favorable notice & patronage of Congress.— I consider it an indispensable duty {duty} to close this last solemn act of my Official life, by commending the Interests of our dearest Country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the superintendance {direction} of them, to his holy keeping.— Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of Action, —and bidding an affectionate {a final} farewell to this August body, under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer {today deliver?} my Commission, and take my {ultimate} leave of all the employments of public life.

The words in italics were inserted by Washington as he contemplated his first draft of the speech. He also crossed out two important words, both relating to his leave of public office: “a final” farewell and “ultimate” leave. In doing so, Washington is keeping his option of returning to public life open. In the speech, Washington also makes a plea for Congress to pay the soldiers with whom he served and to fund the pensions of his officers, as they had been promised. This speech is regarded as the fourth most important document in American history after the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

A Revolutionary Act

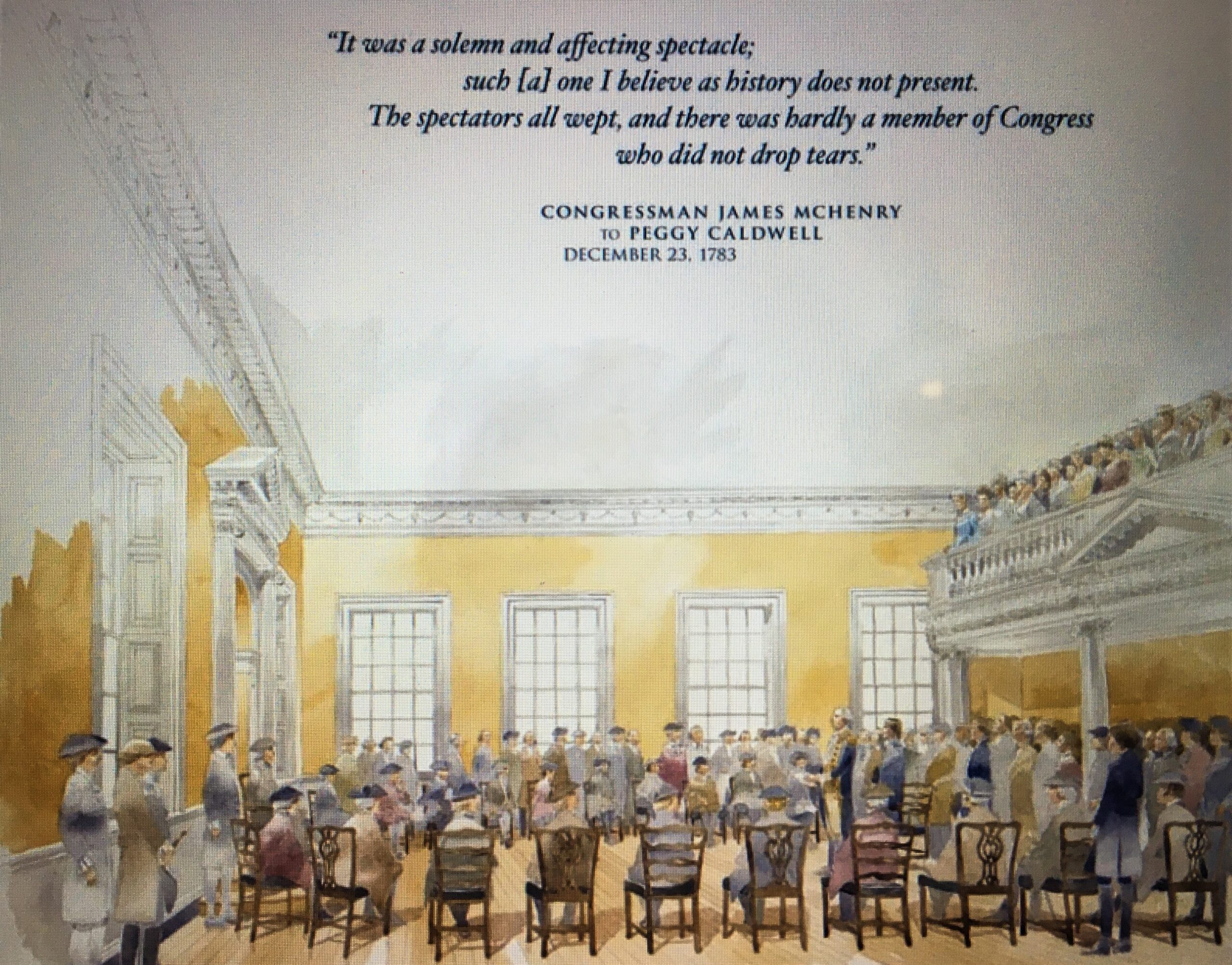

In many ways, George Washington’s resignation as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army was the final revolutionary act of the American Revolution. Many, especially in Europe, had expected that he would assume power and lead the new nation into the early stages of its independence. The Articles of Confederation of 1781 created only a loose alliance of the thirteen states. Congress was weak, and there was no obvious leader waiting in the wings. But Washington had confidence in the ability of Congress to guide the nation successfully. It was a revolutionary act of faith and a remarkable milestone in the history of our nation. By surrendering his power to the civilian authority, Washington ensured that the United States would become a republic rather than a monarchy or a nation led by the military. Most importantly, this act established the bedrock principle of American democracy: that the military is subject to civilian authority. Before he delivered his resignation speech to Congress, then meeting in the Old Senate Chamber, on December 23, 1783 Washington made clear his intent to retire in letters to friends and colleagues. On December 10, he wrote to his former aide, James McHenry, telling him of his plan to travel to Annapolis, where Congress was meeting, to “get translated into a private citizen.” Washington longed to return to Mount Vernon and his family and his life as a farmer. When Washington arrived in Annapolis on December 19, he wrote to Congress to ask how they wanted him to present his resignation. They responded with a request for him to make a brief speech at noon on December 23. While staying at Mann’s Tavern on what is now Main Street in Annapolis, Washington set to work composing this speech. At noon on December 23, 1783, Washington entered the Old Senate Chamber to deliver his brief but emotional speech of resignation. The protocol for the event had been carefully worked out by a committee of Congress that included James McHenry, Thomas Jefferson, and Elbridge Gerry. The members of Congress remained seated and “covered” (kept their hats on) while Washington stood before them facing the president of Congress, Thomas Mifflin.

At the conclusion of his remarks, Washington bowed to Congress and briefly left the room. He then returned to bid farewell to the many people who had crowded the room for the event. In addition to the members of Congress, the audience included several of the generals and other officers with whom he had served during the war, local officials, and prominent residents of Annapolis. The women in attendance were not allowed to be present on the Old Senate Chamber floor and had to watch from the “Ladies Balcony” at the back of the room. One of these women, Molly Ridout, wrote one of the very few descriptions of the ceremony in a letter to her mother: “the General seemed so much affected himself that everybody felt for him, he addressed Congress in a short Speech but very affecting many tears were shed… I think the World never produced a greater man & very few so good.” As he departed, hoping to be at Mount Vernon in time for Christmas, Washington handed his personal copy of the speech to James McHenry. It remained in the McHenry family until 2007 when it was purchased by the Friends of the Maryland State Archives. The purchase also included the letter that James McHenry wrote to his future wife, Margaret (Peggy) Caldwell, describing the ceremony. Both of these documents had been privately held since 1783.

There are two official copies of General Washington’s resignation speech: one in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. and one at the Library of Congress.

The one on display in the State House is the one from which Washington read as he addressed Congress and contains the changes he made as he composed the speech, some of which provide important clues to his thinking about his role in the nation’s future.

We skipped lunch today in order to partake of a mid-day dinner at Ziki Japanese Steakhouse, where we stuffed ourselves with the BEST sushi we’ve ever had, and hibachi dinners as well. Most excellent! And being as how it was mid-afternoon, we had a private grill. 😊

It was basically a California roll, but also wrapped in smoked salmon.

Delicious!!

and our chef made “Choo-choo” sounds. lol

Our overnight was at the Holiday Inn Express in Annapolis. Very nice and extremely clean place! The room had free HBO, so we watched one of the Jurassic Park movies before turning in for the night. Free delicious breakfast in the morning, too!

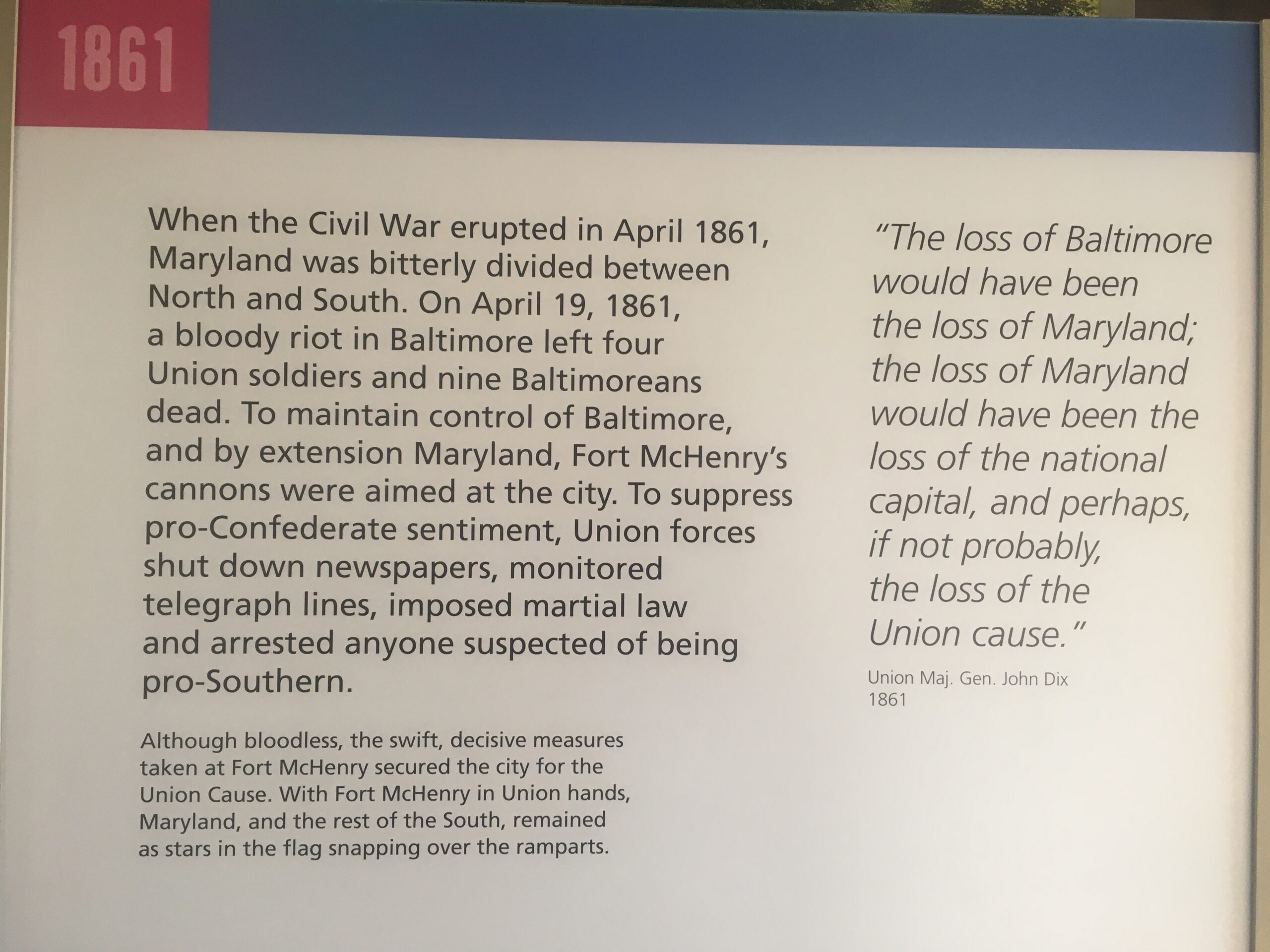

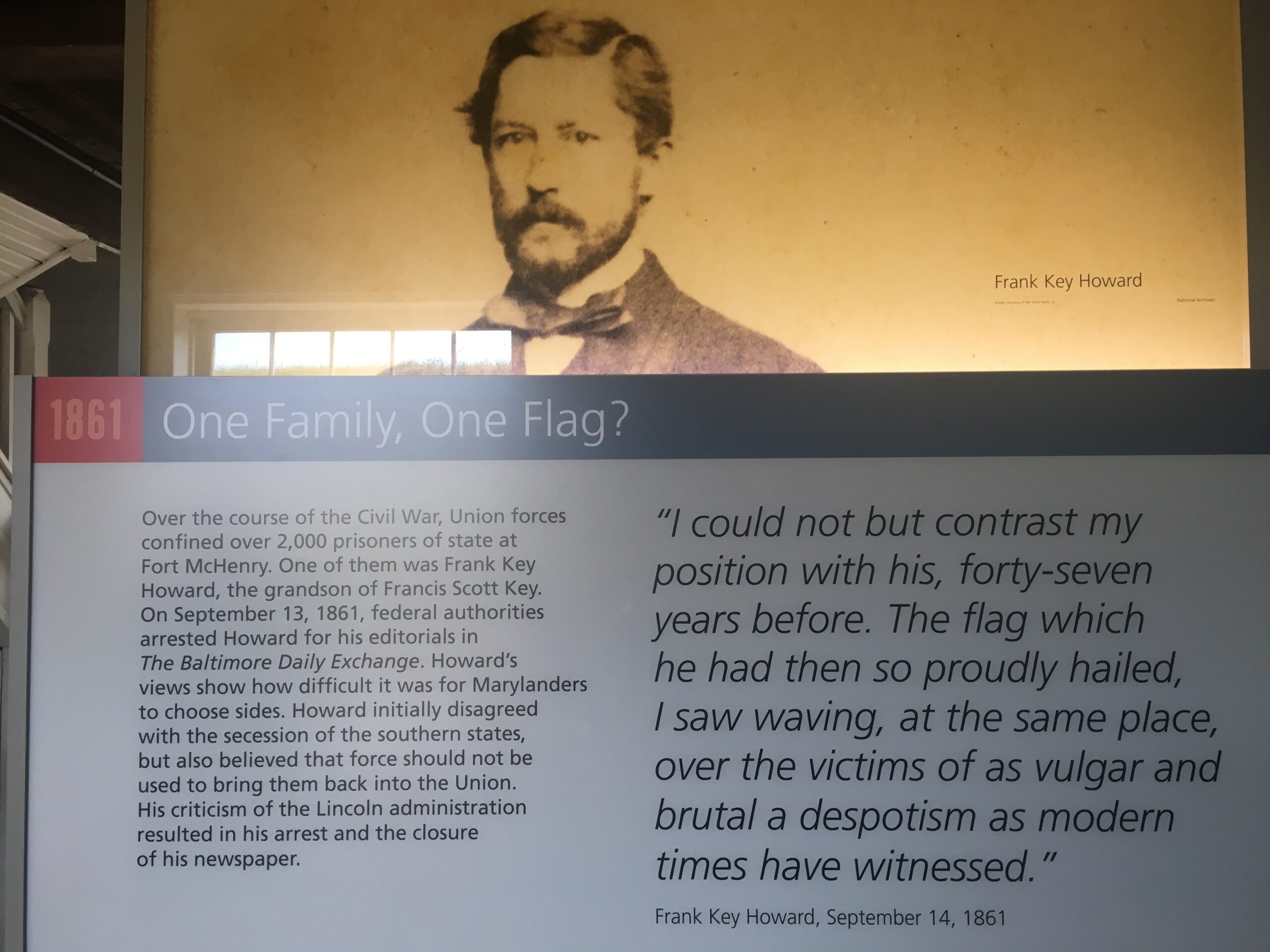

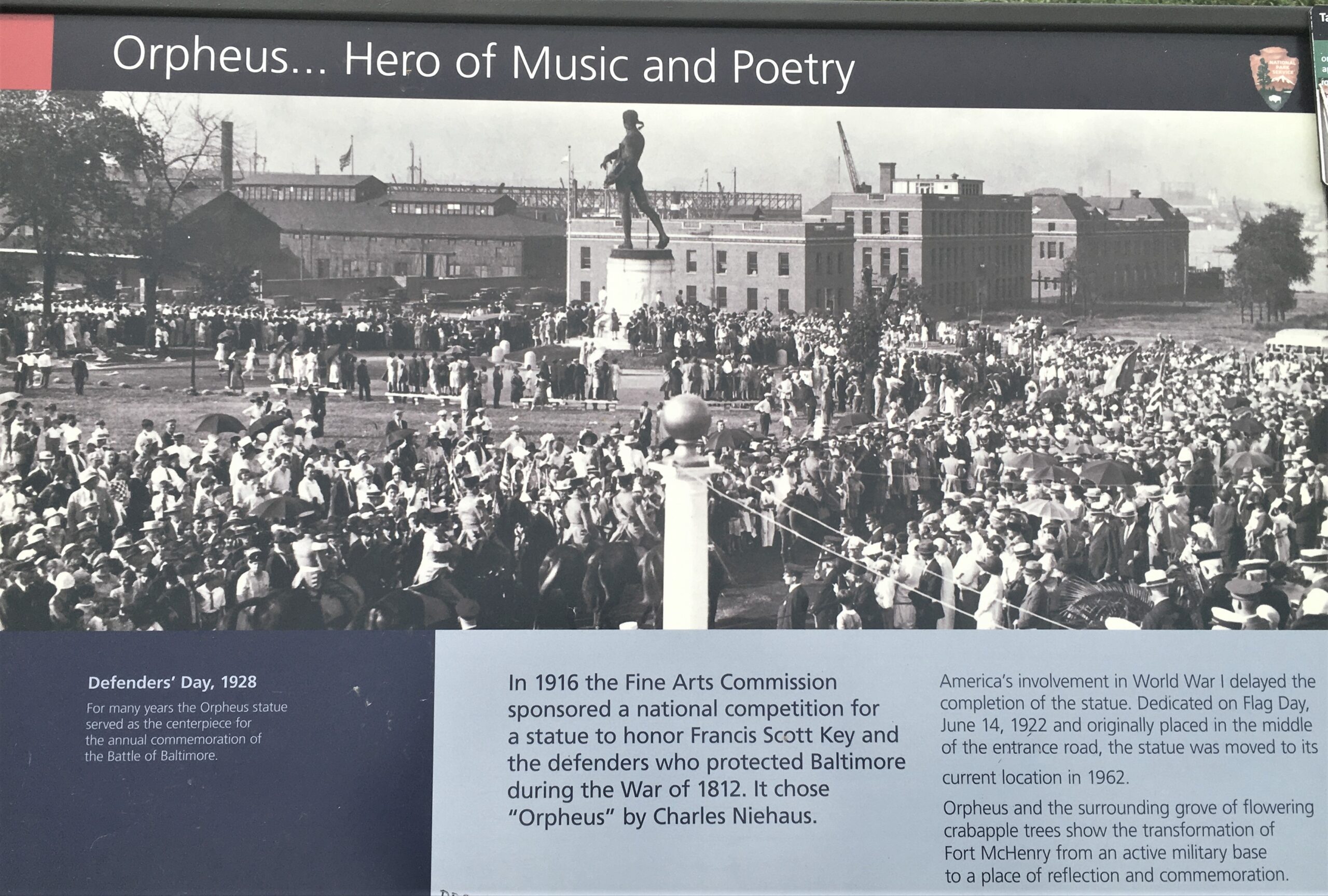

The next day, our plan was to take in Fort McHenry and the Inner Harbor in Baltimore, ending the day with a scrumptious seafood dinner at Phillip’s. Blaine’s maternal step-grandmother, Bonnie used to take us there all the time. She knew the piano player, Scott, so we’d listen to him for a while before or after dinner. Nice memories!

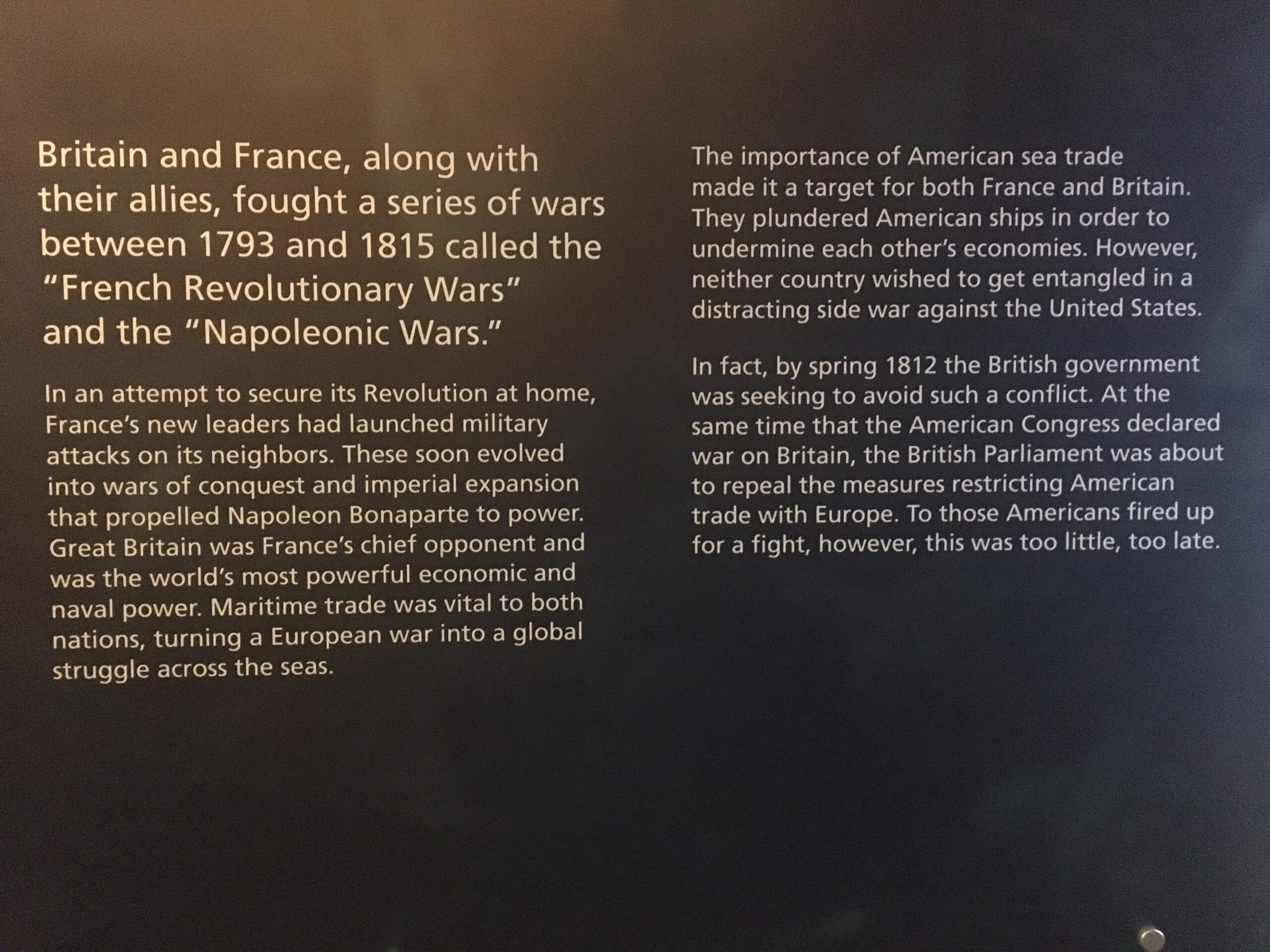

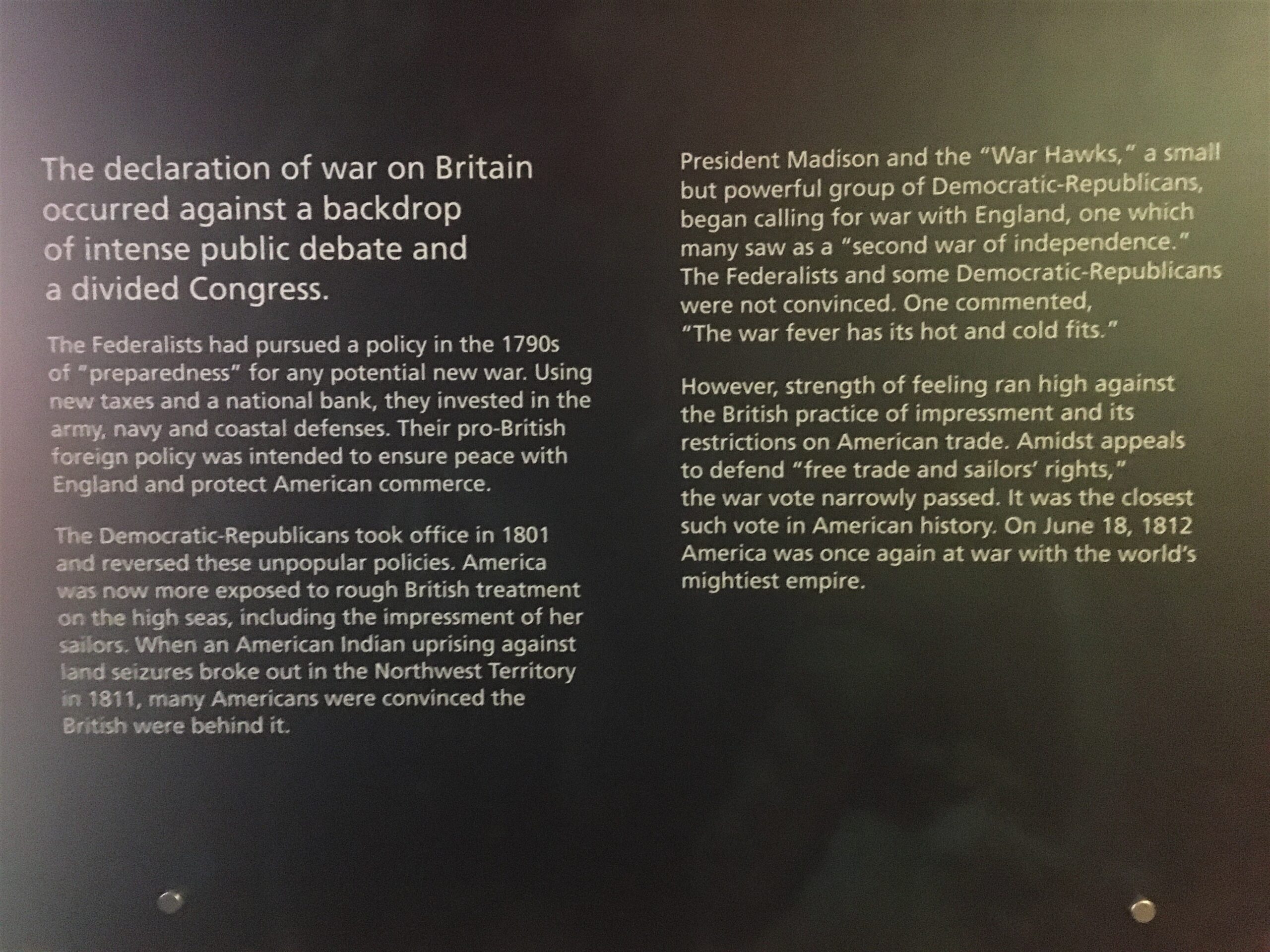

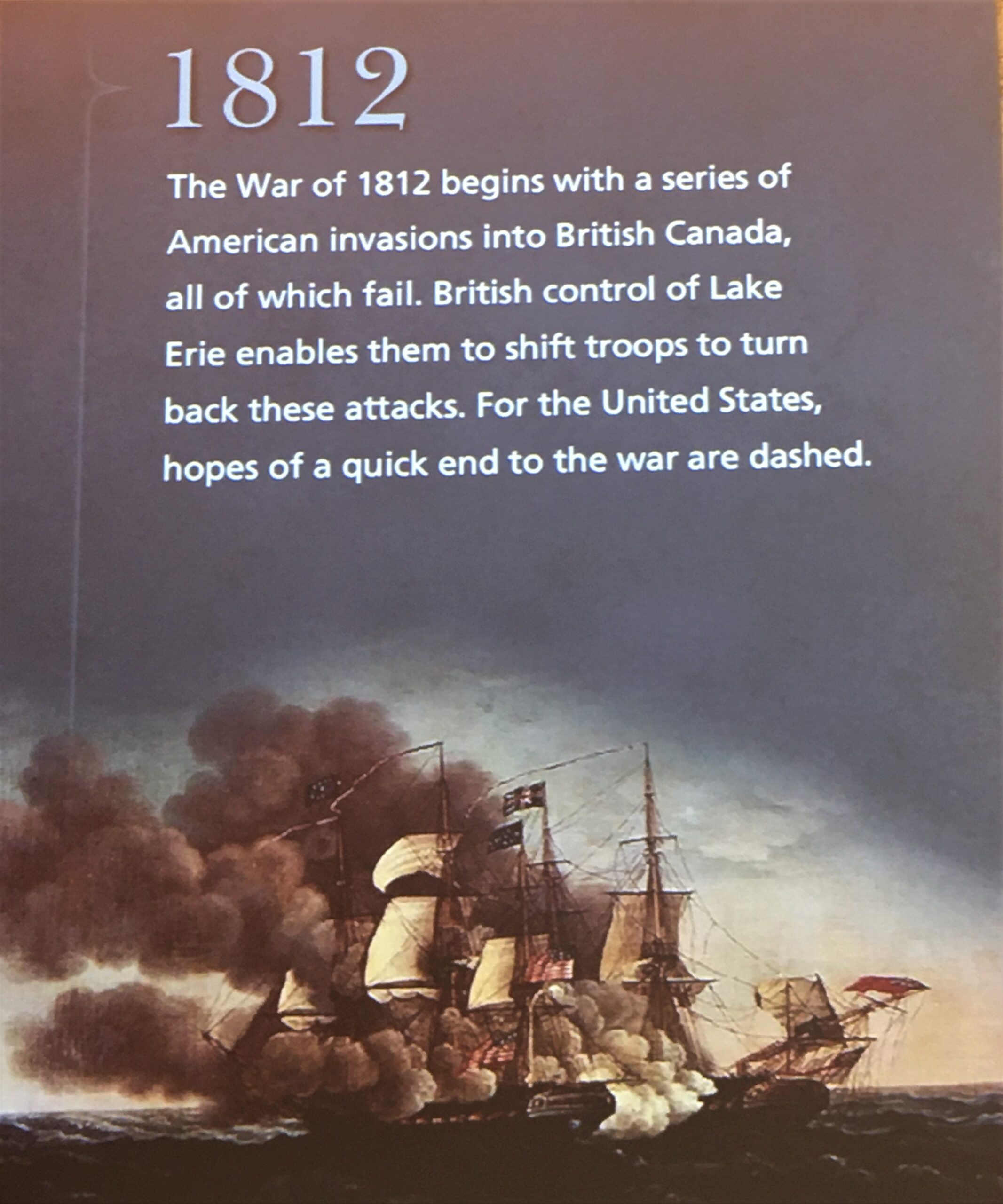

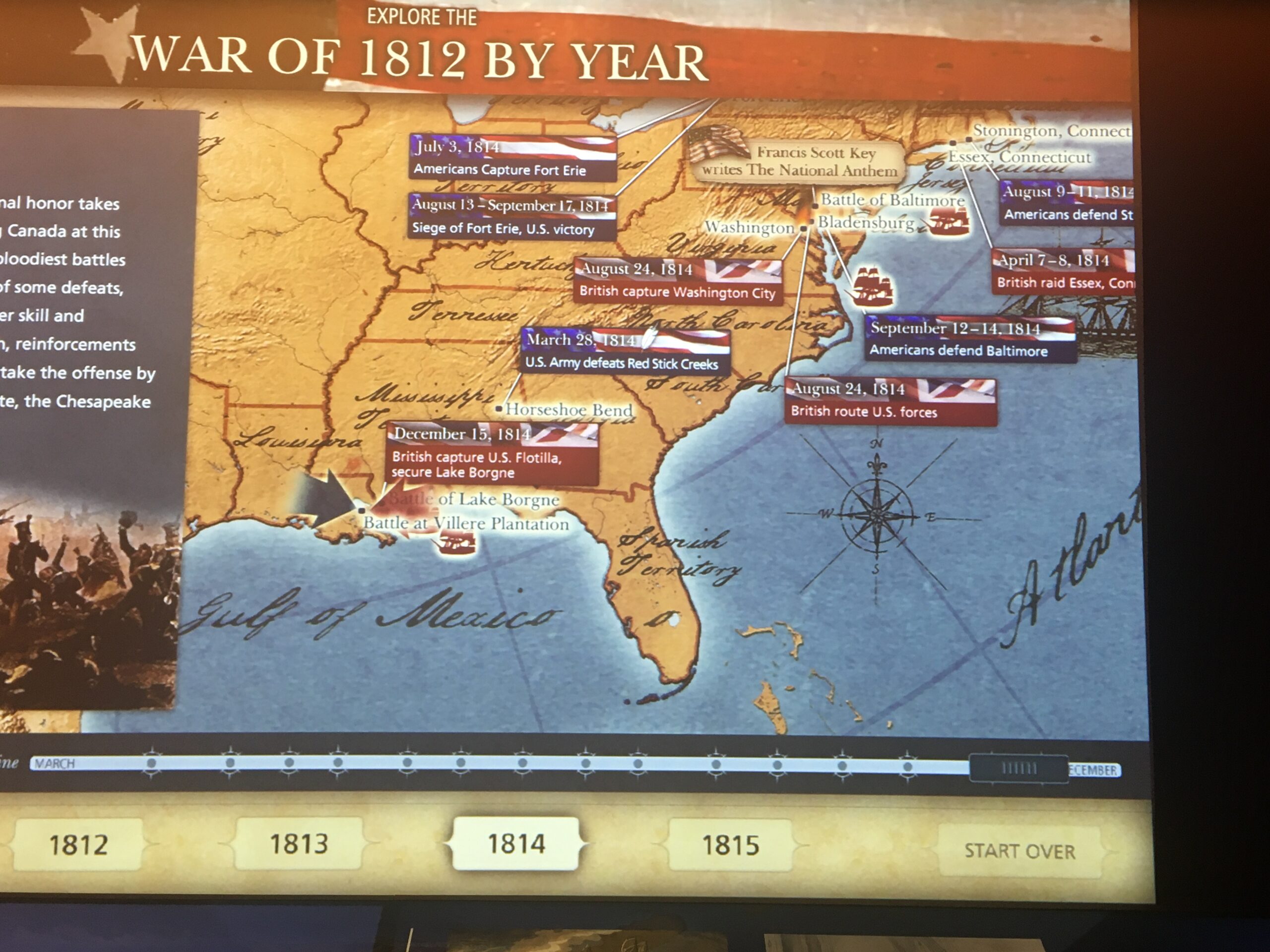

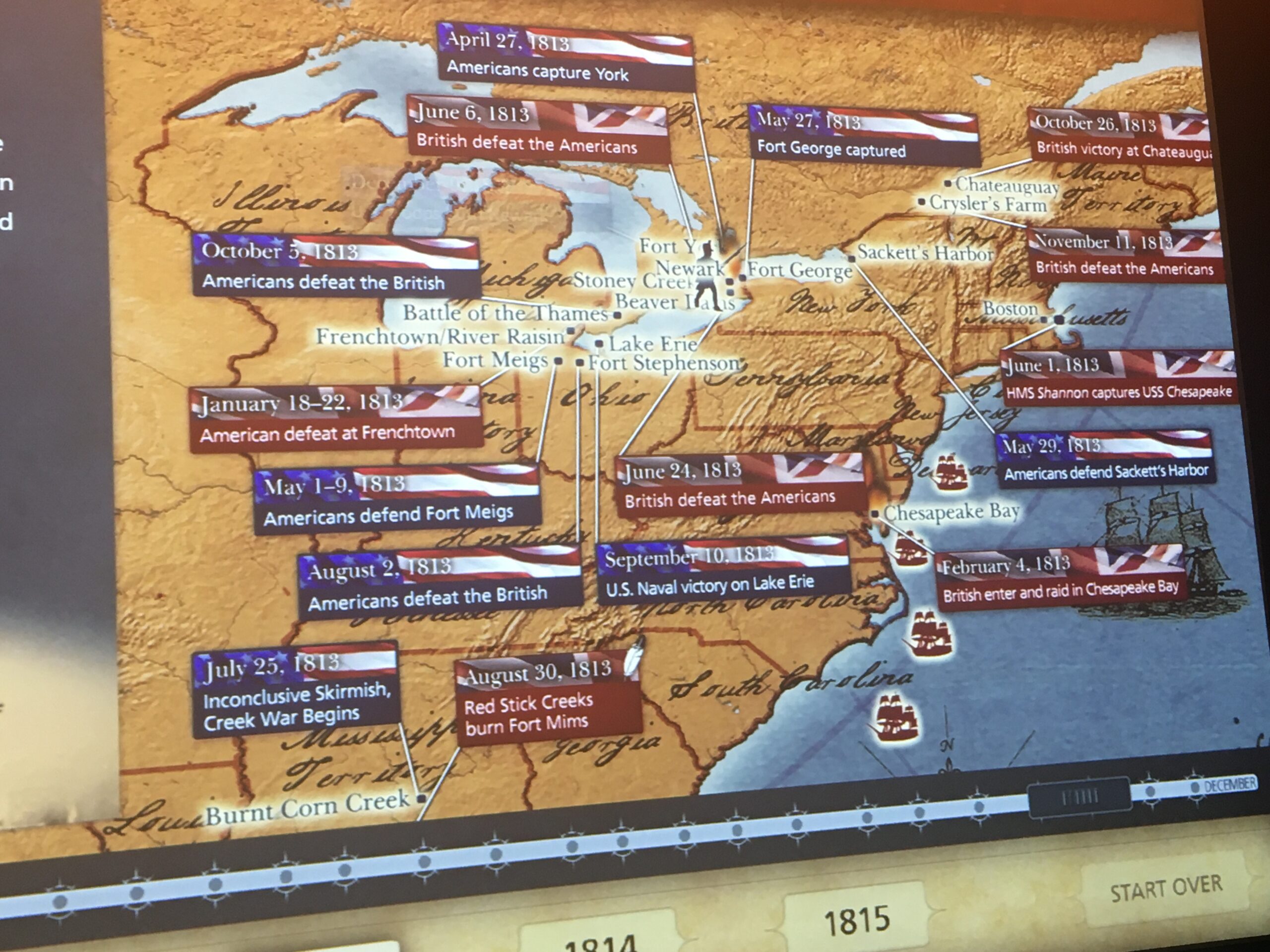

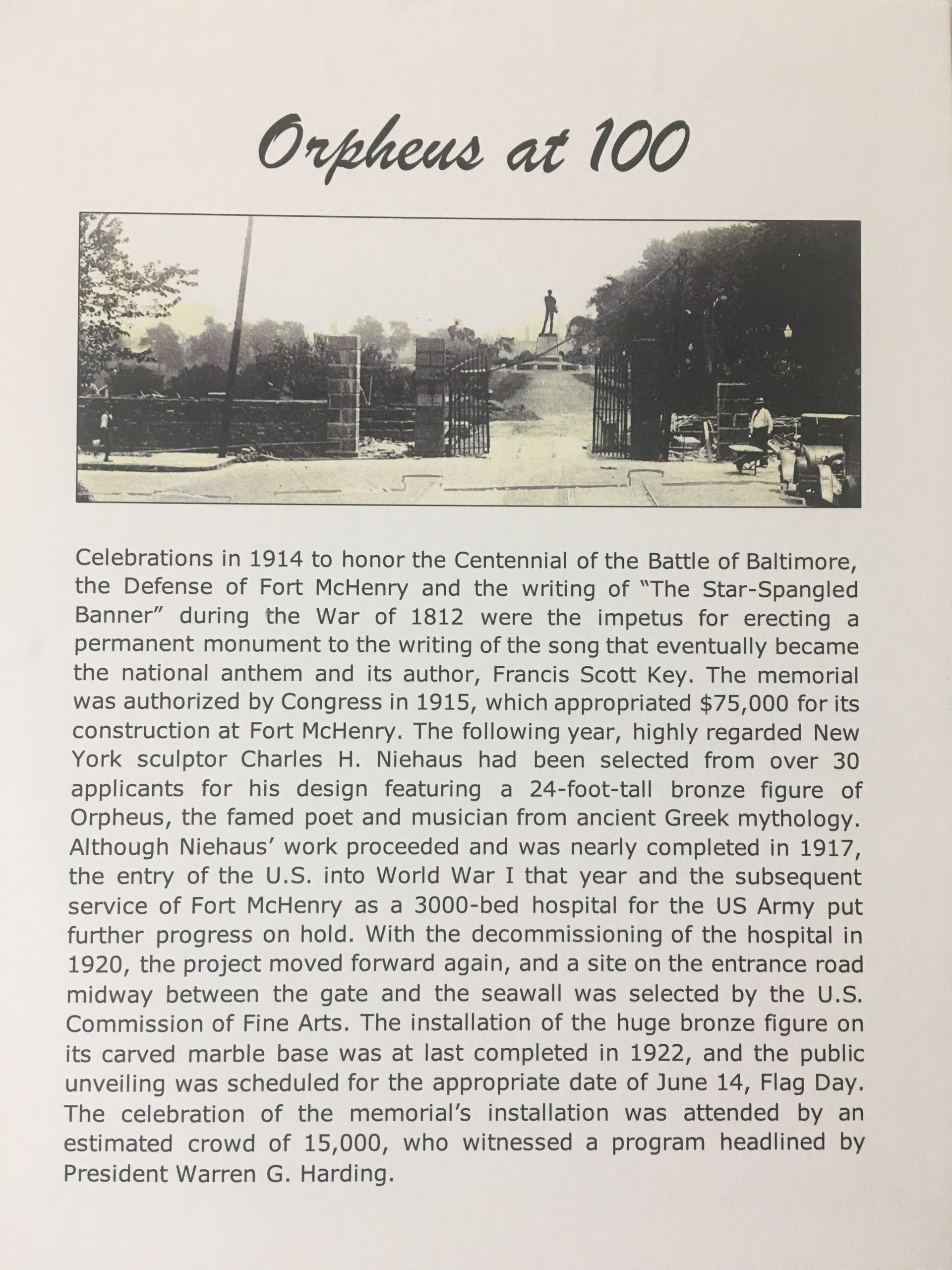

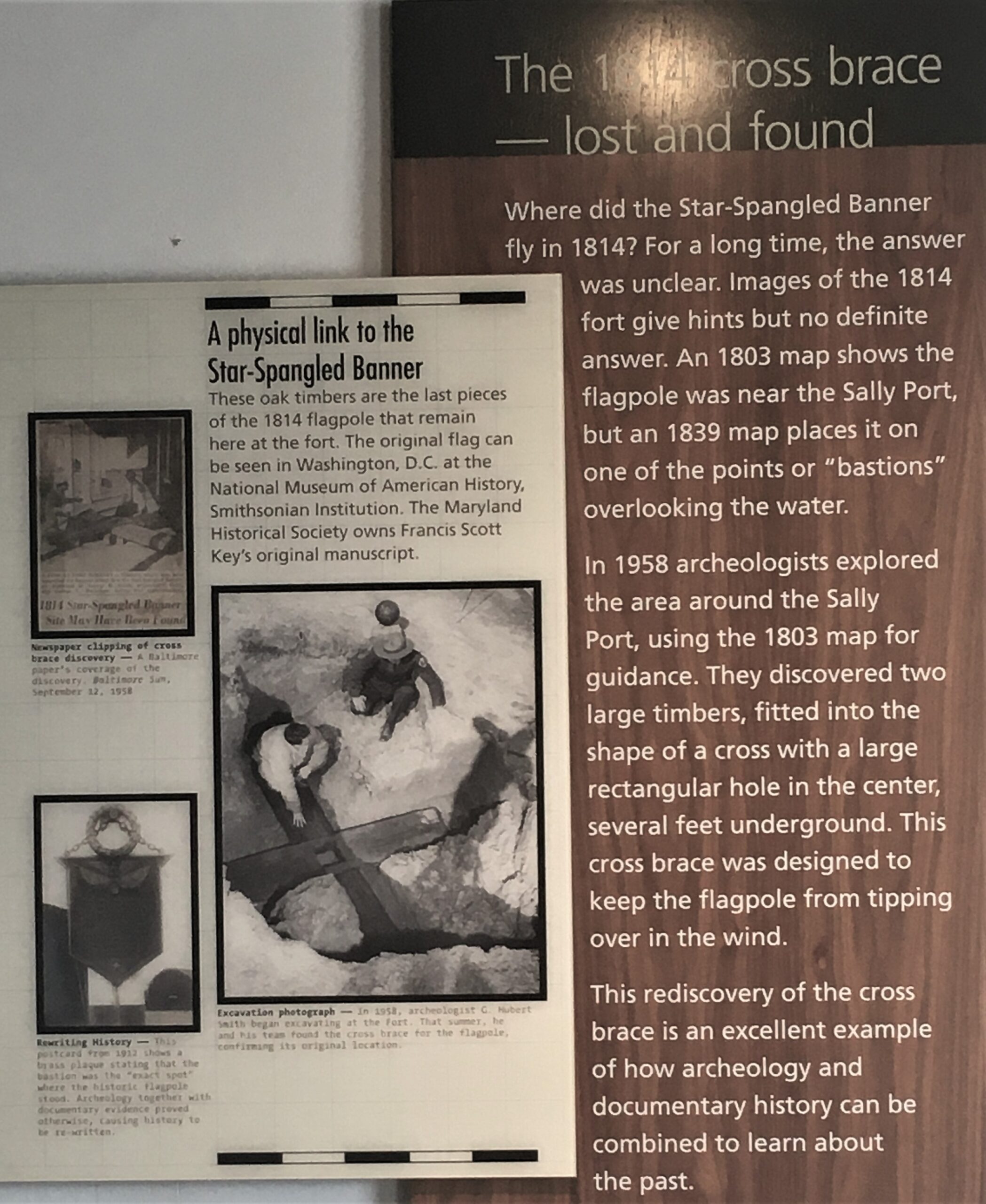

Fort McHenry’s main claim to fame is that this is where the tide of the Revolutionary War began to turn in our favor. There was a tremendous land/sea battle fought here and as men at the fort blasted towards the British ships. Oh here, let me just allow our National Park Service explain a small portion it:

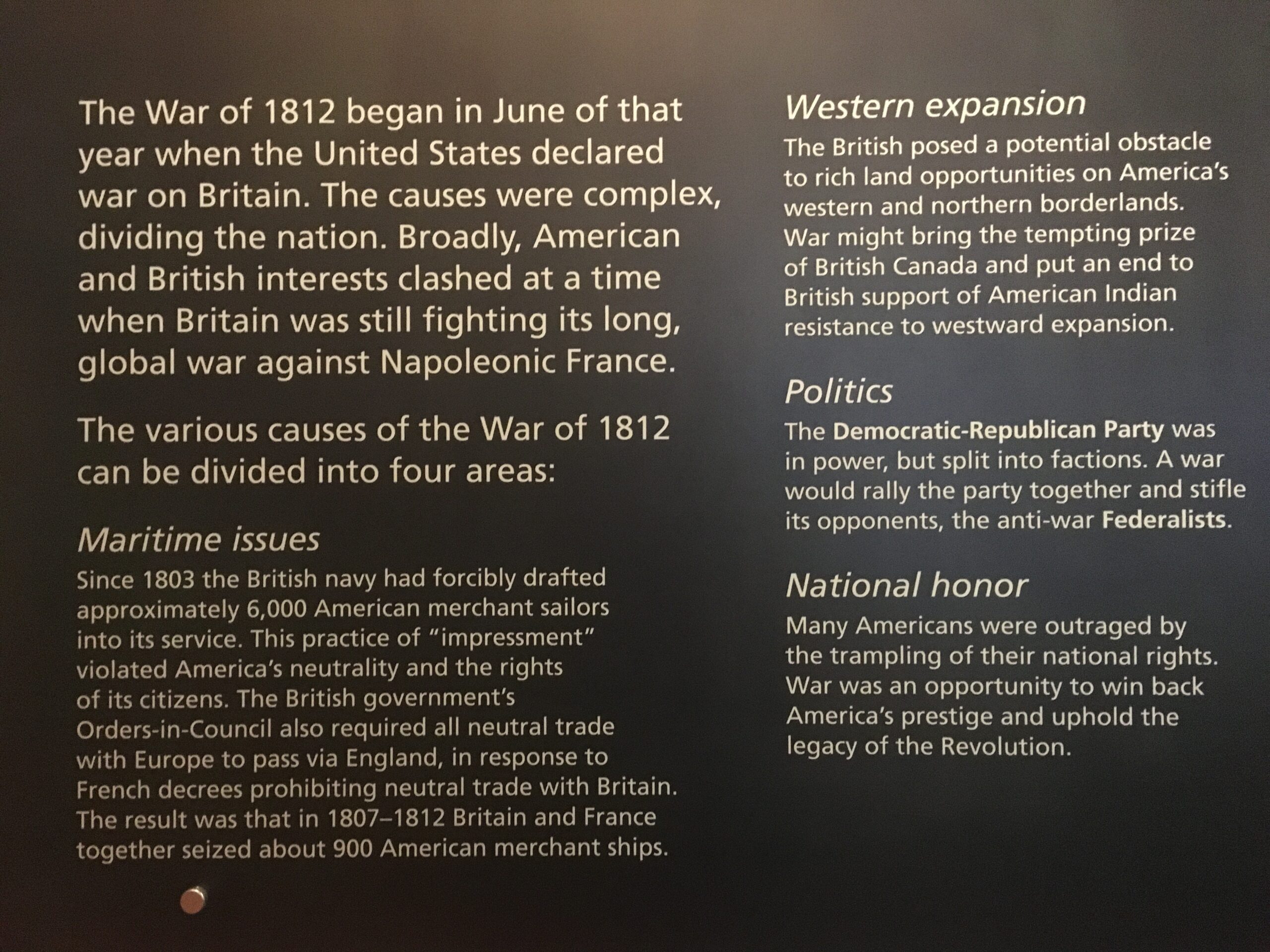

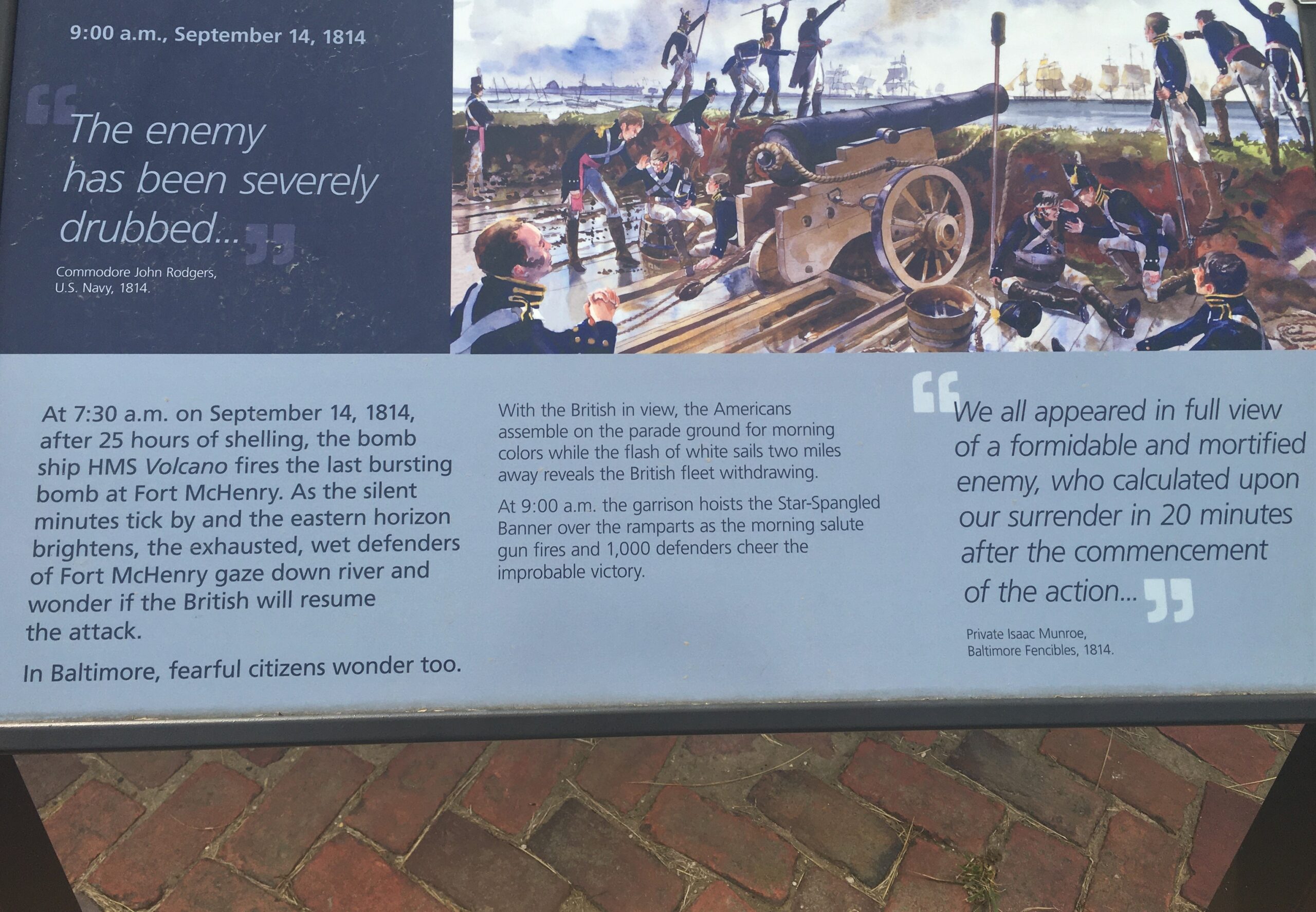

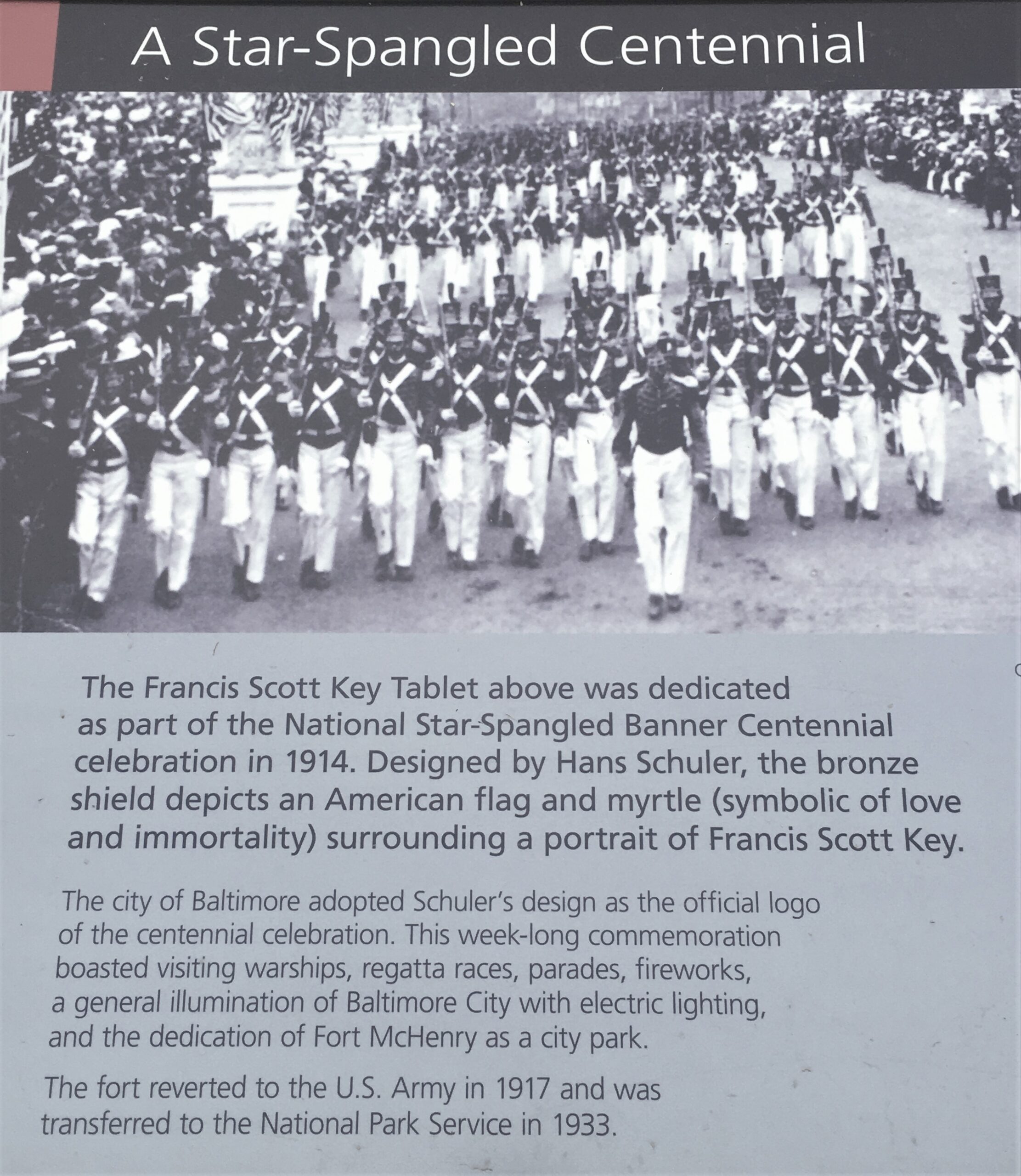

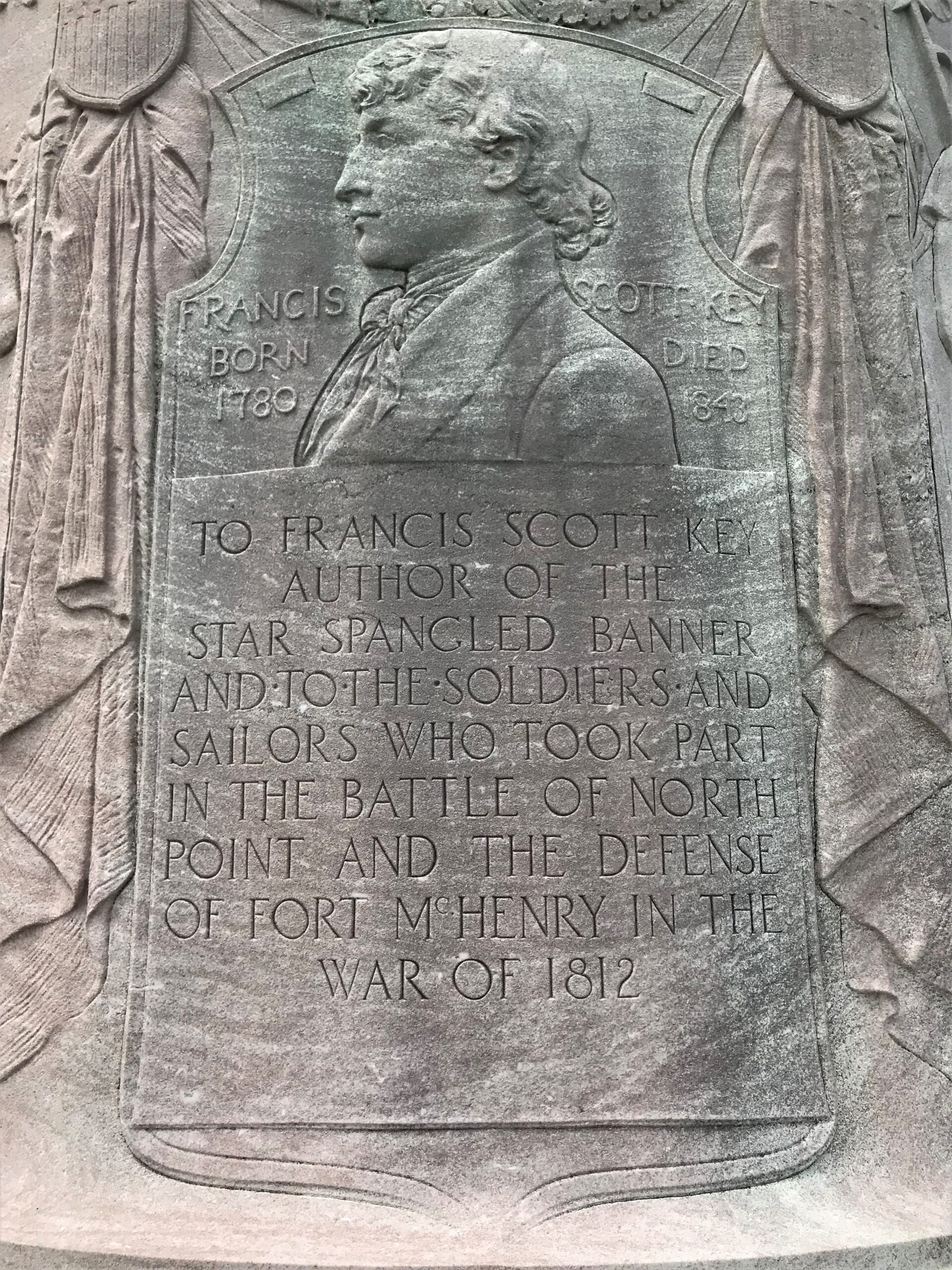

The Battle of Baltimore, fought September 12-14, 1814, was the defining moment in the War of 1812. Following their devastating victory at Bladensburg the British forces burned the American capitol, Washington D.C. Riding on the shoulders of their success, British commanders now had their eyes set on the third largest city in the United States, the port city of Baltimore. The Battle of Baltimore that would follow combined a naval and land assault against American forces around the city. Faced against the greatest military in the world, American forces held their ground and saved Baltimore from facing the same fate as Washington D.C., the epic event also inspired Francis Scott Key to write the words that would eventually become “The Star-Spangled Banner,” today’s National Anthem.

When the bombing of Fort McHenry finally stopped early on the morning of September 15, 1814, not everyone knew what the outcome was. Three miles from the fort, the truce ship, the PRESIDENT, was still tethered to Cochrane’s temporary command ship, the HMS SURPRIZE . Francis Scott Key, John Skinner, and Dr. Beanes had watched the attack from the deck of the PRESIDENT, and once the firing had stopped they waited for it to resume. When it did not the Americans were trying to figure out why the British had stopped firing. What did it mean? Had the fort and the city surrendered?

For nearly 90 minutes the Americans on the truce ship were waiting anxiously for an answer. They could tell the British ships were preparing to sail. But sail to where? Back down the Patapsco towards the fleet, or up the Patapsco into the city?

Key and Skinner kept looking through a spyglass to see if a flag was still on the pole and if so, whose flag was it? Was it the same one that they had seen the night before? Inside the fort the men of the garrison were also wondering what the British cease fire meant. The men on the ramparts kept a sharp eye on the ships, ready to open fire if they started towards the city.

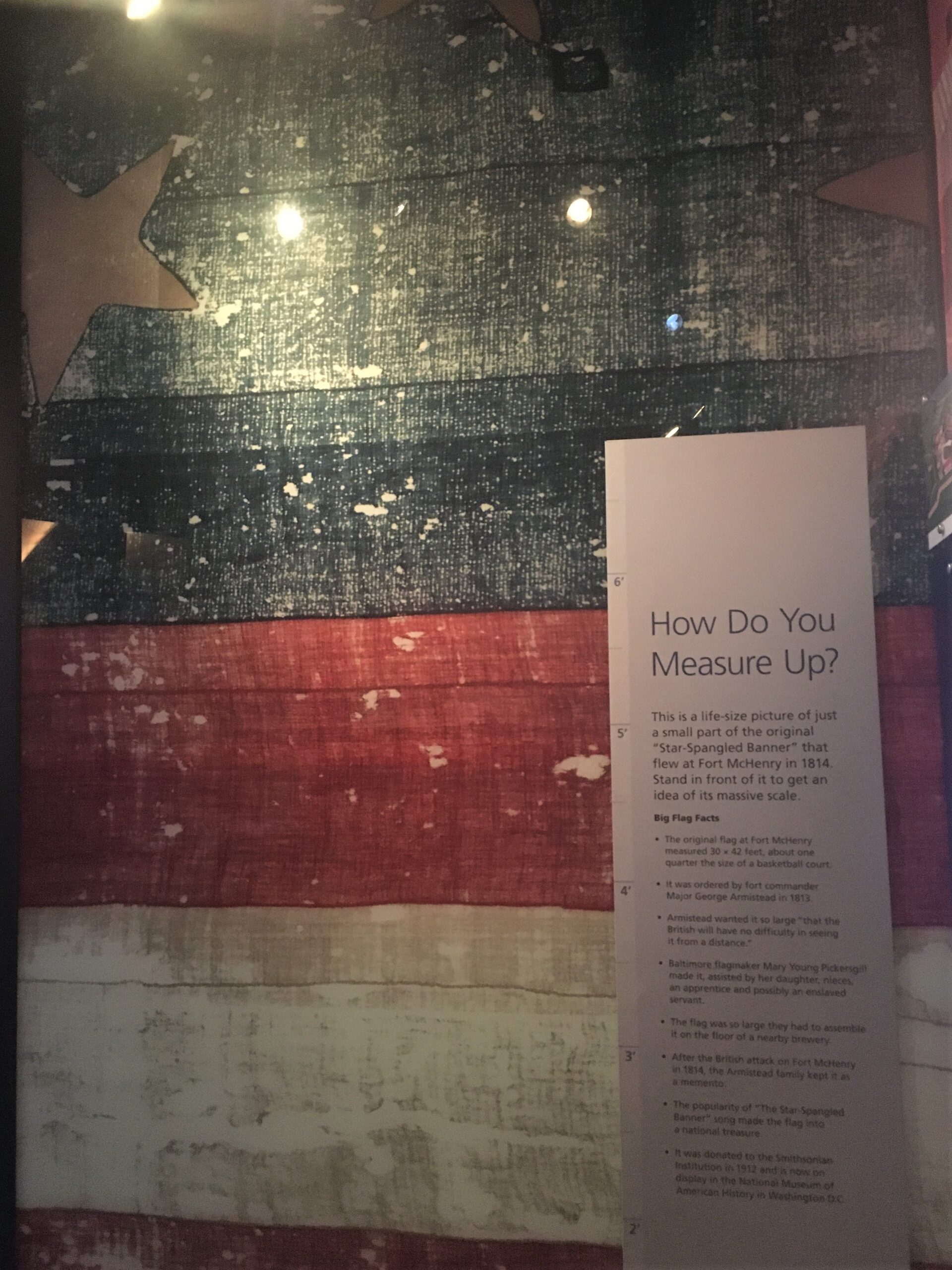

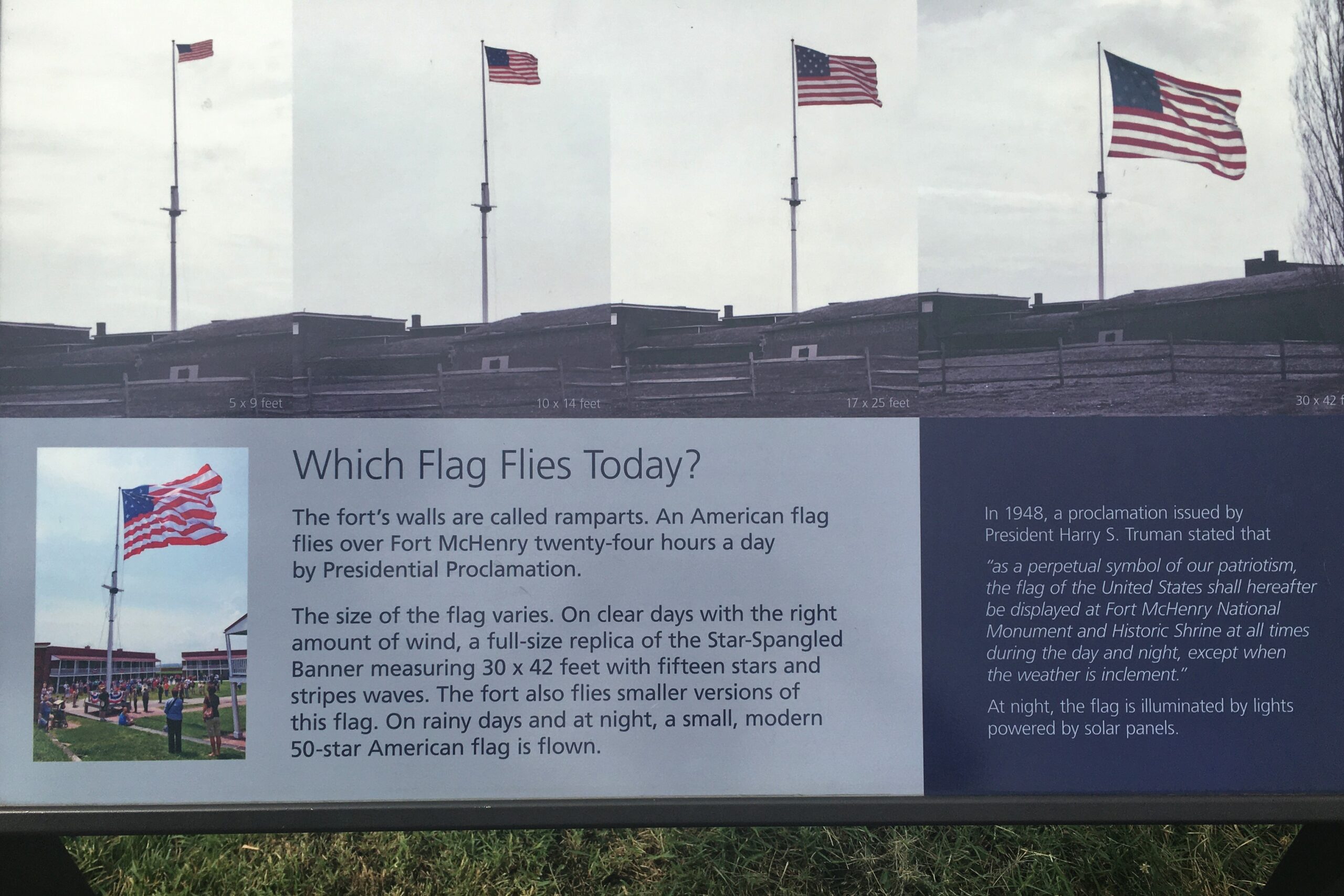

Major Armistead was receiving reports from the garrison about any damage to the fort, the number of casualties, and what the British ships were doing. Just before 9:00 a.m., Armistead ordered the storm flag taken down, the same flag that Key had seen “at the twilight’s last gleaming.” By now the flag was hanging limp against the flagpole, heavy from all the rain absorbed by the wool. Following army regulations, at 9:00 a.m. Armistead ordered the garrison flag raised. The garrison’s fife and drums, joined by the musicians of the Maryland militia, played the national air “Yankee Doodle” while the large wool 30’ x 42’ garrison flag was hoisted.

As the flag rose to the top of the flagpole, the sun broke through the clouds, shining onto the flag. Aboard the PRESIDENT, Skinner, Beanes, and Key, watching through a spyglass, saw the large 30’x 42’ flag reflected in the sunlight, waving over the ramparts of Fort McHenry. They were elated that the fort was still held by the Americans.

If you’d like to look into the complete history of before and after the Battle of Baltimore, as well as Francis Scott Key, as well as the history of how his poem became our national anthem, check out

https://www.nps.gov/fomc/learn/historyculture/battle-of-baltimore.htm

The original flag is in the Smithsonian. And it’s 30 x 42 FEET!

Very moving!

How much do you know about it?

Other than the song the orchestras play on July 4th?

This reveals just a few.

I have a really hard time picturing it . . .

There was noting of note down those steps. : (

On our way out, we took the time for a Volunteer-led talk about the battle, which was good and had the added bonus of being able to be held inside the air conditioned conference room rather than standing in the sweltering, oppressive heat, since there were only four of us.

So now we’re done here, and it’s time to head over to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, but neither of us felt up to it. There were three deciding factors – the heat and humidity, the traffic, the parking. To beat the traffic and the parking, Blaine had thought we’d take a ferry from the fort over, but tickets were $20 – – EACH! ONE WAY! We just didn’t feel like it.

So we went home, and I threw together Tropical Shrimp Salsa and homemade garlic bread. Yum!! (recipe below)

And we received pictures from home! Blaine’s sister and brother-in-law are visiting from Florida. Sure wish we were there!

Our younger son, Kyle, Blaine’s sister Sandy, Harper, Kade, Shena and Cooper

TROPICAL SHRIMP SALSA

20 medium shrimp, peeled and deveined

3 canned pineapple rings

½ red onion, sliced in round (so it can be grilled)

½ large red pepper, left whole

Olive oil

1 jalapeno pepper, minced

2 T. cilantro, chopped

2 T. lime juice

Tortilla chips or garlic bread

Brush the first 4 ingredients with olive oil. Grill on medium-high heat, turning until shrimp is cooked, about 5 minutes. Chop and toss with the next 3 ingredients.

Serve with chips or garlic bread.

Serves 2 for dinner

HINT: I didn’t chop the shrimp since it was for dinner and not an appetizer.