Before I begin to tell you about Madame Marie Tussaud, I want to warn you that due to the macabre nature of her life, some of what you are about to read and see is pretty gruesome. If you have a weak constitution, you may wish to skip this one.

What a remarkable and very dark life this woman lived. She lived with royalty, was thrown into prison, released and forced to create death masks of her friends and searched through severed heads at the cemetery to keep her business afloat. Marie was an artist whose art reflected the gruesomeness and beauty of death. She made it through the French Revolution, went to England and turned her business from a small traveling show into a world empire and became one of the 19th century’s most successful business women. A contemporary of P.T. Barnum in show business, she was a woman way ahead of her time.

Marie Grotsholtz was born near the Germany-France border in Strasburg, France on December 1, 1761. Her parents were Anne Marie and a father she never met. He was a German soldier whose face was horribly disfigured in war. His lower jaw was shot away and replaced by a silver plate. He died two months before Marie was born. Her mother moved to Berne, Switzerland to be near family. When Marie was 6 years old, she and her mother went to Paris to stay with Anne’s brother, a doctor named Philippe Curtius, who besides being a skilled physician, ran a museum of waxwork heads and busts that were also used for medical studies.

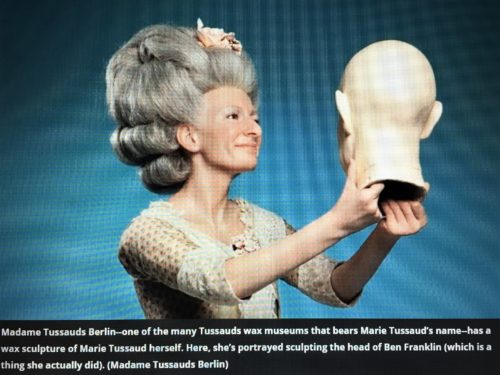

Anne kept the house and Marie became an apprentice for Dr. Curtius, and he considered her a prize pupil from a young age. Because of his skill as a physician, Marie grew up with, met and mingled with many of Paris’ prominent citizens of the day. Her first sculpture, at age 16, was a likeness of Francois Voltaire (an historian and philosopher who was very well known) just two months before Voltaire died. Shortly after Voltaire, she also did Benjamin Franklin who was the American Ambassador to France at the time, followed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (a Swiss-born philosopher, writer and political theorist whose treatises and novels inspired the leaders of the French Revolution), Honore’-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (known as Mirabeau – no wonder considering the length of that name! He’s quite a colorful character if you’ve a mind to read his biography! Simply, for the purposes of this blog, he was a French politician and orator), Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (How’d ya like to have to sign that name?? He was a Frenchman who fought in the American Revolutionary War and named his first son after George Washington. He also helped shape France’s political structure before and after the French Revolution.) and other prominent people.

Francois Voltaire

Benjamin Franklin

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Honore’-Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau

Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette

At age 19, Marie moved to Versailles, France and lived with the Royals until she was 28, working as the art teacher to King Louis XVI’s sister, Madame Elizabeth where she met many of the Royal family members.

In 1789, Dr. Curtius became aware of the rumblings of the French Revolution and he went to Versailles to bring Marie back home to Paris because the Revolution was set to end the reign of the corrupt and selfish royalty. The country was in dire financial straits due to the expenses of their involvement in the American Revolution and extravagant spending by the King. There was no money and in addition, there had been 20 years of poor harvests, draught, cattle disease and skyrocketing bread prices which caused unrest among the peasants and urban poor. Many of them expressed their resentment toward the Royals (by rioting, looting and striking) who imposed heavy taxes, but kept the money for themselves. During this 10-year revolution (aka The Reign of Terror), thousands of people were officially tried and executed by guillotine. Countless others died in prison without a trial. 1799 brought an end to the Revolution and ushered in the Napoleonic era, during which France would dominate much of continental Europe.

It was during all this, that Marie plied her trade – initially by force, and then by choice. At some point during 1793, she was targeted as a royalist sympathizer, imprisoned along with her mother for three months and sentenced to die by guillotine; adding her head to the estimated 16,000 (in Paris) and 40,000 (country-wide) others during The Reign of Terror. However, once it was learned that she was a skilled wax modeler, she was spared and instead was forced by the Revolutionary Government to make death masks of some of the most famous guillotine victims, including King Louis XVI and his Queen, Marie Antoinette in 1793.

King Louis XVI

(I think by the time he died, he was a much larger man.)

Painting of Marie Antoinettte

A waxwork of Marie molding the death mask of Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette’s mold from her death mask

1793

She was also required to make death masks of countless others the Government had a desire to preserve. The masks were put on poles and paraded in a ‘victory march’ around town. One of the most difficult masks she was forced to make was of Marie Thérèse Louise of Savoy, the Princess de Lamballe, whom Marie regarded as one of the sweetest and kindest people she knew. The Princess was taken from prison, horribly abused and murdered. The murderers then took her severed head to Marie and stood over her while she was forced to make a wax cast of it.

Marie Thérèse Louise of Savoy, the Princess de Laballe

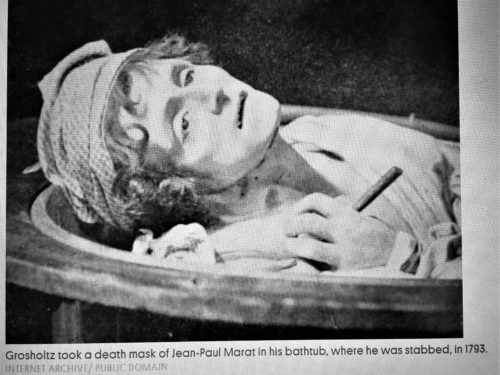

On July 13, 1793 when radical journalist, Jean-Paul Marat was murdered in his bathtub, policemen escorted Marie to the scene of the crime to take a mold of his still warm head.

Jean-Paul Marat portrait

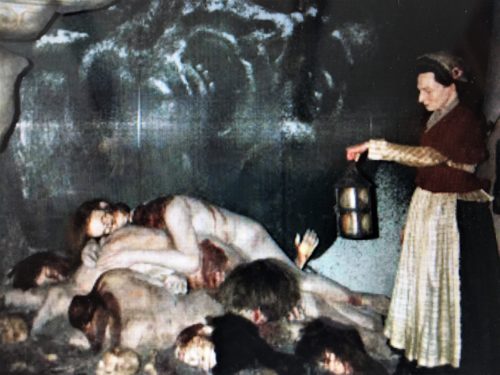

Four days later, she was in the cemetery making a cast of the face of his murderer, Charlotte Corday. This was on her own time and for her business. She visited the local cemetery every evening and sorted through the daily deposits of heads and bodies looking for those that might have historical significance and she hoped would bring in the most interest to her now floundering business.

Charlotte Corday painting

Waxwork display of Marie scouring the cemetery. Ewww!

Most of these original wax sculptures were destroyed in various fires and bombings, but a number of original plaster casts still exist, allowing new masks to be created.

When Dr. Curtius went off to war, Marie was left to run the business on her own. She was about 30 years old. The sculptures were typically wax heads that were mounted on costumed mannequin bodies and became “real-time” political commentary for Parisians.

But people were fleeing Paris and the government expected everyone to support the war effort by handing over all their “nonessential” wealth. No one wanted to be caught spending money on entertainment. Besides, they didn’t need to pay to see wax heads, when the real ones were abundant in the public square every single day.

Marie was forced to take out a loan in an effort to keep the family from losing everything.

Before we move on with Marie, consider how these death masks were made, and their importance to history:

Death masks are an important artifact throughout history. Without photography, they were the only way of perfectly preserving the face of the deceased. The creation of the death mask is a very ancient tradition, and part of many culture’s funerary rites. In Ancient Rome, wax masks of the family ancestors were worn by someone who closely resembled the deceased and followed the newly dead in the funerary procession. In the 19th century, they were considered more of a souvenir and curio for the infamous dead like Jesse James and Butch Cassidy. In order to create these masks, wax or plaster is covered over the face of the dead until it solidifies. From this cast, a mask is made from a variety of substances. Often masks were made of royalty or eminent figures in history, such as Henry VIII or William Shakespeare. In more recent history, Alfred Hitchcock and Benjamin Franklin. It was also used to preserve the faces of the unknown, if an individual died without identification, a plaster mask would preserve their final appearance and allow a better chance of identification than the decaying remains. An interesting fact is that the Resuscitation Annie CPR mannequins used by the Red Cross and other organizations is based on a death mask of an unidentified women who was reportedly drowned in France in the late 1880’s.

In order to create a death mask, there was a specific process: First, the deceased’s hair and eyebrows were covered with clay or oil so that the plaster would not stick to it. Next, plaster was ladled over the head of the individual. Sometimes this meant propping them up into a sitting position as seen in the picture or carefully doing it lying down. Next a thread was placed from the bottom of the chin to the top of the forehead in this thinner plaster. Fourth, thicker plaster was added and the string was removed to create a mask in two halves for easier removal. Once hard, the mold was removed, and then placed back together. Before a mask could be made, the plaster cast was cleaned and then filled with modeling clay or new plaster to make the mask. Finally, the masks were often painted or decorated, sometimes made into more elaborate metal masks, or just left plain and displayed (Beccia 2008).

Death masks are interesting because they preserve both a likeness of the deceased but also a dissimilarity. In death the face loses its movement and emotion that made it the individual, but it does preserve some of the unique traits that define the individual. It can preserve how the last years of a person’s life treated them, such as the gaunt face of Abraham Lincoln at death showing the stress of the war. As Jays writes on the subject, “Death doesn’t lie, so death masks – a cast of the face in wax or plaster, taken just hours after breath has gone – promise truthful representations of the departed. In an era before photography, these masks give us each beauty and blemish, a living presence in unchanging material”.

When Marie was 33, the man substantially responsible for the Reign of Terror against anyone he considered a royal sympathizer (or who just disagreed with him), was himself finally imprisoned. On July 28, 1794, Maximilien de Robespierre met with the same fate as the thousands he’d ordered executed and was guillotined. His head was dumped in the cemetery, where Marie found it and took a cast of it – possibly happily, since he was the one responsible for the torture and death of so many of her friends, and almost herself and her mother.

Wax work of Maximilien de Robespierre

That same year (1794), Dr. Curtius died and left his property, including his collection of wax figures to Marie.

The following year, in 1795, she married François Tussaud, an engineer. Their first child, a daughter, died, but they had two sons, Joseph and François who grew up to run the wax business with their mother. Her husband turned out to be a lazy spendthrift.

In 1802 at 41 years old, she was invited to take her waxworks to Great Britain, so she packed up her exhibits and her four-year-old son, left her younger son with her mother and aunt and headed to England. Her younger son joined them later, but she never saw her husband again.

Portrait of Marie as she looked at age 42, by her son John.

She spoke no English, but she went on to become a household name as she spent the next thirty or so years touring around England, Scotland and Ireland. In a time before photographs, her waxworks offered a chance to see “news making” figures like Marie Antoinette or Jean-Paul Marat “in the flesh”.

To begin, her exhibition featured what she knew – the severed heads on mannequin bodies of prominent French Revolutionary figures. For the first time, Britain could actually see the features of the French King and Queen, whose deaths they had mourned. But she soon began updating her collection by adding prominent British people. However, even today her London location showcases the Revolution – including the actual blade from the guillotine that was used in Paris, obtained from executioner, Henri Sanson, himself.

Drawing of The Executioner, Henri Sanson

Her desire to titillate those with the monetary means to attend, directed her choice of new models, so she made in-roads with royalty and also kept up to date with the latest gruesome murders and assassinations, having authenticity on her side. Dioramas were popular at the time, but only Marie could claim that she’d taken her casts from the very individuals she portrayed.

Marie’s career significantly improved when she received a commission from the Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia, the Duchess of York. Apparently, the King’s daughter-in-law hired Marie to create a figure of a little boy for her. It seems her husband had left her for his mistress and the Princess was childless. How sad is that?

Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia, the Duchess of York

As I mentioned earlier, Marie remained on the road for 33 years, visiting 75 main towns and a few smaller ones. Consider this: at that time, travelling even a short distance was arduous. The packing and unpacking alone, not counting the travel time and model and costume making would have been near impossible for a young man, but Marie was already middle-aged, with a young child, knowing no one and speaking not a word of English when she began!

Having a talent for show business, she knew that the public would go nuts for two things – royalty and horror shows (the more things change, the more they stay the same! 😊).

So at 74 years old, she finally settled down in London in 1835, on the corner of Baker Street and Portman Square, where because of her popularity, she not only modeled Europe’s elite, but purchased King George IV’s coronation robes and Napoleon’s own carriage. The Duke of Wellington was a regular visitor, admiring the effigies of himself and Napoleon.

Portrait of King George IV in his coronation robes

Napoleon’s Carriage

And when Queen Victoria was crowned in 1837, Madame Tussauds created an elaborate display of the scene. Then in 1840, another scene was created. This one showed Albert sliding the wedding ring on the Queen’s finger. Marie was given permission to exactly replicate the Queen’s wedding gown at a cost of 1,000 pounds. At roughly $125,000 dollars today, it was a small fortune for Marie to shell out. After that, the royalty displays continued, even adding Prince Harry and Meghan Markle this year.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s wedding

Portrait of Queen Victoria’s coronation

1838

Waxwork of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation

1953

Waxwork of The Royal Family

Queen Victoria, King George VI (formerly/originally named Prince Albert),and the future Queen Elizabeth.

I don’t know who the other child is.

Waxwork of two-year-old, Princess Elizabeth

1928

Fitting the crown

1955

Flanked by son, Prince Charles and husband, Prince Philip.

Displayed at a music memorabilia auction in 2006.

A new waxwork of the Queen was unveiled in 2012. It was the 22nd one made since 1928.

The New Duke and Duchess of Sussex –

Prince Harry and Her Royal Highness, Meghan.

I think he looks perfect!

I don’t care for hers.

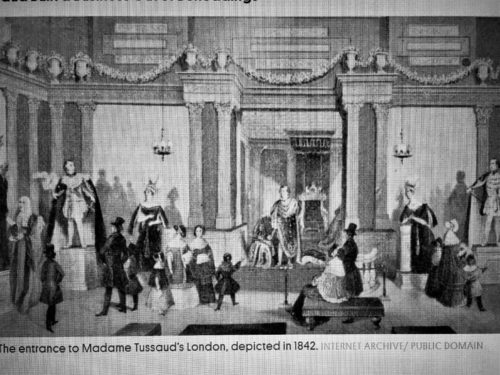

Drawing of the entrance to Madame Tussauds – London

1842

As mentioned earlier, in addition to her “respectable” displays, Marie added a separate room in 1846 which cost an additional fee to view. She called it the “Chamber of Horrors”. In this area were all the decapitated heads, murderers (re-enactments of the murder scenes), mummies and other gruesome displays. It became so well-known that convicted felons about to be executed would often donate their own clothes in order to make their likenesses more accurate.

The Chamber of Horrors paid tribute to the Revolution with a working scale-model guillotine, and the heads of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and Robespierre—the latter grimly squashed in, to reflect the botched suicide attempt in which Robespierre allegedly shot off half of his own jaw.

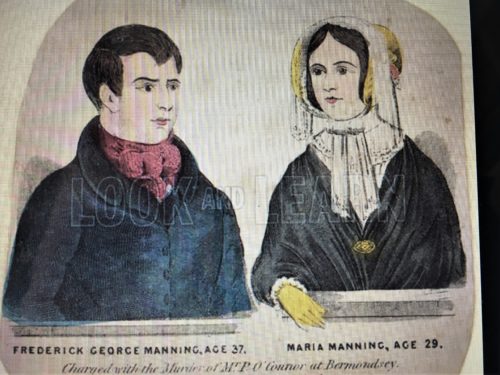

Famous figures in the forbidding salon included an array of British murderers cast from life at their trials, among them James Rush, executed for the triple murder of his landlord and family; and Maria and George Manning, a couple arrested and executed before 50,000 people for the 1849 killing of Maria’s lover.

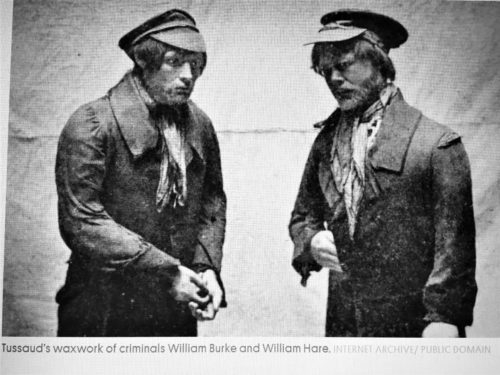

James Rush

The body-snatchers William Burke and William Hare were a popular tableau: when a lodger in Hare’s house died, the men decided to sell his body to willing Edinburgh surgeons faced with a cadaver shortage. It worked out so well (and, unlike grave-robbing, no sweaty digging involved) that Burke and Hare killed 16 more people to repeat the transaction, bringing them in sacks to the hospital for no-questions-asked sale. Marie cast Burke’s head three hours after his execution in 1829. Hare turned King’s evidence and escaped the gallows, but was modeled from life by Tussaud’s sons, who had by that time joined her in business.

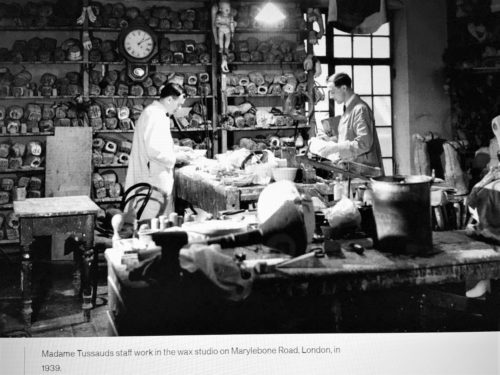

In 1884, Marie’s sons moved the museum to it’s present location on Marylebone Road in London.

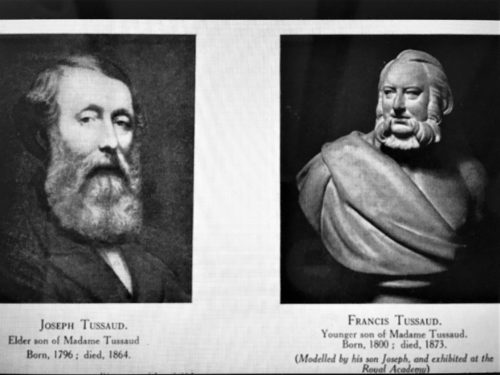

Madame Marie Tussaud’s sons

Advertisement from 1884

In 1925, the museum suffered a fire. Restoration (complete with the addition of a cinema and restaurant) wasn’t completed until 1928. In later years, a direct hit by a German WWII bomb destroyed 352 molds and the cinema, however a few of the original molds and creations still remain.

I don’t know who these people are, but the background shows the damage done to London’s Madame Tussauds following the bombing.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler was immortalized in the Chamber of Horrors, however in 2008 a German man attacked the exhibit and knocked off Hitler’s head. The statue was repaired and replaced and is now carefully guarded.

A drawing of Marie attributed to her son, Francois.

Waxwork of Madame Tussaud

Painting depicts her at the desk collecting money from patrons.

Marie Tussaud died in her home in London on April 15, 1850 at age 89. Her final words were to admonish her sons to never quarrel. Her sons carried on her work, and today, more than 250 years since she began, Madam Tussauds Wax Museum has locations all over the world.

There are currently:

Nine locations in Asia – Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai and Wuhan in China; Tokyo, Japan; Singapore; Bangkok, Thailand; New Delhi, India and Hong Kong. (Did you know that Hong Kong isn’t really China?? I didn’t!)

Eight locations in North America – Hollywood and Los Angeles; Las Vegas; Nashville; New York City; Orlando; San Francisco and Washington D.C.

One in Sydney, Australia

And seven in Europe – Amsterdam, Netherlands; Berlin, Germany; Blackpool, United Kingdom; Istanbul, Turkey; Prague, Czech Republic; Vienna, Austria and of course, their original location in London.

And that’s a wrap! I hope you enjoyed this Special Edition!